The story of a nun’s friendship with a death row murderer was long overdue a UK run, and ENO are just right for the job

A nun and a death row murderer: if ever a story was operatic it’s Dead Man Walking. Big characters, bigger emotions, and stakes higher than both – no wonder Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally’s show has racked up an unprecedented 80 international stagings since its San Francisco premiere in 2000.

But other than a starry concert-performance at the Barbican and an impressive student production at the Guildhall, so far none of these have been in the UK. Snobbery, cynicism, or commercial apprehension? It’s hard to tell what has kept a piece clearly made for English National Opera, with its eye for “issue” dramas and opera-in-English mandate, out of the repertoire. 25 years on, and the work finally arrives at the Coliseum for its fully-staged, professional UK debut.

Based on the life of American nun Sister Helen Prejean (described in her 1993 book, and later given the Hollywood treatment by Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn), the opera follows Sister Helen as she meets and befriends death-row inmate Joseph de Rocher – sentenced to death for the murder of two teenagers.

Opera gets into the emotional cracks other genres can’t reach, and Dead Man Walking finds every cranny in this jagged, pitted story. Heggie’s Barber-meets-Bernstein-via-Broadway language isn’t afraid of sentimentality – gospel-style spiritual “He will gather us around” is the redemptive sweetness running through the opera’s core – but it’s tempered by a salty, bluesy outer layer, as well as the crunch of symphonic ferocity. Multi-Tony-Award-winner McNally provides shrewd dramatic architecture, as well as plenty of vernacular bite. “Have some respect – she’s a fucking nun.”

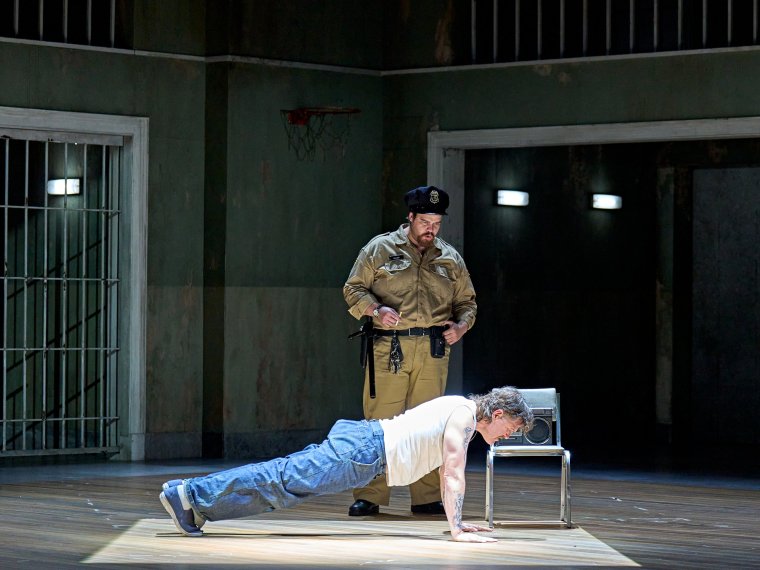

ENO artistic director Annilese Miskimmon’s staging keeps things minimal. A single set frames all the action, trapping us along with Joseph in the drab inner courtyard of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. There’s little sense of the heat and sweat that ooze off the score; no pastoral relief to silhouette the horror of the lakeside murders in the opening scene; no colour except from a vending machine; no escape. It’s claustrophobic, certainly, but also just a little non-committal.

It’s a similar story with both the chorus and children’s chorus; neither quite delivering the punch this large house needs, especially when riding the surging volume of Kerem Hasan’s orchestra – no quarter given.

But the solo singing is superb. Mezzo Christine Rice pours balmy, liquid phrasing into Heggie’s grateful writing, the uncomplicated radiance of her tone set into relief by her physicality – tomboyish, ill-at-ease, an unlikely and often unwilling ministering angel. Baritone Michael Mayes refuses to court sympathy as a blustering Joseph, voice molasses-dark, seductively bittersweet. Vulnerability and denial jostle in Sarah Connolly as his mother, and there’s bags of power from Madeline Boreham’s Sister Rose.

Contemporary popular opera: it sounds like a contradiction in terms, but Dead Man Walking squares the circle. Songful and direct, serving up moral ambiguity with musical conviction, it’s music-theatre in the purest sense. If you want West End bang for much less than West End buck this autumn, this show is the answer.

To 18 November