‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ author’s entertaining memoir wittily recounts her life and (many) loves – and her accidental rise to feminist icon

In 1984, the Canadian author and poet Margaret Atwood was in Norfolk, England, struggling with a book she’d been writing for a while. As she tried and failed to make the manuscript work, an old idea that had been percolating for some time floated to the top of her consciousness instead, a novel she had been considering for years but “shelved […] because I thought it was too weird, even for me,” she confesses in her new autobiography. “A future United States that was a totalitarian theocracy? Surely not.”

That “weird” novel was, of course, The Handmaid’s Tale, originally called “Offred” after its main character, a woman subjected to monthly rapes intended to produce offspring for her superior caste householders in a nightmarish near future. Atwood switched to this manuscript instead, and so ended up writing it, coincidentally, in the same year in which one of its influences, George Orwell’s titular dystopia, had been set. (Atwood details other influences here too, including the Reagan administration, her graduate study of New England puritans and witchery and her time visiting East Germany and Czechoslovakia when the Berlin Wall was still standing and the Stasi was operating at full throttle.)

The Handmaid’s Tale went on to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize and over time has helped catapult Atwood to global fame, particularly since the hit adaptation’s first season aired in 2017 – and since the politics and public sentiment of the US have swung sharply to the right.

But its success, Atwood is keen to remind us, was “incremental”. There is, she says dismissively, something “ludicrous” about fame, which is in any case is “indeterminate quality”. “When I was having a crabby day, my teenage daughter would say: ‘Are we feeling a little famous today? I think we’re feeling a little famous. Time for our nap.’”

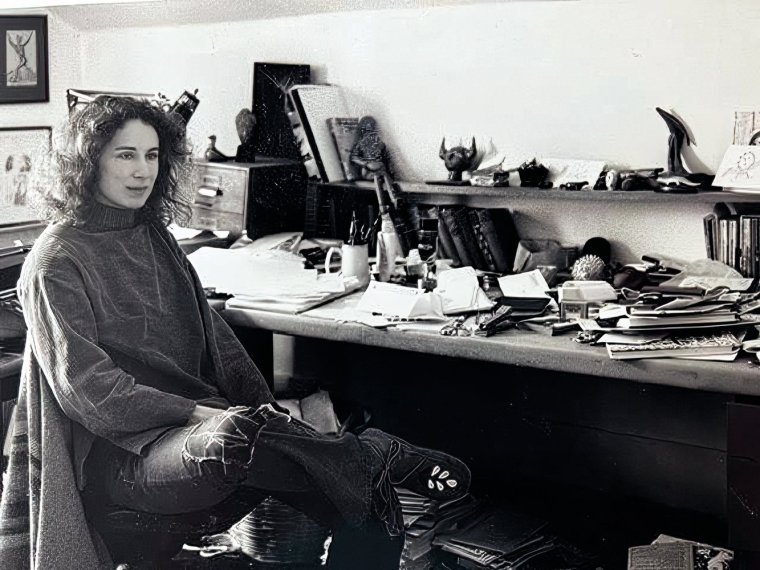

This sort of self-deprecating wit, a humour as dry as toast, makes Book of Lives immensely readable. It is subtitled A Memoir of Sorts, but really it is a rather old-fashioned sort of autobiography, a far cry from more new-fangled kinds of memoirs, with their narrative arcs and redemption stories. (Atwood does not give the impression that she would ever be given to the kind of self-regarding sentimentality that would even allow for a personal narrative arc).

This is quite simply the tale of Atwood’s life, drawn from memory and extensive journals. “Both my parents were from Nova Scotia,” it begins. “My father was born in 1906, my mother in 1909” – before tracing what followed, through her career successes (she later won the Booker for The Blind Assassin in 2000) and personal entanglements (there are a lot of boyfriends) to her own old age, finishing the book, as she now is, at the age of 85.

In other hands, such an intensely linear, chronological structure might feel plodding. But Atwood’s anecdotes and musings are so entertaining, and the fabric of her life, the foundations of her evidently resourceful, hard-working and fiercely funny character so interesting, that this book is never plodding. That said, there are so many geographical moves (and, yes, so many boyfriends) that readers may spend a fair amount of it asking themselves: “Wait, where are we again? Who is that again?”

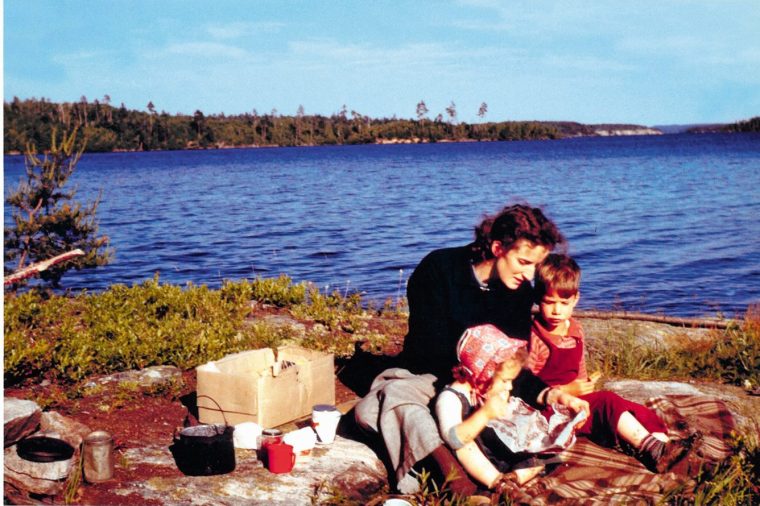

Atwood is born to an epidemiologist, the “extreme bootstrap puller” Carl, and the not academic but enormously resourceful Margaret. The couple take their two small children Harold and Margaret junior (there would later be a third, Ruth) to the Canadian bush for two thirds of every year for Carl’s work on insects. There they live in very basic houses built by Carl himself, without electricity, running water or a phone. Her mother prefers this to the few months they spend each year in cities, because “there’s less housework”.

Later, Atwood will claim that she was not quite the women’s rights trailblazer she was made out to be. She actually wrote her first novel, the proto-feminist tract, The Edible Woman, long before it was published in 1969, and before second-wave feminism had even emerged; it just got stuck on a neglectful editor’s desk.

Her days studying in Harvard are a mish-mash of fearlessness as one of the few female graduate students, but also acquiescence, donning unfeminine tweed outfits the better to fit in at lectures. Twenty-something Atwood cares more about getting her work done than activism.

However, it’s easy to see in her childhood years an embryonic, entirely un-flashy form of feminism, as well as a style of living that lends itself to creativity. Atwood’s parents are equal partners. Her mother fights off bears that raid the food tent in the Quebec forest, and leaves her kids to play with snakes and sew their own clothes.

“Peggy Nature” as Atwood comes to be known following a Jewish summer camp where she entertains young boys with prints of mushroom spores, is reading and writing her own stories by the age of five. Atwood’s sense of injustice for her sex only appears, like her fame, incrementally, exacerbated by the misogyny embedded in her profession. “‘She writes like a man,’ a fellow poet said of me in the early 70s, intending a compliment. ‘You forgot the punctuation,’ I told him. ‘What you meant was, She writes. Like a man.’”

“How often have I heard at book signings, ‘But your writing is so dark! I wasn’t expecting you to be so funny!’” Atwood writes. Indeed. She is a hoot. Describing a moment when she spotted an old English teacher featured in a documentary about her years later, Atwood writes that Miss Smedley said: “Peggy showed no particular ability in my class.” She adds: “This was true and I admired her candour.” Elsewhere, she says that a boyfriend once gave her, for Valentine’s Day, “a real cow’s heart with an arrow stuck through. My kind of guy!”

There are plenty of literary origin stories here (such as the real bullying in Atwood childhood that prompted the fictional cabal of awful pre-teen girls in her novel Cat’s Eye), plus of course a sprinkling of literary glamour. Atwood was right at the heart of a burgeoning Canadian literary scene; she describes having lunch with Ted Hughes, befriending publishing icon Diana Athill and partying with the celebrated theatre director Tony Richardson. But all of it is written with such spare, dry prose – plenty of dialogue, not a soppy, self-aggrandising metaphor in sight – that it never particularly feels like the life of a famous person.

In the chapter titled “The Handmaid’s Tale”, Atwood has barely paused to acknowledge the success of this bestselling novel before the section ends with her getting on with the next book: Cat’s Eye. Although ferociously intellectual (despite, she confesses, being very bad at spelling), throughout this book it is clear that Atwood prizes other things above academia: nature, common sense, family. Her parents aren’t thrilled when she announces, aged 16, that she’s going to become a writer, and there’s clearly a part of Atwood that cleaves to their more rustic identity. This is not a family that fetishises the literary scene.

The blunt style on display here is, perhaps, what so bothered the writer Mary McCarthy when she gave A Handmaid’s Tale a scathing review in The New York Times in 1986, objecting to writing that was, she wrote, “undistinguished in a double sense, ordinary, if not glaringly so, but also indistinguishable from what one supposed would be Margaret Atwood’s normal way of expressing herself”. (This review clearly still bothers Atwood, as she references it here.)

Most people would now probably disagree with McCarthy’s conclusion that this “normal way of expressing herself” is a bad thing, and certainly here in Book of Lives, it is a huge part of the appeal. Atwood does not enjoy hyperbole. She plays down the highs and lows of her own loves and losses, weaving them so amusingly into the wider tale that occasionally you might wonder if anything bothers her at all.

And yet if the book does have a narrative arc it is Atwood’s meeting of the writer Graeme Gibson, her partner of 36 years, and father of her daughter, Jess. Gibson died in 2019, just before the book tour for The Testaments, her sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood went anyway. “The busy schedule or the empty chair? I chose the busy schedule. The empty chair would still be there when I got home.”

Atwood never openly says how much she adores Gibson but it’s abundantly clear anyway. She devotes several chapters to his own childhood, as if he’s a central character. (He may be a central character to Atwood but one does wonder whether readers want to know so much about his star sign; perhaps surprisingly, Atwood is rather superstitious and gives a lot of credence to horoscopes, tarot readings and psychics).

Barely given to introspection elsewhere, Atwood also dedicates long passages to writing to her own “inner advice columnist” to seek help on various issues with Gibson early in their courtship, such as the difficulties with his ex-wife Shirley (not quite ex when Atwood and Gibson meet).

Interestingly, Atwood generally seems uninterested in the kind of “squalid moral book-keeping” so typical of memoirs, as she notes in her introduction, except for where it concerns Shirley, whom she increasingly paints as a bitter, vengeful ex intent on ruining Atwood’s reputation and taking her money.

Both Gibsons are now dead, but I did wonder what Atwood’s two stepsons make of this portrayal of their mother. To a reader, of course, it’s the type of bean-spilling that gives a memoir some deliciously naughty bite. In any case, Atwood and Gibson have an adventurous life, hopping (in a mirroring of Atwood’s own childhood) from cities to farms, from Canada to America, from the Americas to Europe, baby and typewriters in tow.

Always, though, there is a sense of stability to this nomadic existence once she meets Gibson. Underneath Atwood’s acerbic approach to ex-wives and misogynist contemporaries, is, I think, a deeply sentimental and family-oriented person, just someone who prefers their sentiment in action, not words. A section about her dear father’s death is titled simply “Carl departs.”

But then the book ends not with Atwood’s own words, but with his. This final chapter, “Becoming an Epidemiologist”, is taken from Carl’s own papers recalling his early schooling and the discovery of a caterpillar that prompted his lifelong love of insects. “Ex nihilo nihil fit,” writes Atwood: Nothing comes from nowhere.

Atwood’s choice to end not with her own life but with the minutiae of her father’s is a moving tribute to him and to the humbling idea that Atwood’s success is not just her own. Where does great writing come from? From everything – and everyone – that came before.

‘Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts’ is published by Chatto & Windus on 4 November, £30