Ministers have pledged to expand police use of facial recognition in a bid to track down dangerous criminals and are asking people how it should be used to form new laws.

Officials hope that police forces will make more use of facial recognition technology across the country, with the policing minister saying the expansion will “put more criminals behind bars”.

But human rights campaigners called on the government to limit police’s use of facial recognition to serious crimes and the search for missing people.

A 10-week consultation is being launched to gather views on how the technology should be regulated and how to protect people’s privacy. It will also ask people what sort of data they think it is acceptable for police to access, for example, whether officers should have greater access to passport photos in certain circumstances.

The government is also proposing to create a regulator to oversee police use of facial recognition, biometrics and other tools.

Policing minister Sarah Jones described facial recognition as the “biggest breakthrough for catching criminals since DNA matching”, saying that it has already helped catch thousands of criminals.

“We will expand its use so that forces can put more criminals behind bars and tackle crime in their communities,” she said.

According to the Home Office, the Metropolitan Police made 1,300 arrests using facial recognition over the past two years, and found more than 100 registered sex offenders breaching their licence conditions.

But the technology has faced criticism, with the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) describing the Met Police’s policy on use of live facial recognition technology as “unlawful”, earlier this year.

The equalities watchdog said the rules and safeguards around the UK’s biggest police force’s use of the technology “fall short” and could have a “chilling effect” on individuals’ rights when used at protests.

Akiko Hart, director of human rights charity organisation Liberty, welcomed the chance to contribute to the government’s consultation, but added: “It’s disappointing the Home Office is starting a consultation with a pledge to ramp up its use”.

“Police forces have been able to make up their own rules for too long – and just this week we learned these cameras have been used to target children as young as 12. The government must halt the rapid rollout of facial recognition technology and make sure there are safeguards in place”.

Children are included on police watchlists if they are missing, or are wanted for an offence or in connection with a high-risk offence.

Ryan Wain, a senior director at the Tony Blair Institute, hailed live facial recognition as “a straight-up safety boost”. He added: “The rollout must accelerate – incrementalism is the enemy of safety”.

The government’s consultation will be used to form the basis of new laws to govern the technology, which could be expected to be in place in around two years’ time.

Currently, the legal basis for facial recognition use is piecemeal, based on common law, data protection and human rights laws.

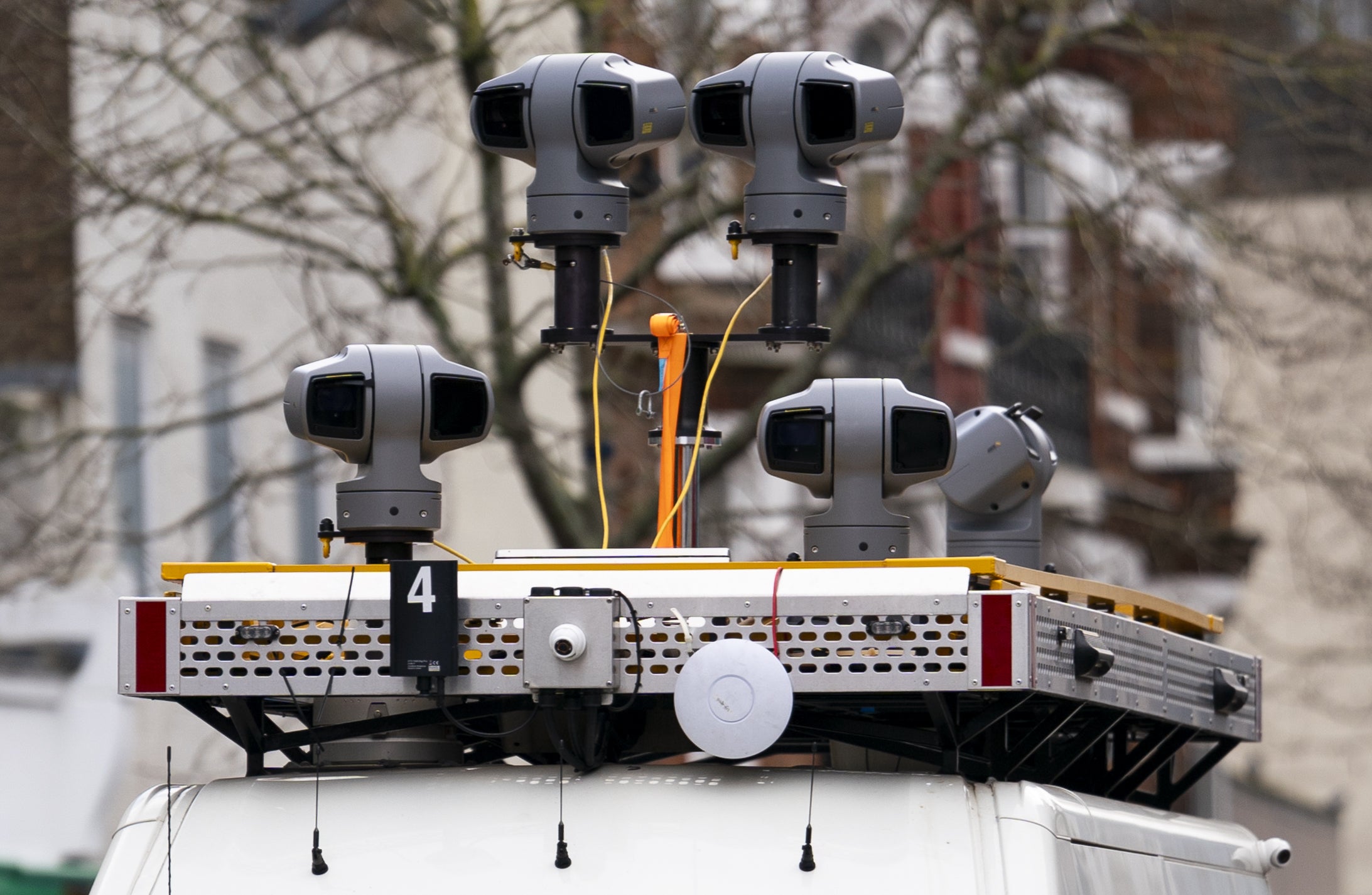

Police use three types of facial recognition: retrospective, used in criminal investigations to search images from crime scenes against images of people taken on arrest; live, using live video footage of people passing by cameras and comparing their images with a list of wanted people; and operator-initiated, a mobile app that allows officers to check someone’s identity without arresting them.

The Home Office funded £12.6 million in facial recognition last year, with £2.8 million spent on national live facial recognition, including mobile vans and fixed location pilots.

Last month, a new fleet of vans was rolled out by Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, Bedfordshire, Surrey, Sussex, Thames Valley and Hampshire police forces in an expanded pilot programme, joining the Met, South Wales Police and Essex Police in their use.

The Home Office also spent £6.6 million this year on evaluating and adopting the technology, including £3.9 million on creating a national facial matching service, which is currently in its testing phase.

It aims to give police a new way to carry out retrospective searching and have another national database of custody images.

It is expected that the new database could hold millions of images, similar to the numbers on the police national database.

Susannah Drury, director of policy and development at charity Missing People, welcomed the consultation.

She said: “Facial recognition technology could help to ensure more missing people are found, protecting people from serious harm.

“However, we need to better understand the ethical implications and what safeguards must be put in place for this technology to be used safely.”