‘Every now and then I feel like a foreigner in my own home and I often wonder where I am,’ one local said

Twenty years ago, born-and-bred Venetian Matteo Secchi would have taken hours to reach Venice’s main train station, Santa Lucia.

“I’d bump into hundreds of people I knew along the way, stopping to greet every one of them,” he recalls.

Fast forward to today, and it takes him just 10 minutes – he knows no one.

“When I was at school, there were 25 kids in my class,” said the 55-year-old. “Now, there are only six of us left. Every now and then I feel like a foreigner in my own home and I often wonder where I am.”

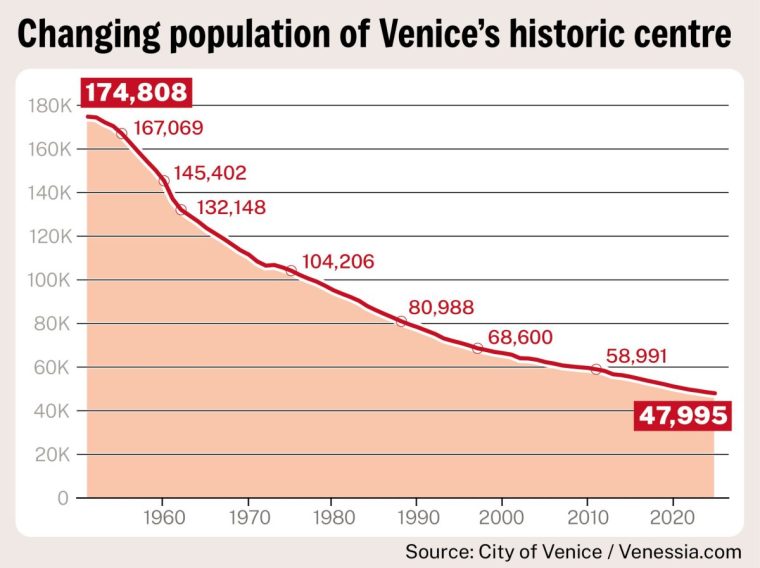

He is not being dramatic. Venice’s residential population has dwindled to its lowest point in history. Only 47,995 residents are left in Venice’s historic centre, according to Venessia.com, a residents’ activist group that has tracked the city’s decline for 25 years through municipal records.

Secchi, the group’s president, has been involved with its work since its inception in 2000, and lives on Venice’s main island.

Since the 1950s, that island has lost more than 120,000 people, with 30,000 residents leaving the city between 1975 and 1995.

Although the decline has slowed since the mid-1990s, the fall has continued. In 1951, the population in the historic centre stood at 175,000 – more than three times more than at present, according to the Venice city council’s statistics office.

“Forty years ago, the park was filled with children playing. Now you maybe see about 10 at maximum. This is the main difference for me – the children,” Secchi said.

“Also the shops are completely different. There used to be bakers, supermarkets…. But now there are just shops for tourists and loads of souvenir shops. There are also loads of sweet shops around and I really don’t understand it,” he adds, recalling a tourist asking him where Captain Candy, a European chain sweet shop, could be found.

“Of all the shops in Venice we have with artisan products, and Venetian snacks, she asked for an international shop meant for children,” he said.

Last year was a big year for post-pandemic tourism levels in Venice – numbers reached 38.8 million, breaking records on overnight stays and surpassing the previous 2019 high – despite the mayor introducing a tax on tourists.

The tariffs – which were officially introduced in 2024 – require day-trippers to pay €5-€10 (£4.30-£8.70) to enter Venice on select days.

While total visitor numbers for 2025 are not yet available, statistics from Veneto’s regional office indicate that overnight stays dropped by around 6 per cent between January and August, despite high-profile events such as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s wedding to Lauren Sánchez in Venice over a three-day event in late June.

“Venice has always had tourists and that’s good for the city, because it brings in money,” said 52-year-old Venetian Alberto Nardi. “I remember tourists from when I was a child. What I don’t remember, however, was overtourism.”

Nardi, a third-generation jeweller, now manages the eponymous family-owned shop that his grandfather founded in 1926 in Saint Mark’s Square. Past clients of theirs included Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly, and members of the Spanish and Belgian royal families.

However he does not believe that tourists themselves are the root cause of Venice’s depopulation.

“Venice’s key issue is that tourism is our main economic driver. We don’t focus on entrepreneurship or innovations and that’s why so many young people are leaving. There are barely any job opportunities outside tourism,” he said.

“We’re a well-known city. There should be more than just renting out your grandmother’s house to tourists or selling souvenirs in a shop.”

Like Secchi, Nardi is involved in a grassroots group aiming to reverse the decline, called Save Venice, where he serves as vice-president. He strongly disagrees with Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro’s recent decision to continue tourist taxes into 2026.

Next year, tourist taxes will apply on 60 scheduled days between 3 April and 26 July, six more days than in 2025.

“Tariffs don’t solve the problem. We aren’t Disneyland. It isn’t the right approach. Everyone must be allowed to visit this city when they want, and it doesn’t help us either,” Nardi added.

Brugnaro, addressing the plunging resident numbers in 2023, said he could not force people to live in Venice, but could create conditions to improve their quality of life. He did not responded to The i Paper‘s request for comment on the latest low figures.

However, Giovanni Martini, an opposition councillor for the Tutta la Città Insieme party, told The i Paper he did not think Brugnaro had done enough.

Martini went as far as to say that quality of life for Venetians had worsened rather than improved, and noted that prioritising tourists had driven the cost of living up for residents.

Your next read

Prices in Venice rose by 2.3 per cent in a year, placing the city fourth in Italy for annual consumer price inflation, according to figures released by The Institute of National Statistics in June.

For residents like Secchi and Nardi, however, the most pressing issue remains the shrinking number of classmates, neighbours and acquaintances.

“We are strong people, as our city was built on mud and salty water,” Secchi said. “I just know if I were a tourist and all the people that once lived in the place had gone, I wouldn’t want to visit it at all.”