When it became clear to high school theater teacher Gigi Cervantes that she couldn’t ignore a new state law requiring the Ten Commandments to be displayed in her Texas classroom, she felt she had no choice.

She resigned from the job she loved.

“I just was not going to be a part of forcing or imposing religious doctrine onto my students,” she said.

Texas is undertaking the nation’s largest attempt to hang the Ten Commandments in public schools. In the rush to navigate the Republican-led mandate that took effect in September, the rollout has forced some districts to confront hard choices.

Federal courts have ordered more than two dozen of the state’s nearly 1,200 school districts to not hang the posters, including on Tuesday when a judge ruled that the mandate violates First Amendment language guaranteeing religious liberty and forbidding government establishment of religion. Courts have also ruled against similar laws in Arkansas and Louisiana, and the issue is expected to reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

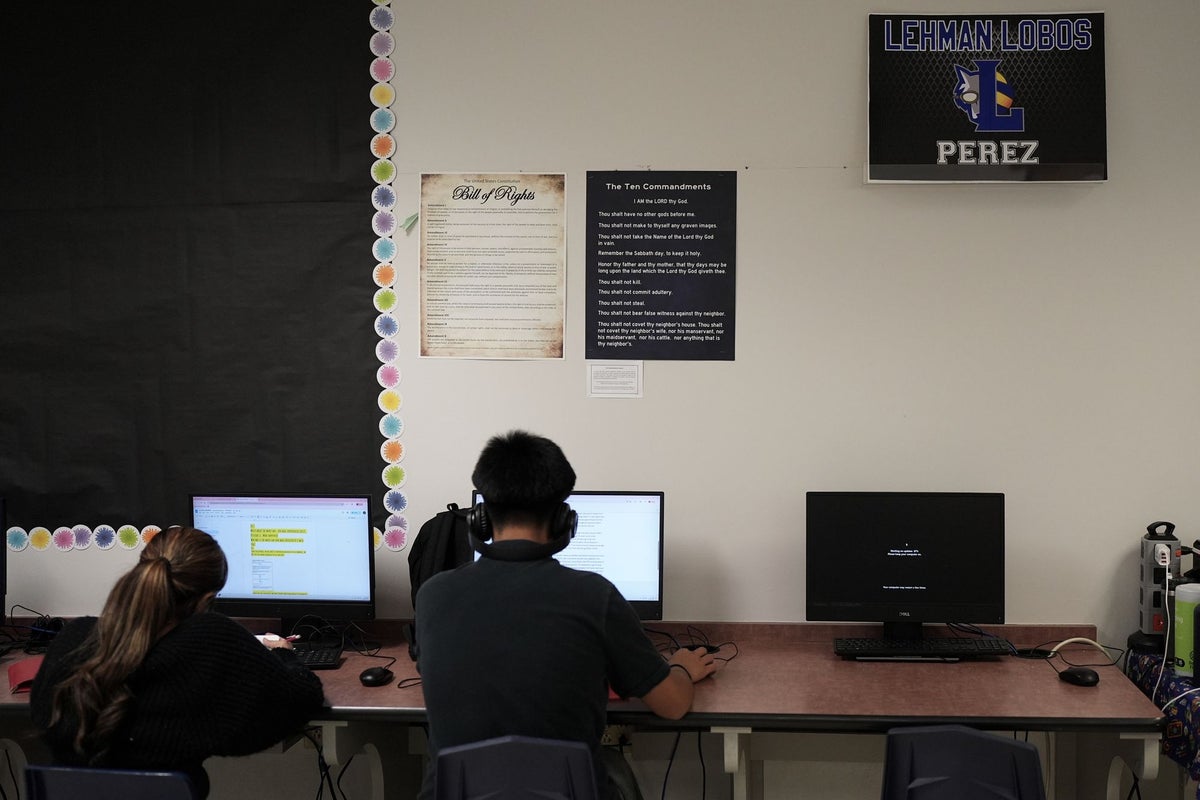

But many Texas classrooms are far along in implementing a law that has animated school board meetings, spun up guidance about what to say when students ask questions, and led to boxes of donated posters being dropped on the doorsteps of campuses statewide.

Some districts didn’t wait: In suburban Dallas, school officials in Frisco spent about $1,800 to print nearly 5,000 posters, even though the law only requires schools to hang the Ten Commandments if the displays are donated. Some schools have no posters to hang.

“I’m not evangelizing,” said eighth grade U.S. history teacher Dustin Parsons, who has a Ten Commandments poster hanging in his classroom in the small city of Whitesboro. He said the display helps him to demonstrate the influence of Christianity on the country’s founding principles.

“I’m doing it more from a history source perspective in how they were building the Constitution,” he said.

School districts face a dilemma

The law says schools must put donated posters “in a conspicuous place” and requires the writing to be a size and typeface that is visible from anywhere in a classroom to a person with “average vision.” The displays must also be 16 inches wide and 20 inches tall (40 centimeters wide and 50 centimeters tall).

South of Austin, the Hays Consolidated Independent School District posted copies of the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights — which includes the First Amendment — alongside the state-required Ten Commandments.

“Districts are in between a rock and a hard place,” said Elizabeth Beeton, a member of the Galveston Independent School District’s school board.

The Galveston school board voted not to post the commandments until the law’s constitutionality is decided in the courts, but then found themselves the target of a state lawsuit. This week, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced lawsuits against two more districts he said were violating the law, though one, the Leander Independent School District said they are displaying donated posters.

Donors see the posters as a moral guide

Texas’ law easily passed the GOP-controlled Legislature and Republicans, including President Donald Trump, have backed posting the Ten Commandments in classrooms.

In suburban Dallas, Lorne Liechty rallied his family to raise money for Ten Commandments posters to donate to the Rockwall Independent School District.

Liechty, an attorney and Rockwall County commissioner, sees the commandments as fundamental to his Christian faith, the country’s legal system and the functioning of society.

“These are just really good guides for human behavior,” Liechty said. “For the life of me, I don’t know why people would object to any of these principles.”

Adriana Bonilla would like to see the posters in her son’s kindergarten near San Antonio.

“It assists with moral foundations and it teaches respect and responsibility,” Bonilla said.

Questions from teachers

Julie Leahy, director of legal services for the nonprofit Texas Classroom Teachers Association, says teachers have been asking about the consequences of refusing to display the commandments and whether they can also display posters with tenets of other religions.

She said teachers also ask for guidance on how to handle students’ questions.

“Generally speaking, the answer is going to be that the teacher should send them back to their family,” Leahy said.

While the Austin high school where Rachel Preston teaches has been barred by a court order from displaying the Ten Commandments, she said she and her colleagues are anxious all the same.

“We’re worried specifically about students who don’t identify as Christian feeling unease at the very least at the presence of this in our classrooms, and struggling as well with how do we contextualize this?” Preston said.

Students debate the posters

When the Ten Commandments were posted last month throughout 16-year-old Madison Creed’s high school in the small East Texas city of Carthage, she said it briefly became the “buzz of the school” as students debated whether the religious doctrine belonged there.

“Everybody had their opinion about it,” Creed said. “I know talking to a lot of my peers and my classmates that a lot of us don’t agree with it but there is the other portion of the school that does.”

Word also came that the high school band director had resigned over the law. Johnnie Cotton wrote on Facebook that he believed “very strongly that politics and religion have no place in the public schools.”

Creed, who plays in the band, said she understood and agreed with Cotton’s stance, and admired that he stood up for his beliefs, even though his resignation two weeks before a big competition was badly timed.

Creed’s mother, Tiffany Meadows, said the posting of the commandments didn’t bother her because she and her children are Christians, but that she was worried about students of other religions.

“These are public schools, these aren’t Christian schools,” Meadows said.

Cervantes, who said she believed complying with the law breached her students’ First Amendment rights, ended her career at the Fort Worth Academy of Fine Arts this fall by leading her students through a production of Molière’s comedy “The Imaginary Invalid.” Her students presented her with a signed cast photograph and many said they respected her point of view.

“I kind of feel like we are living through a time where people who are in positions to be standing up for things are not standing up, not speaking out and there’s a climate of fear,” Cervantes said. “And I don’t want to be any part of that.”