If Maria Alyokhina hadn’t escaped from Russia disguised as a food courier, she would be in jail right now.

The Pussy Riot activist knows from experience how tough life can be for political prisoners inside Vladimir Putin’s penal colonies. At a remote facility where she was once held in the Ural mountains, temperatures dropped to -35°C in winter, and inmates were forced to work “without hot water, without medicine”.

The goal of these bleak places, she says, is to “erase the personality and teach you only to obey.”

Alyokhina is not really one for obeying. Pussy Riot, her punk band and feminist protest group, shot to worldwide fame in 2012 when she and two bandmates were jailed for performing a song – “Mother of God, drive Putin away” – in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

The show of defiance, in their distinctive bright balaclavas, lasted a mere 40 seconds, but video footage went viral and Alyokhina spent more than a year behind bars for her involvement.

Back then, she says, “I was a student… I was also a young mother.” But with that song, that “punk prayer”, her life changed. She and bandmates were suddenly famous, even addressing the UK Parliament in 2014, and she dedicated herself to opposing the Kremlin. There were huge personal costs.

By the time Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Alyokhina had been trapped in a year-long series of spells either in detention centres or under house arrest – her punishment for supporting Russia’s late opposition leader, Alexei Navalny.

The war finally convinced her that she had to flee. Dressing in the green uniform of a delivery driver, she was driven to Belarus by a friend, where she eventually convinced a border guard to allow her across the border, reaching the safety of Lithuania and the EU.

Now 37, she has been travelling from place to place ever since, staying with friends and allies, while her 18-year-old son Filipp has settled in Iceland. Alyokhina spoke to The i Paper via a video call from Berlin while touring with Pussy Riot.

For both herself and her country, “there is no way back at this point”, Alyokhina says. But she adds: “My experience is a very small drop in the ocean of horror and depressions.” She knows this only too well from visiting Ukraine, where she is fundraising for two hospitals.

Two months ago, a court in Moscow sentenced Alyokhina in absentia to 13 years in jail for criticising the invasion of Ukraine. Four of her Pussy Riot colleagues were handed prison terms, too.

Her sentence was largely symbolic. She has no intention of returning to Russia and its modern-day gulags, which hold more than 2,000 political prisoners according to the United Nations.

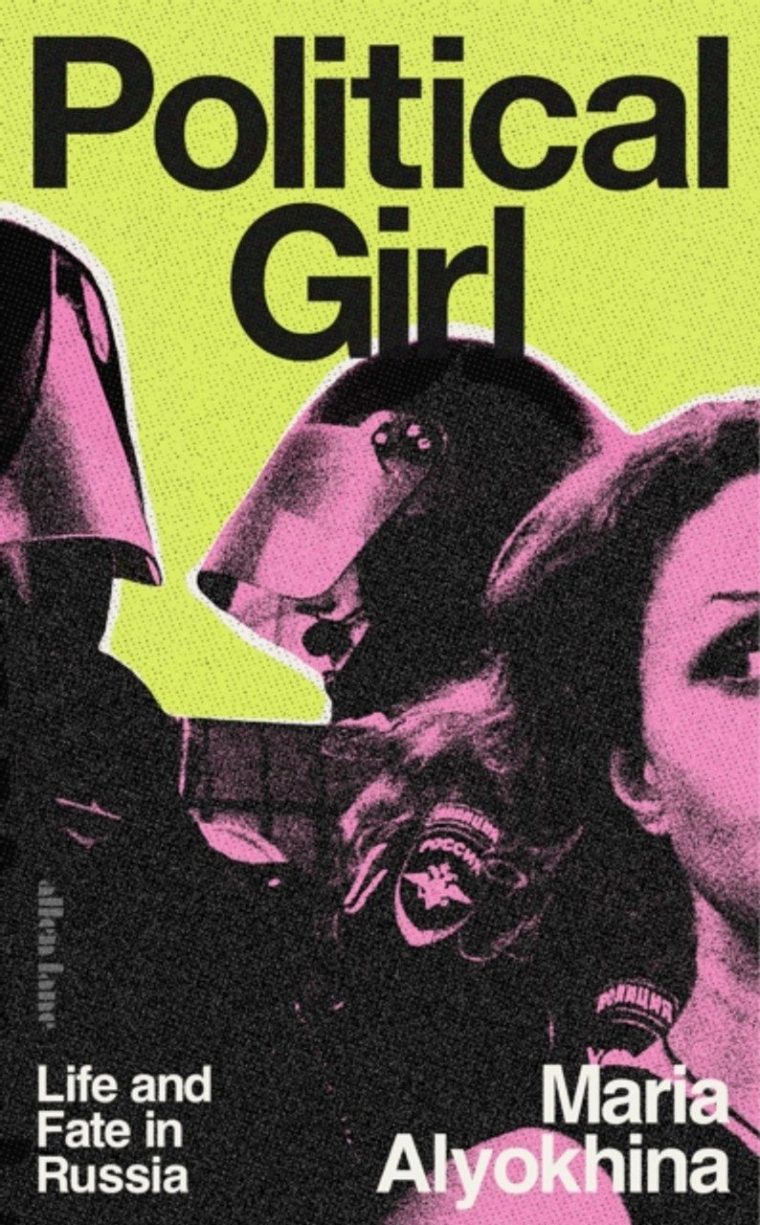

Using her own story to expose conditions for those who dare to oppose Putin was one of the motivations behind her new book, Political Girl, published this week. Its style of short, broken-up passages reflects the disorientating uncertainty of life as an activist in a police state.

Alyokhina also wants people in the West to appreciate how democracies can sleepwalk into becoming dictatorships. In Russia, she says, “it was not like one day we woke up in hell”.

The hardships of Russia’s penal colonies

Recalling her first prosecution in 2012, Alyokhina explains how Putin’s opponents are cut off from the outside world the moment they are arrested. “You are not allowed to call your relatives,” she says. “You are not allowed to talk with your mother or son or whatever.”

During the Pussy Riot investigation and her court case, Alyokhina was held in Moscow’s Pechatniki prison, a pre-trial detention centre for women. After being convicted, she was transported to IK-28, a penal colony 750 miles east of the capital. It is located on the outskirts of Berezniki, a city that has become notorious for its huge sinkholes, caused by old salt mines, which devour homes and businesses.

These facilities are typically former Soviet labour camps, says Alyokhina, and IK-28 “looks like a strange village divided into two parts”.

One zone is made up of barracks. “In the units, there are from 80 to 100 women. They sleep in one room, have two or three toilets… hot water exists in the bath once a week.”

The other area is where the prisoners “work in factories for $3 per month, sewing police uniforms and uniforms for Russian army… If you do not work, you violate the law, they put you to solitary confinement.”

Alyokhina is worried about the fate of her friend Artyom Kamardin, a countercultural poet who has been detained since 2022. Kamardin was arrested for reciting his explicit anti-war work “Kill me, militiaman” beside Moscow’s statue of poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, a spot where dissidents would gather in the 1960s to share anti-Soviet verses.

Alyokhina says police arrived at the apartment he shared with his partner the day after the recital. “They arrested him. They raped him – they recorded that on a video. She was in the next room, they showed her the video and were threatening that they were going to do the same with her.” The officers then allegedly stuck anti-war messages on her face with superglue.

These claims are based on accounts from Karmardin’s lawyer and his wife, Alexandra Popova, who married him while he was in pre-trial detention.

Kamardin was charged with “inciting hatred” and “undermining national security” for reading his poetry and was jailed for seven years. His family were left in the dark over which penal colony he was sent to, and Amnesty International has campaigned for his release, underlining that he requires medical care.

Compared to the harsh conditions of jail, house arrest might sound much easier. In fact, Alyokhina found the mental scars from this form of punishment just as difficult to overcome.

“They turn the house of your childhood into a prison,” she says. “Your own door stops being your own door – you cannot open it and you can’t go out.”

Friends also become wary of speaking and being phone tapped, which succeeds in “increasing your internal paranoia, creating PTSD”.

Alyokhina was moved by news of an 18-year-old musician, Diana Loginova, being arrested for singing an anti-government song in St Petersburg last month, but she salutes anyone brave enough to still protest against Kremlin “assholes” inside Russia, when “everyone understands that it will cost many years in prison or their life”.

‘Don’t be sorry, who started to bomb Ukraine?’

I ask Alyokhina if she is still in touch with all her original bandmates. “With some, yes,” she replies diplomatically. She hasn’t performed with co-founder Nadezhda Tolokonnikova in years but says that’s not due to political arguments. “We lived quite different lives… Different experiences, different adventures.”

No leading Pussy Riot member remains in Russia, and Alyokhina laments how many Russians are now stranded abroad, where “they are invisible and a lot of them are lost”.

One of her friends, Dani Akel Tammam, escaped to Estonia but later joined the Ukrainian army and was killed fighting against his own country. She visited his grave in Kyiv last year.

Alyokhina betrays few emotions in our call. She is slightly bemused when I express my sorrow for the loss of her friend Dani. “Western people say sorry a lot,” she observes. “Don’t be sorry, who started to bomb Ukraine?”

Alyokhina truly admired Navalny, who died last year in the IK-3 penal colony known as Polar Wolf. But she is “not searching for leaders. I’m really punk at this point”, holding more faith in the “power of people”.

Although it would be “really cool” for a political superhero to emerge and “save everyone”, Alyokhina is blunt about the likelihood of this in today’s Russia: “It’s not going to happen.” With a laugh, she adds: “I’m super sorry, as you say.”

With nobody to challenge him internally, she firmly believes that Putin could threaten the rest of the continent. “Putin needs the war, as an essence of the regime. He needs the war and the so-called cult of victory.”

Alyokhina is also alarmed by the rise of populist nationalism throughout the West, and backed the recent “No more Kings” protests in the US against Donald Trump.

Given the US President’s overtures to Putin, as well as his lukewarm support for Ukraine, Alyokhina says “there is actually a danger from both sides” facing Europeans today. She urges the UK and its allies to place further sanctions on Russia and invest more in defence.

The continent should understand, she says, “that if European values mean something, they need to be protected.”

‘Political Girl: Life and Fate in Russia’ by Maria Alyokhina is on sale now (£25, Allen Lane)

@robhastings.bsky.social