Forty years ago, 15 years into Queen’s bombastic career, Freddie Mercury released his debut solo album, Mr Bad Guy. “Personally, I think he was trying to make his own version of Thriller,” says Justin Shirley-Smith, Queen’s long-time sound engineer. “Along the same lines stylistically, and certainly he would have wanted it to be as successful. It comes a couple of years after, and looking at the covers, I get the sense there’s an echo there, that expression and angle of the face.”

It was not as successful as Thriller – what is? – peaking at number six in the UK album chart and selling around 100,000 copies, some way behind the millions he was used to shifting with Queen. But four decades on, Mr Bad Guy is a timestamp of an intriguing period of Mercury’s life, and indeed a much-debated footnote in the career arc of Queen themselves.

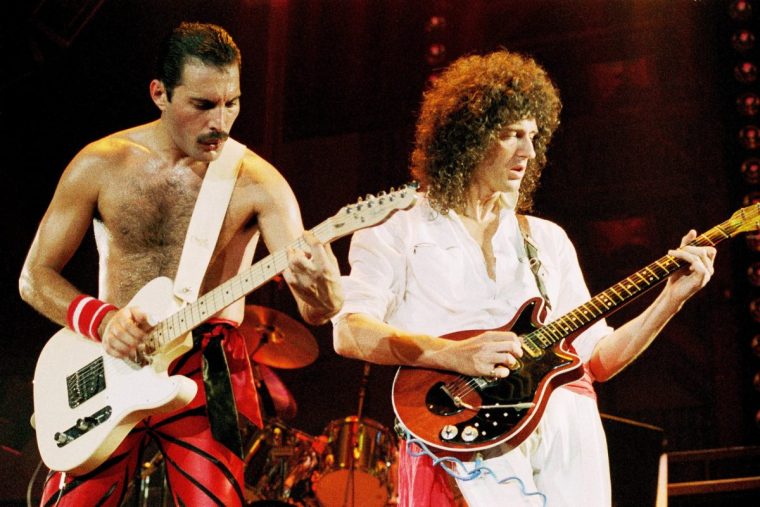

Recorded in Munich, his home away from home, between Queen projects and released just three months before Mercury stole the show at Live Aid 1985, Mr Bad Guy is the sound of Mercury freeing himself from the constraints and expectation of Queen. A new 40th-anniversary vinyl mix of the album, overseen by Shirley-Smith and Joshua J Macrae, restores and updates the recordings.

“He wanted to do something different that he might not have been able to accomplish with Queen,” says Fred Mandel, a Canadian session musician who toured and recorded with Queen and Elton John, and played on Mr Bad Guy. “Which was his own compositions in a different genre.” After the success of Queen’s 1982 megahit “Another One Bites the Dust”, Mercury wanted Queen to explore a more disco-indebted sound. “But some of the other guys wanted to go back to a more rock sound,” Mandel says.

Mercury had already dabbled in a dancier solo sound for 1984 single “Love Kills”, written with disco legend Giorgio Moroder for a restoration of the 1927 classic silent movie Metropolis, and wanted to go further. “I don’t think he did it with the intention of leaving the group. I think he did it with the intention of just creatively exercising his muscles.”

Both Mandel and Shirley-Smith knew Mercury well. Mandel first met him when he joined Queen as touring musician in 1982 (he later played on Brian May’s 1983 Starfleet mini-album and on Queen’s 1984 album The Works). “He’s a lot more reserved offstage than the persona that I think some people associate with him,” Mandel says. “Freddie could be almost actor-ish sometimes. But he was a very bright guy, and I think he had a sense of where that was applicable, his personality. But to me, he was a very nice, very honourable guy.”

In 1984, when he was 18, Shirley-Smith got a job at Queen’s commercial recording studio in Montreux, Switzerland; he engineered Queen albums until 1995’s post-Freddie swansong Made in Heaven. “He said the studio should be in the lake rather than by the lake, because he found it boring, basically, in terms of his late-70s, early-80s lifestyle,” Shirley-Smith says of Mercury’s notorious partying. “But Freddie was always just very funny. Everyone was laughing around him, especially him and Roger [Taylor] together.”

They are both well placed to say that perhaps some things we understand from this time in Mercury’s life aren’t strictly accurate. If you’ve seen the 2018 Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody (starring Rami Malek in the main role), you might be under the impression that the 18 months before Live Aid were a tough period for Mercury. Partying to excess in Munich where he lived on and off between 1979 and 1985, Mercury was said to be lonely and completely alienated from his Queen bandmates. Mr Bad Guy seemed to suggest as much. The sleeve notes to the original record read: “This album is dedicated to my cat Jerry – also Tom, Oscar and Tiffany, and all the cat lovers across the universe – screw everybody else!”

But the distance from his Queen bandmates is exaggerated, Shirley-Smith says. “They had different interests in what they did in their spare time, but they were carrying on [as a band] pretty normally,” he says, noting that while work began on Mr Bad Guy in early 1983, Queen had made 1984 album The Works and performed at Rock in Rio festival in Brazil in January 1985. “The movie makes a lot of them being estranged,” Shirley-Smith says. “But I don’t think it was extreme as that.” “No matter what the press thought, they were like the Four Musketeers,” Mandel says. “They might have had arguments with one another, but they were relatively minor.”

But aside from a hailstorm in Munich one night – “It destroyed a lot of cars in the parking lot; one of Freddie’s cars got pretty heavily damaged” – Mandel says recording was plain sailing. There was no sign of Mercury’s out-of-control hedonism, nor did he cut an unhappy, isolated figure.

“Not when I was there,” says Mandel. “I didn’t get that impression at all. I mean, yes, there are elements of that in the recording,” he says of songs like “Living on My Own”, about the loneliness of touring. “But he was the same as I ever knew him. We were joking around. We went out to dinner in Munich one night, a traditional kind of German restaurant, and we hung out for a few days, and he seemed fine to me.”

Mandel says the week he recorded with Mercury and co-producer Reinhold Mack, who had produced all of Queen’s 80s albums, Mercury was focused and businesslike – and as good as ever in the studio. “You don’t have to autotune Freddie,” Mandel says. “Just let him go.” Mandel says it was a case of: “Which vocal do you use – better or best?”

Creatively, Mercury was overflowing with ideas. Among moving ballads – the epic “Made in Heaven” and “Love Me Like There’s No Tomorrow”, about his affair with the Austrian actress Barbara Valentin – there were complex and inventive arrangements (the theatre pop of “Man Made Paradise”) and new sounds in the disco power ballad of “I Was Born to Love You”, giddy synths of “Let’s Get It On” and reggae track “My Love is Dangerous” (“who wants their love to be safe?” Mercury quipped at the time).

The title track employs the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra: surprisingly given Queen’s reputation for grandiosity, it was actually the first time Mercury had ever recorded with an orchestra. “That’s because he did have a full orchestra,” Mandel says, “and his name was Brian.”

Mr Bad Guy knowingly pokes fun at his reputation for debauchery and flamboyance. “I am a man of extremes,” Mercury said at the time. Did either ever see the Mr Bad Guy side of him? “I mean, obviously he was naughty. Everyone knows that, don’t they?” Shirley-Smith says. “In the traditional sense of the word bad, my experience was that he was very generous in every way.”

“I didn’t see any real diva moments with him,” Mandel says. “I’d see people get irritated on the road. But I never saw him throwing stuff around the dressing room.”

Mr Bad Guy was released on 6 April 1985; after only one of the four singles reached the top 40 – “I Was Born to Love You” at number 11 – Shirley-Smith says Mercury quickly moved on. “He got slightly bored of this album, because he spent a lot of time at the beginning working on the songs,” Shirley-Smith says. “I think there was a rush at the end to finish it. I’ve been in the studio with Freddie – he was impatient. The songs are really great, and a lot of the vocal performances are fantastic, but in terms of production and mix, I think it left a bit to be desired.”

He stresses this is not a criticism of Reinhold Mack. “Mack is a genius and his work on this album, getting Freddie’s vocals the way they are and keeping the fun intact, was a real achievement. I think he was up against it, quite frankly, in many ways.” There were “technical problems with drum machines, and also the sync between the tapes. Now we can correct things like that and give it a bit more punch and weight.”

Shirley-Smith continued to work with Mercury on Queen albums until Mercury’s death from an Aids-related illness aged 45 in November 1991. Even as ill health took its toll, the frontman was determined to work. “Yes, he was definitely keen just to carry on.” In May 1991, Shirley-Smith helped record Mercury’s last recording, “Mother Love”, and recalls how the two of them worked in the studio alone on vocals for “A Winter’s Tale” a few days earlier.

“It was amazing, really,” Shirley-Smith says. “It’s hard to describe, because it sounds like it should be very sad, but he always made light of everything. He had a walking stick but he was standing to sing in the control room, which is unusual. But he preferred to be right there with you and have eye-to-eye contact. He amazingly seemed to be enjoying himself, even though he was struggling to hit some notes.”

Given it was relatively overlooked, Mr Bad Guy had ripples of a legacy. In 1993, “Living on My Own” became a huge number one hit after a remix by No More Brothers; in 1995, “Made in Heaven” was re-recorded by Queen for their posthumous 1995 album of the same name, their first and only album since Mercury’s passing.

And piano ballad “There Must Be More to Life Than This” – originally written for Hot Space – resurfaced on the 2014 compilation Queen Forever in a version with Michael Jackson on vocals. It was one of three tracks recorded during the infamous, ill-fated collaboration between Mercury and Jackson at the latter’s Californian studio in 1983. Personal and creative differences meant the project fell apart. “I only know what people have said: that he went there, but he wasn’t too keen on [Jackson’s] llama in the studio,” Shirley-Smith says.

But it means that, though inevitably overshadowed by Queen, Mr Bad Guy has its place in the Mercury story. “Well, it’s totally unique, isn’t it?” Shirley-Smith says. “Because he did two solo albums, and they’re very different from each other. And hopefully we’ve made it more accessible than it already was.”

‘Mr Bad Guy’ 40th Anniversary Special Edition is out now