How do Russians genuinely feel about their President? Of his regime? Of his war? Vladimir Putin has ensured it’s very hard to tell.

Citizens can be jailed for up to 15 years for calling his “special military operation” what it actually is: an invasion. Leading political opponents have been poisoned, exiled or assassinated. Few independent journalists remain in the country. And when opinion polls are carried out, they suggest most Russians approve of their government.

That was what drove Jana Bakunina to travel back to the country where she was born and grew up but hasn’t lived for a quarter of a century. “We don’t really hear what ordinary people think,” she says. “What is it that, in their heart of hearts, is driving them to support the regime?”

Jana moved to the UK in 1999 to study. Putin became President the following year. While Russia tried to recover from a decade of economic hardship which followed the fall of communism, she was building a new life in the UK.

“I wasn’t really focusing on the ins and out of Russian politics,” she says. “I was finishing my degree, I was getting my first job, second job.” Her first from Oxford led to a successful career in finance.

It was Putin’s annexation of Crimea and partial invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014 that made Jana wake up to what her country had become, and how many of her own friends and family supported the regime.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, she was “ashamed” and trusted that pro-Putin Russians would finally “see the truth, that the war would be the absolute boundary you cannot cross… That did not happen. In fact, people just doubled down.”

Struggling to comprehend how people could really feel this way, she went back to Russia for a month to interview relatives and old schoolmates, while witnessing for herself what the country had become. Her book The Good Russian, an emotive account of her insights from this rare venture, is being published this week.

Her trip was in autumn 2023, but she remains in touch with those she met. “Two years on,” she tells me, “nothing has changed.”

Meeting pro-Putin friends

Flying via Turkey, Jana returned to her home city of Yekaterinburg, the fourth largest in Russia. It was booming with new apartment blocks, well-kept parks enjoyed by joggers, and busy restaurants. “In the centre, it’s all spotlessly clean,” she says. “There are no beggars on the streets, there are no drunks.”

Early in her trip, Jana was put in her place by friends over dinner. “Russia isn’t suited for democratic rule. We are better off with a tsar,” one told her. Another told her that Putin’s opponents are deluded for not realising “they are in the minority”. A third reflected: “Thanks to Putin, the economy has recovered… Why wouldn’t I trust the Kremlin with foreign policy as well?”

These emerged as common themes in her chats. Take the businessman she caught up with, who is 50 and has three children. He is focused on growing his company, telling himself it will help his country as well as his family. “Russian men are sacrificing their lives so that I can enjoy peace and have a good life,” he told Jana. He doesn’t view Putin as an aberration, because “every Russian ruler has been a bit of a despot”.

She met her childhood friend Katya, who is now the CEO of a major business in Yekaterinburg. She believes that alleged war crimes in Bucha were “fabricated”, because “a Russian wouldn’t loot, rape or kill civilians”. Katya said that “Ukraine is just an unfortunate pawn” in Russia’s efforts “to defend our safety” from Nato, and told Jana that she’d been indoctrinated by the BBC.

These were not isolated examples. She spoke with many others who said similar things. All the names of Jana’s contacts have been changed to protect them.

Those of Jana’s friends who do oppose the war feel powerless.

Her friend Misha, an ophthalmologist, is angered by the “zombiefication” of his parents who he says complain about “Nazis in Ukraine” after watching state-approved TV all day. But Misha and his wife Vera, a manager at a large industrial firm, argue there is nothing they can do to stop the war – so they try to simply shut Putin out of their minds in what they call “inner emigration”.

The couple have focused on supporting their teenage twins and on hobbies such as hiking, picking mushrooms and making jam, while building their dream countryside home on a riverbank by a forest. Vera refuses “to accept any collective responsibility”, with the pair even telling themselves that their taxes help to reconstruct parts of Ukraine occupied by Russia. They know the truth, they just cannot bear to confront it.

Another friend, Sveta, is an accountant funding her daughter’s promising tennis career. “I keep quiet, but inside I’m weeping,” she told Jana. “Even if Putin dies, his successor will be much the same.”

“They’re just so resigned,” says the author. “This is how they live out their days.” She does not expect these individuals to risk their lives by publicly protesting against the might of a dictatorship – which she compares to Nazi Germany – but found the lack of internal defiance “absurd”.

She added: “I am an optimist by nature… But when I was in Russia, I couldn’t see anything positive at all.”

How her parents have been brainwashed

If you want to know what totalitarianism can do to people, the story of Jana’s parents is poignant.

Growing up, her mother and father decorated their flat with Abba and Beatles posters and went on group tours to France, Spain and Italy, even in Soviet years. Her mother was an engineer. Her father, who refused to join the Communist Party, was an academic who later became an entrepreneur, importing everything from clothes to cars. They supported her ambitions to study abroad.

But when Russia annexed Crimea, she was disturbed to hear her parents support what they called a “reunification”. Having originally supported her move abroad to study, her father now berated her for living in the “imperialist West”.

Jana says: “For a decade, we were not able to speak about politics at all. My father would get immediately agitated and accuse me of being brainwashed by the Western media – ‘Come and live here, then you’ll see the truth.’ With my mother, she would just get upset. She would also think I’m brainwashed, she just wouldn’t say it.”

Why had her father changed so vehemently? Partly, she believes it’s down to the resentment of an ageing man seeing his only child enjoy the freedoms he never had. But more fundamentally, “it’s the propaganda that is to blame”.

I ask how her father would sum up his views if he were here in the cafe with us. “He would say that Putin is a remarkable leader who’s standing up for Russia against the imperialists of the UK and the US, that he’s a true patriot, that Ukraine is full of American puppets, and, ‘If I were not in my 70s, I would be now on the front line fighting for Russia.’”

Last year, her father was diagnosed with brain cancer. He pleaded with Jana – an only child – to come back home and live nearby. But she explained to him that the situation is now even more dangerous for Russians who hold Western dual nationalities. If she returned, she would fear being arrested and potentially used as a bargaining chip, to exchange her for Russian prisoners held in Nato countries.

“I said, ‘I’m really sorry, I’m not going to do it, because if I get arrested and put in prison, it’ll probably kill you before cancer does.’ He said, ‘You’re a traitor, you’re not my daughter.’ It was incredibly difficult.”

They eventually reconciled. However, Jana realises it’s unlikely she will ever see her father again, and knows there must be others in the UK facing the same tragedy. She does not ask for sympathy, however. “In the hierarchy of suffering, Russians are far, far behind the Ukrainians.”

Signs that sanctions are failing

Another of the biggest reasons for Putin’s support, Jana believes, is the lack of effect that sanctions have had on Russian society.

Unlike in the West, energy costs have remained low thanks to sovereign supplies of oil and gas. Russians can still holiday in Europe by flying via a non-EU nation.

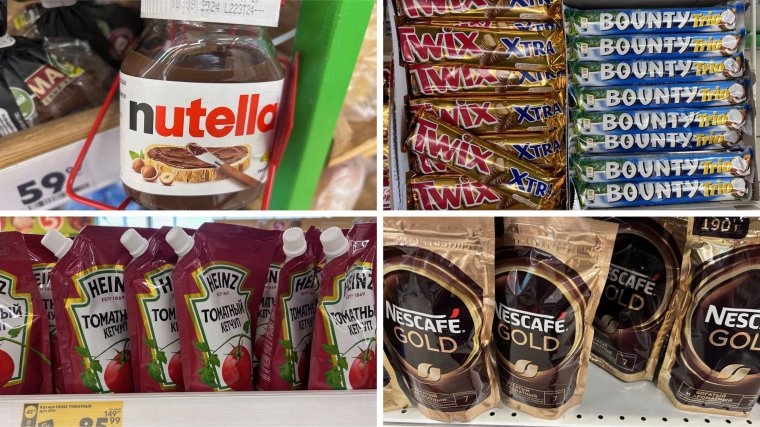

Visiting supermarkets, she was also shocked to find products from many big Western brands still widely on sale. “You can buy anything you want,” she says, “It’s just more expensive than it used to be.”

Among the items she found were Snickers, Twix, Bounty and Kinder chocolates, Heinz tomato ketchup, Nescafé Gold coffee and jars of Nutella.

Although Ukraine’s Western allies have placed sanctions on Russia to prevent trade in many military, technological, industrial and luxury goods, there is no ban on exporting many other items, such as everyday food products – meaning the products she found were being sold legally.

The i Paper asked these companies to explain their exports. Most didn’t respond. But a Nestlé spokesperson said their firm had “drastically reduced our portfolio in Russia” since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, adding: “Our limited offering in the country remains focused on providing basic and essential food items to the local people.” They underlined that Nestlé abides by all relevant sanctions.

It deeply frustrates Jana that wider trade bans aren’t in place, and that more companies haven’t independently taken the ethical decision of ending exports entirely. Some companies, such as Apple and Coca-Cola, have stopped selling to Russia, but their products are imported without their permission through third countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Jana concedes that where Western companies have pulled out, sometimes this has inadvertently helped the Russian economy by allowing local entrepreneurs to fill gaps in the market, keeping more rubles inside the country. For instance, when McDonald’s departed, many of its former outlets were quickly taken over by a Russian chain and are still selling burgers.

Nevertheless, she laments that sanctions have been “completely ineffective”. She hopes the UK goes ahead in seizing the £25bn of Russian assets that have been frozen in Britain, to give the proceeds to Ukraine. “Let’s get the mansions and the yachts,” she says.

The UK is home to many Russian dissidents, from Marina Litvinenko, whose husband Alexander was murdered in London, to Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who spent a decade in Russian jails and was accused by the Kremlin just last month of plotting a coup. Vladimir Kara-Murza, who was poisoned twice and spent years in jail until a prisoner exchange last year, also holds British citizenship.

In contrast to them, Jana states: “I’m not an activist, I’m not a brave person.” Yet she admits that writing her book could anger the Kremlin. She has no regrets, she says, but does she worry about Moscow’s security forces targeting her?

“I’m trying not to think about it,” she says. “We have a proverb in Russia: ‘If you’re afraid of wolves, don’t go to the forest.’ I’m going to the forest, I’m just not thinking about the wolves.”

The Good Russian: In Search of a Nation’s Soul by Jana Bakunina will be released on Thursday (£25, The Bridge Street Press)

@robhastings.bsky.social