The Netherlands has one of the lowest rates of young people not in education, employment or training in Europe

Sir Keir Starmer announced on Monday that the UK Government would look into removing the barriers “holding back the potential” of young people.

“We have to confront the reality that our welfare state is trapping people, not just in poverty, but out of work. Young people in particular, and that is a poverty of ambition,” he said.

Alan Milburn, the former health secretary, is due to deliver a review next summer on the state of NEETs in the UK, individuals typically aged between 16 and 24 who are not in education, employment or training. Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that around 13.4 per cent of those in the age group are in such a position, or about 987,000 people.

As Starmer looks at ways to improve employment rates among British youth, experts have told The i Paper that the Netherlands is a prime example of a country the UK could model itself on.

Young people ‘churn’ between different jobs

Robin Simmons, Chair of the School of Education and the University of Greater Manchester, has carried out extensive work comparing the prevalence of NEETs in the UK with other European countries.

Simmons said encouraging young people into work or education is typically handled by local authorities in the UK, but that the weakened financial state of these bodies has stripped away many of the tools used to handle the issue.

He also pointed at employability providers, which aim to lead such individuals into jobs but vary greatly in quality.

“They force young people into the labour market, often into things that are unsuitable, boring, unrewarding or exploitative and so they bounce back out… They churn between different sites, often with a poor quality of engagement,” he told The i Paper.

Simmons added: “What we found in our research is that these negative experiences in a labour market are a bit like putting your finger in a plug – you don’t want to do it again. So the actual quality of the engagement is really important.”

Quality vocational education

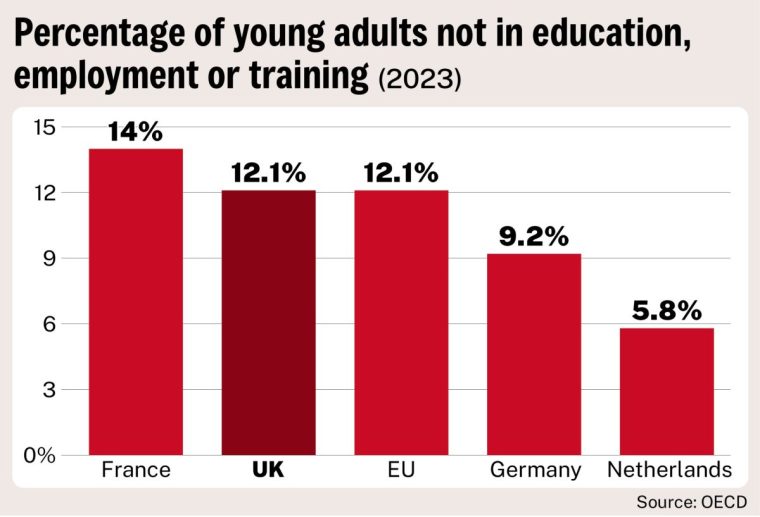

Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said that 12.1 per cent of British young people aged between 15 and 29 in 2023 were not employed or in formal education, mirroring the average in the EU.

However, some countries are doing a much better job, with Germany at 9.2 per cent and the Netherlands showing one of the best rates, at an impressive 5.8 per cent.

Mark Levels, the Dean for Lifelong Development at Maastricht University, said the Netherlands has long been known as a country with one of the lowest rates of NEETs in Europe.

He put this down in part to the high quality of its vocational education and training (VET) system, similar to an apprenticeship scheme in the UK.

Levels told The i Paper: “One of the best aspects of the system is it teaches people marketable skills that are in demand on the labour market. There is a link between firms and the private sector. They co-curate the curriculum to ensure what people learn is what they need to know and master.”

He said the VET system is recognised in the Dutch labour market as a sign of having quality skills in a certain occupational field.

European Commission data states that 90.5 per cent of recent Dutch VET graduates were in employment in 2024, compared to the EU average of 80 per cent for graduates of similar courses. In addition, 94.3 per cent of VET students gained work-based learning experience while studying, with the EU average sitting at 65.2 per cent.

Secondary education in the Netherlands is also compulsory until the age of 16, when some start to receive basic qualifications, depending on whether they chose to pursue a vocational, theory-based or pre-university pathway.

Those who have not received a qualification by the age of 16 are obliged by law to remain in education until the age of 18.

“There is a concerted effort to keep people active and in education,” Levels said. “In the Netherlands, if you don’t have an entry-level qualification for the labour market, they keep you until you are 18 in the education system, so you have to keep on studying. We have people checking that, as early school leavers are a huge factor for NEET status.”

‘I thought the UK had a lot of job opportunities’

Some people have experienced the gulf between the Netherlands and UK first-hand.

Simone, who did not wish to share her second name, grew up in the Netherlands and did an Erasmus year at the Chelsea College of Arts in London, before transferring her degree to the university and finish it in the UK.

She said she worked a variety of freelance and part-time jobs after her degree due to the difficulty in finding a job in her desired career, adding that the lack of professional placements in many UK courses makes finding jobs tricky.

“Back then, I thought the UK had a lot of job opportunities, especially in fashion and the arts, but I learned quickly that’s not always the case,” she told The i Paper. “Without work experience, it’s really difficult in the UK to find a job in what you want to do unless you have connections or parents that can pay for some of your rent and get you free internships.”

Simone is now studying for a master’s degree at the University of Amsterdam, with a fellowship from the Rijksmuseum, allowing her to use a two-year bursary to work at the museum and pursue paid placements in other cities.

“They do this because they want people to have these deeply specific skills, exactly how they want it,” she said. “So they give you this option to enroll into this sort of paid internship in a way from the government… There is this old idea that if you work hard and you have the brains or determination, you can move up.”

How the UK could learn from the Netherlands

Both Levels and Simmons said directly replicating the Dutch system in the UK would be difficult due to core differences in each country’s government structures.

However, Simmons pointed to a previous example in the UK when Gordon Brown was prime minister, called the Future Jobs Fund, introduced in 2009 to address concerns about the effects of rising youth unemployment.

“That was quite good, it was giving employers encouragement to take on young people including graduates… Most importantly, the Future Jobs fund was about good quality jobs,” he said.

The scheme was ultimately scrapped by the Cameron-Clegg coalition government in March 2011, citing high costs, but it created an estimated 105,000-plus jobs between October 2009 and March 2011.

Simmons also said that sandwich courses, degrees which include a year-long placement in a professional setting, could be encouraged in the UK to emulate the successful Dutch model.

Reflecting on her time in the UK, Simone said she feels more emphasis should be placed on incentives to keep people in education for longer.

She said that establishing a framework that supports students to learn up until they finish their qualification can also improve the professional outlook of young people as a whole.

Your next read

“I think the mindset of people is very different in the Netherlands, because if you get supported all the time, it’s really easy to live with an open-minded look at the world and be positive so it’s easier to believe that you will get a job,” she said.

Contrasting it with the UK system, she said it is very smart for the government to push people “because in a way you don’t have an option, this is the only thing you can do, even if you don’t want to… In the UK, the government is not really pushing at all in that sense, so I think that’s something maybe they could learn.”