Gareth Southgate was not like other England managers. His eight-year tenure began in 2016 and, although no trophies were won, in taking England to two Euros finals (“one moment from immortality,” he sighs); a fourth place slot at one World Cup and a quarter final at another, he out-performed his predecessors. Maybe just as importantly, he was at the vanguard of a new, more compassionate culture in English football.

Southgate saw a bigger picture. He overturned perceptions of what an England manager could be. “It’s not ‘did we win?’ but ‘how did we go about our business?’”, he writes in Dear England, Lessons in Leadership. Nobody seems to have thought more deeply about what the job meant and how a football team and the values he attempted to inculcate – reduced toxicity, increased tolerance, without forsaking the will to win – could help shape the national mood.

Predictably, Southgate’s memoir isn’t a conventional football memoir. It’s about attaining goals, rather than scoring them. Titled after the open letter he wrote before the 2021 Euros and the James Graham play it inspired (which, oddly, Southgate has refused to see; it’s touring until March), Dear England is an impressionistic, roughly chronological affair.

Feelings, lessons and thought processes from his managerial career are linked to chapter-closing bullet points concerning leadership. “What kind of people become great leaders?” asks Southgate. “What life experiences, skills and lessons do they learn along the way?”

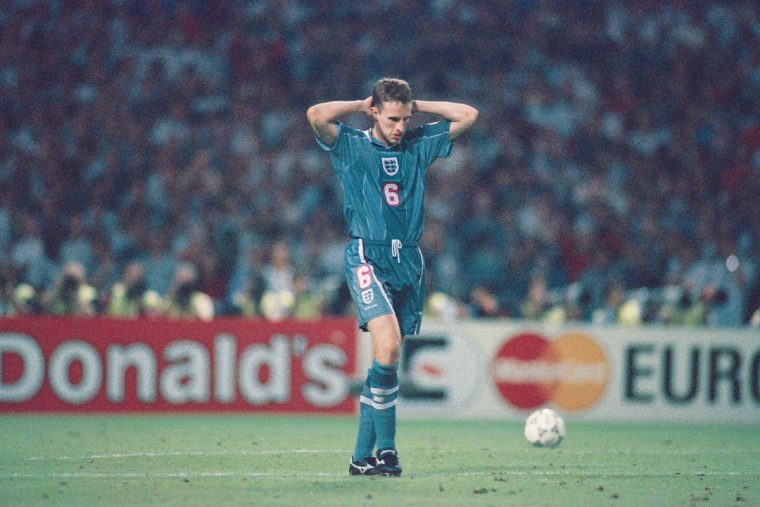

Dear England does include anecdotes and revelations (Southgate was so hands on, he involved himself in the selection of England’s medical staff), but they’re slipped under the counter. Football minutiae mavens looking for a detailed mea culpa regarding the own goal he scored for Blackburn Rovers as an Aston Villa player in February 1999 must look elsewhere, but he does confront his penalty miss which cost England a place in the Euro 1996 Final, although only in terms of a learning experience. “I was inconsolable,” he confesses, until teammate Stuart Pearce gave him the choice between being “permanently floored” or to “get back up and keep going”.

The decision: “The way that moment defined me was within my power to control. Even though people would shout out of vans as I walked down the street, I would build fortitude.” So it proved. That fortitude in the face of adversity and ridicule made Southgate both a better manager and a better person.

Some of the leadership fare feels like an awkward marriage between a self-help screed and corporate HR speak, hence attempts to improve players’ rest via “an information leaflet on sleep hygiene” and a surprise, phone-free, two-day Commandos assault course, where apparently the officers were “unanimous” in lauding future captain Harry Kane’s leadership qualities: “I made a note”. But when Southgate widens the discussion, this middle-class son of Barbara, a Hampshire dinner lady, and Clive, an IBM plant manager, is onto something.

But even Southgate is not above settling scores, notably over the widespread perception that he was too nice to be trophy-winningly successful. “Given I represented England more times as player and manager combined than anyone in the history of English football, I guess I wasn’t too nice to make it,” he sneers, uncharacteristically thin-skinned.

Southgate cites a bungled exit conversation with striker, friend and former teammate Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink as evidence of his early naivety as Middlesbrough’s young boss: “I wasn’t ready”. But by the time he was explaining to England galacticos that they were no longer required, he was a master of the tricky conversation. None took the ending of their England career better than Wayne Rooney: “The humility and dignity Wayne showed me in that moment really stayed with me.”

England were in disarray when Southgate took over. His predecessor Sam Allardyce had lasted just one game before being ousted by a tabloid sting. Before that, England had lost to Iceland under Roy Hodgson, while neither Steve McClaren nor Fabio Capello were of the required standard.

Having risen via England Under-21s, Southgate was steeped in the culture of the Football Association. As such, he wanted to change the system from within: evolution rather than revolution. For him, the so-called “bulldog spirit”, exemplified by Terry Butcher and Paul Ince’s blood-stained England performances of the 80s and 90s, was out of date and counter-productive: “Hadn’t players moved on a bit in this regard?” Instead, he aspired to “take the weight out of the shirt… the sense that we somehow deserved to be winners”, especially for young players, who often shrivelled on the international stage.

Even so, Southgate still needed those who bought into making “ourselves and our nation proud”. As a result, he fostered a sense of belonging (hence the gimmick of inflatable unicorns which enlivened the hitherto disliked water-based training sessions), while showing ruthlessness by jettisoning “high-risk” players, albeit without actually naming any here. And he cheerily admits to having favourites: “Players who could handle the pressure of playing for England, who gave everything for the team, who fitted into the group and who helped us to win big matches.” He softened relationships with the press too, understanding that lack of access to players breeds antagonism.

Like those who came before him, Southgate’s chief bugbear was over-expectation: “The fundamental problem wasn’t with the team’s under-performance, as with the scale of people’s expectations.” The talent pool is shallower than it seems: English clubs may be the world’s best performing and best paying, but Southgate cites weeks where only 66 players eligible for England appear in the Premier League.

Those national team delusions have remained consistent since 1966. When Southgate declared he was aiming for the quarter finals at Russia 2018 – an underestimate, it transpired – both fans and his players were disappointed, but “was acutely aware of setting us up for failure by encouraging unrealistic expectations”.

Perceptions of patriotism have changed and while Southgate’s love for his nation is firm but inclusive, he certainly won’t be found attaching tatty flags to lamp posts in the early hours. Revealingly, if he has one regret about his tenure, it’s bawling out Danny Rose for a needless late sending off in Montenegro, after not noticing Rose had suffered horrendous racial abuse during the game.

The misunderstanding vis-à-vis Rose is a minor blot on the positive legacy he craves, but Southgate’s style of leadership already has a sepia tinge. The Football Association’s pragmatic (or short-sighted) new approach saw his successor, Thomas Tuchel, appointed solely to win the 2026 World Cup, with no obligation to nurture the future, as Southgate so willingly did.

When England formally qualified for that tournament in October with two dead rubbers remaining, there was little celebration across the kingdom. The qualifying campaign has been jaw-droppingly dull; its outcome wearingly predictable and the domestic season-disrupting international breaks – two already this season with another one this month – is almost universally despised by fans and players alike. Yet, as we all know, when the World Cup finals begin on June 11, the national mood will change in an instant, for better and for worse.

Instead, unlike almost all his 15 permanent predecessors, who left managing England bitter or broken, Southgate will be remembered and revered for the hope he brought, but also for emerging seemingly unscathed from a job that “chews you up”. “The prime lesson,” he writes, “is the fine balance between doing everything you can to win and winning at all costs. The first is about excellence. The second risks sacrificing integrity”.

Looking to his future, he notes that few England managers have subsequently found comparable jobs, other than Bobby Robson’s season at Barcelona, but Southgate is only 55. Should Ruben Amorim fail at Manchester United, Southgate may be tempted, but his declaration that “I’m not desperate to manage in the Premier League” has the ring of truth. He adds “never say never” regarding a return to management, but the longer he stays out of football, the more he’s simply saying “never”.

Dear England feels like the testament of a man who has been there and is sufficiently self-aware to understand it’s probably unwise to go there again. You’d hope so, for his sake.

‘Dear England: Lessons in Leadership’ by Gareth Southgate is published by Century, £25