The buried remains of the largest Roman villa ever found in Wales have been detected beneath parkland on the south coast, in an “amazing” discovery which archaeologists described as “Port Talbot’s Pompeii”.

The remains were discovered when a team was assembled to investigate the pre-industrial heritage of Margam Park, on the edge of Port Talbot, and they “struck gold” when geophysical surveys revealed the footprint of an unexpectedly large Roman villa complex.

The team, led by Swansea University’s Centre for Heritage Research and Training (CHART), said the villa was “of a scale and level of preservation unmatched across the region”, and that it will offer “unparalleled information about Wales’s national story”.

Project lead Dr Alex Langlands, associate professor and co-director of CHART told The Independent that when the scale of the find became apparent “it was like being transported back to my childhood and the raw enthusiasm I had for archaeology back then”.

When he was sent a screenshot of the geophysical surveys, Dr Langlands said: “I was literally like, ‘oh my god’, I couldn’t believe it… You can immediately recognise, on morphological grounds the shape of a monument and there was no doubt that this was a Roman villa.”

“This is an amazing discovery. We always thought that we’d find something dating to the Romano-British period, but we never dreamed it would be so clearly articulated and with so much potential in terms of what it can tell us about the elusive first millennium AD here in South Wales.”

The location of the site, in an ancient deer park, also means the team expect a high level of preservation, as the area has never been used for agriculture, so has never been ploughed.

Mosaics, paved floors, painted wall plasters, underfloor heating systems and even “high status sculptures” are among what they might expect to find as the site is explored in future.

“It’s a place to dine, a place to entertain, a place to project your wealth and your power. It would almost certainly have had dignitaries from all over South Wales if not Britannia, visiting it and knowing about it,” Dr Langlands said.

“It has the capacity to really change the way we think about Roman Britain, and certainly Roman Wales and what was going on here in the late third and into the fourth centuries,” he added.

While there remain many questions about the use of the building and why it fell into disrepair, Dr Langlands said: “One thing can be concluded, Margam, a place that may even have lent its name to the historic region of Glamorgan, is one of the most important centres of power in Wales, with its geographical location placing it firmly at the gateway between the rugged upland terrain of western Wales and the fertile Vale to the east.”

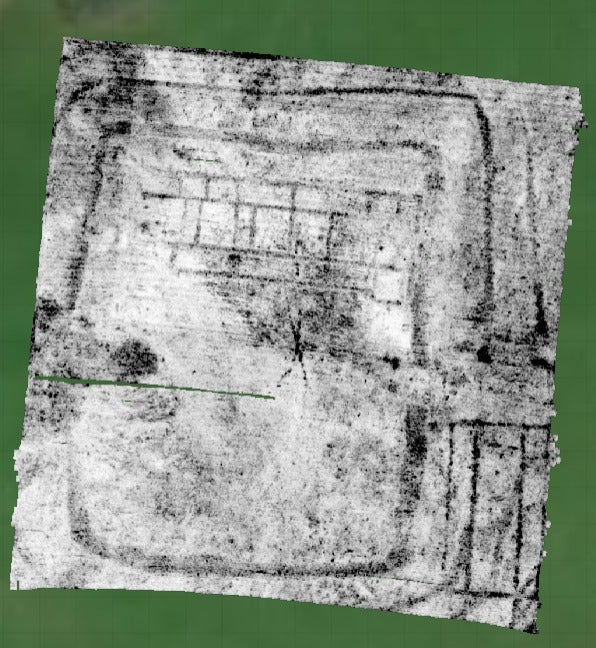

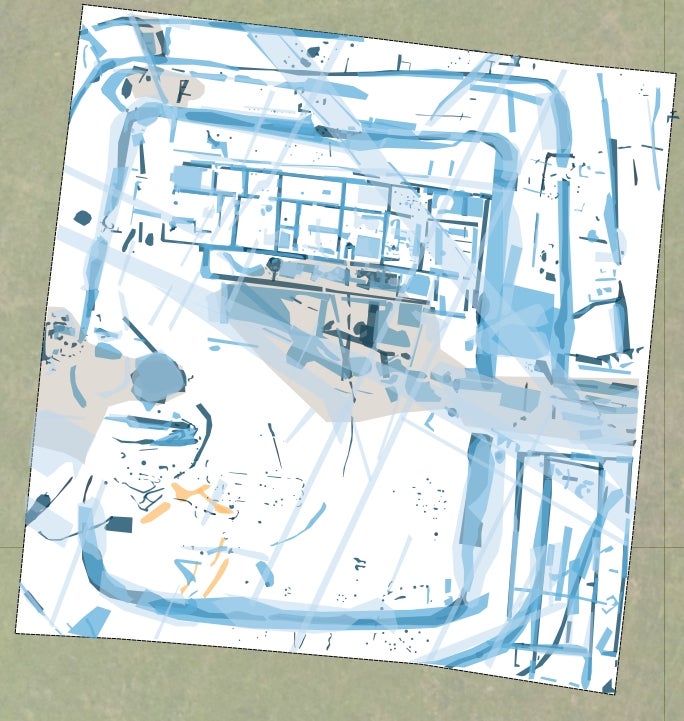

Christian Bird, technical director at Terradat, which carried out the geophysical surveys, said: “The surveys went exceptionally well, and the high-resolution magnetometry and GPR data are remarkably clear, identifying and mapping in 3D the villa structure, surrounding ditches and wider layout of the site.”

The villa sits within a 43×55-metre “defended enclosure”, which the team suggested could be the remains of an earlier Iron Age defended settlement, or that it could reflect instability in the late-Roman world and the need to defend against external aggression from both east and west.

There is also “a substantial aisled building” to the south east, which they said was likely either a large agricultural storage building or a structure related to the later history of the site, “possibly a meeting hall for post-Roman leaders and their followers”.

The original purpose of the project was to invigorate local interest in the rich history already recognised at the site, which is the home of Margam Abbey – a cistercian monastery.

The collaborative project was funded by Neath Port Talbot Council and also involved Margam Abbey Church, and has already “brought together communities, pupils, students, volunteers and SMEs from across the region”, Swansea University said.

Dr Langlands said: “We set the project up to engage locals, community members, volunteers, we’ve had over 350 primary school kids on site. We’ve looked at past excavations. We wanted to capture the power of heritage to change the narrative. These are tricky times at the moment – especially for Port Talbot. So what other stories can we tell round here?”

Cllr Cen Phillips, from Neath Port Talbot Council said: “Heritage is a key asset for Neath Port Talbot and this spectacular find underlines why we as a council set up our Heritage, Culture, Tourism and Events Fund using SPF [shared prosperity fund] funding from the UK Government.

“Our Heritage strategy recognises its power to connect our communities, celebrate our shared identity, and inspire future generations. By valuing and protecting this heritage, we strengthen local pride, attract visitors, and create opportunities for learning and growth. I am extremely excited to find out more from this untold chapter in Margam Park’s long story.”