Too often musicians’ voices are silenced on politics. But we need them now more than ever

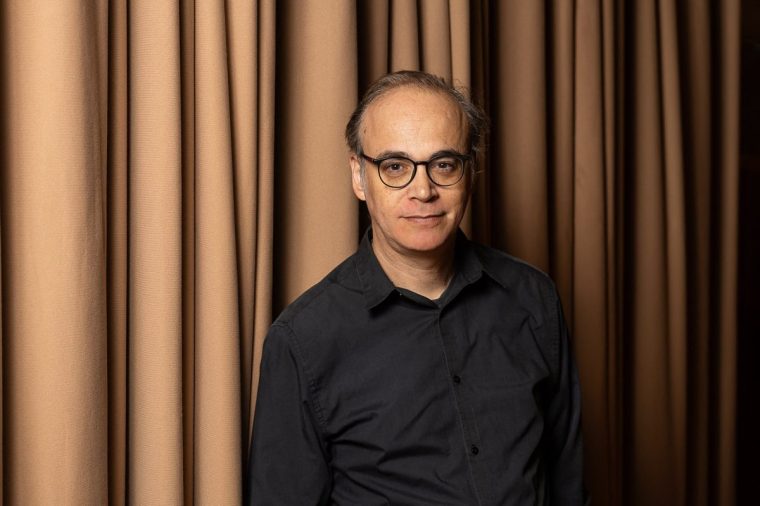

This year at the Proms, the Israeli conductor Ilan Volkov spoke to his audience, voicing impassioned opposition to Israel’s bombardment and starvation of Gaza. He and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra had just performed Brahms’s Symphony No. 2, which was cheered to the rafters. “I come from Israel … I love it, it’s my home, but what’s happening is atrocious and horrific on a scale that’s unimaginable,” Volkov said. One audience member tried to shut him up by yelling obscenities. “You will let me finish and then you can curse me for the rest of your life,” the conductor responded.

His speech went viral on social media and has been viewed around 2 million times on Instagram. It sparked enthusiastic sharing from the pro-Palestine movement and furious trolling and ad hominem attacks from the pro-Israel side.

It’s not surprising if speaking out creates more online rumpus than giving a concert does – but that is one huge reason most musicians do not dare to do it. Not everyone has Volkov’s courage. Since then he has also faced arrest on a protest march to the Gaza border.

My jawbone often ends up bruised upon witnessing the speed at which the public can turn on its beloved artists if they don’t do as they’re told, like good little servants: he is not the first musician to encounter the attitude “Shut up and play!” This directive is levelled at almost any classical performer who uses their platform to voice opinions on world issues. The excuse used to justify muzzling them is that musicians are somehow meant to be above it all. Again and again you hear the snooty remark that “music and politics don’t mix”.

Music may be above it all, but musicians are not. And without musicians, there’s no music (not real music, anyway). Everyone wants music, but even while praising their favourite singers or soloists, many people can’t or won’t acknowledge that musicians are human beings like the rest of us. Besides, the objections typically come from people who disagree with those individuals’ opinions. They are an attempt to silence dissent.

Still, the noisiest controversies have concerned attempts to stifle protest over the situation in Gaza before the recent ceasefire. In August 2024, the Australian pianist Jayson Gillham, in a recital organised by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, played Connor D’Netto’s “Witness”, dedicated to the memories of the numerous journalists killed in the attacks on Gaza.

He told the audience that targeting journalists in a conflict zone is a war crime (the Israeli government has stated journalists are not a target). The orchestra’s management promptly cancelled his next concerto engagement, due a few days later. Gillham sued for discrimination and soon the managing director was obliged to resign. (The orchestra performed in London at the Proms this summer, but faced a demonstration in the auditorium, accused of having silenced artists.)

The derogatory treatment of musicians goes back hundreds of years. In the 18th century, they often had the social status of butlers, waiters or scullery maids. Johann Sebastian Bach was employed by the Leipzig town council, working round the clock as schoolmaster, choirmaster, teacher, organist, conductor and composer. Joseph Haydn, composer of 104 symphonies and mentor to Mozart and Beethoven, spent most of his life as Kapellmeister – head of music, but essentially a liveried servant – in the Esterházy court. Visiting Britain in the 1790s, he was amazed to be treated as a celebrity.

His pupil, Beethoven, sought independence and dignity as an artist, yet relied upon aristocratic patrons while simultaneously rejecting their high-handed behaviour towards him. When Prince Lichnowsky attempted in 1806 to force him to perform to assembled guests who included some French military, the composer stormed out. “There are and have been thousands of princes,” he supposedly said, “but there is only one Beethoven.”

Maybe the tradition of viewing musicians as servants has persisted. Orchestral musicians, lacking individual limelight, get the brunt of it. One of them told me that several decades ago his orchestra played at a royal palace for a glitzy charity event. They were ushered in through a back entrance, confined to an allocated room and provided with a tea urn and a tray of fishpaste sandwiches. And this was relatively good treatment.

Musicians should not be servants except to their art. And when world leadership fails, goes rogue or wimps out, we need others to fill the moral vacuum: people who will stand up for what’s right. Those artists who speak out are sometimes the very people who can lead the way. They’re not “talking politics”, in any case: they’re appealing to our humanity.

The conductor Daniel Barenboim, who has built bridges in the Middle East with many endeavours including his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra that brings together Israeli and Arabic musicians, has often sounded more statesmanlike than the actual statesmen. Now his violinist son, Michael, is taking on that mantle. Volkov, too, is being hailed as a hero by pro-Gaza members of the public who have welcomed his words.

Music shows us what wonders human beings can create. It represents the best of ourselves. That’s why we need it at times when we keep seeing, instead, the worst. So stop telling the people who make music what to think, say and do. It’s time to start listening to them instead.