A third book of essays from the literary powerhouse is patchy and strangely bloodless

If you’re reading this on a screen then I hope you’ve been awake for more than an hour. Or at least Zadie Smith does. More than once in the essays collected in Dead and Alive, the most important English novelist of the 21st century, who turned 50 this month, addresses the ways smartphones have changed our lives. “[That’s] my big piece of writing advice,” she writes. “Try waiting an hour after waking, maybe two. You’re a writer. Even if your subject is the internet itself, you still have a right to take a moment. To observe the contents of your own consciousness and decide what it is you’re interested in.”

Sound advice. So what is Smith interested in these days? Many of the same things that have interested her since she burst on to the scene with her first novel, White Teeth (2000): hip-hop, cinema, class, race, north west London, New York, comedy and the unique power of literary fiction which, for Smith, comes down to style. “I believe in a sentence of balance, care, rigour and integrity,” she writes in “Fascinated to Presume: In Defence of Fiction”. “The sort of sentence that makes me feel – against all empirical evidence to the contrary – that what I am reading is, fictionally speaking, true.”

To readers of Smith’s previous essay collections, Changing My Mind (2009) and Feel Free (2018), this may sound familiar. She has defended fiction repeatedly and she is as passionate about it now as she was 25 years ago. The best defence of fiction, for a novelist, is to write it and Smith has continued to do so, most recently in her sixth novel, The Fraud (2023), her first in a historical setting, and the one which, along with its predecessor Swing Time (2016), received some of the most mixed reviews of her career.

Are we in danger of taking her for granted? If we are then it may be because she has been around for a long time, first publishing at an age (24) when most would-be novelists are writing apprentice works that will never see the light of day.

The success of White Teeth catapulted Smith to literary stardom and made her, through no volition of her own, a spokesperson for multicultural Britain. She has been influential on younger writers and, reading her essay here on Toni Morrison, in which she mentions a generation of Black women authors who were “daughters of Morrison”, it is tempting to suggest that today there are daughters of Smith writing on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet she has gone from being prolific to ubiquitous. In recent years, Smith has co-authored two children’s books with her husband, the poet Nick Laird, and written her first play and numerous articles as well as The Fraud. The result is that some of the pieces in Dead and Alive feel predictable.

Take her piece on Stormzy’s 2019 Glastonbury set. Smith has a long-standing interest in rap music (she has interviewed Jay-Z and refers to figures such as “Kanye” on first-name terms) but I couldn’t help finding her essay a little strange – she made the bizarre choice to write about the performance in mock-Shakespearean language: “Our young black king, the warlike Michael, entered stage left. His armour, stab-proof and street ready, bore upon it the rusted colours of his country, and, although he was young, no one in the field doubted that he looked the part.”

This first appeared (in The New Yorker) when Stormzy’s bars were still ringing in his audience’s ears and commentary was unnecessary. It looks even sillier six years later. It is the job of writers to write about what moves them, but they must permit themselves, and their readership, some unpublished thoughts when what they say adds nothing to our understanding of a subject.

One of Smith’s most appealing qualities as an essayist is her honesty, which is on display when she writes about Hilary Mantel following the two-time Booker Prize winner’s death in 2022. It is the last and longest essay in a section entitled “Mourning” in which Smith pays tribute to, among others, Martin Amis, Joan Didion and Philip Roth. They offer straightforward praise, but Smith’s piece on Mantel, in which she reveals she hadn’t read Wolf Hall at the time of its author’s death, is beautifully frank and relatable: “I was having the first inklings of wanting to write a historical novel myself, and had the strong pre-monition that if I read Hilary’s, and it was as good as everybody was saying, I would never write my own.”

Elsewhere, Smith’s openness invites criticism. “Essays are easy,” she says in an interview collected here, when asked to compare her fiction and non-fiction. Perhaps this is why Dead and Alive feels insubstantial. In her novels and essays, Smith has always possessed fluency and stamina, but too many of the pieces here are slight and the book is scrappy, padded out with speeches and lectures as well as an interview.

Smith is excellent at channelling her anger in essays about 14 years of Tory rule in Britain, which she wrote on the eve of last year’s general election. And about those who quietly profit from the destruction of the planet and absolve themselves: “One thing novelists know is that nobody really thinks of themselves as the bad guy…”

But her reflections on a topic that is genuinely divisive are a chin-stroking mess of equivocation. The essay “Shibboleth”, Smith says in a note, was published “on 5 May 2024, during the heroic student protests against the war on Gaza”.

In this piece, Smith qualifies her support for the protests with concern about the language used by some protestors which, she worries, could make Jewish students feel “unsafe on campus”. On its own, and out of the context of the extremely tense moment, this doesn’t sound unreasonable. But when the article appeared in the New Yorker, many readers voiced dismay that Smith was amplifying the bad faith pretext used by the universities and police for violently breaking up the protests and arresting students.

At times in Dead and Alive, Smith sounds tired of the obligations – talking about her books, appearing at public events, expressing opinions on current affairs – that come with literary fame. She tells an interviewer she is “retiring from the commentary game for a while. I’m so sick of the sound of my own voice.” Although she does add a self-deprecating footnote (“Hmm”) to acknowledge that we are reading this in a collection of her commentary.

Dead and Alive contains flashes of the intellectual vigour and deep reflection that have always lit up Smith’s essays. Her pieces about where she grew up are rich and moving and she still has her finger on the pulse of her place and time. Her warnings about the age of the algorithm, and why reading fiction is better than scrolling through social media, are persuasive and welcome.

But there is less surprise and intensity in this book than in her previous collections and I finished it wishing Smith would follow her own advice and take a moment – both to work out what she has to say about a subject and to make sure it’s something we haven’t heard her say before.

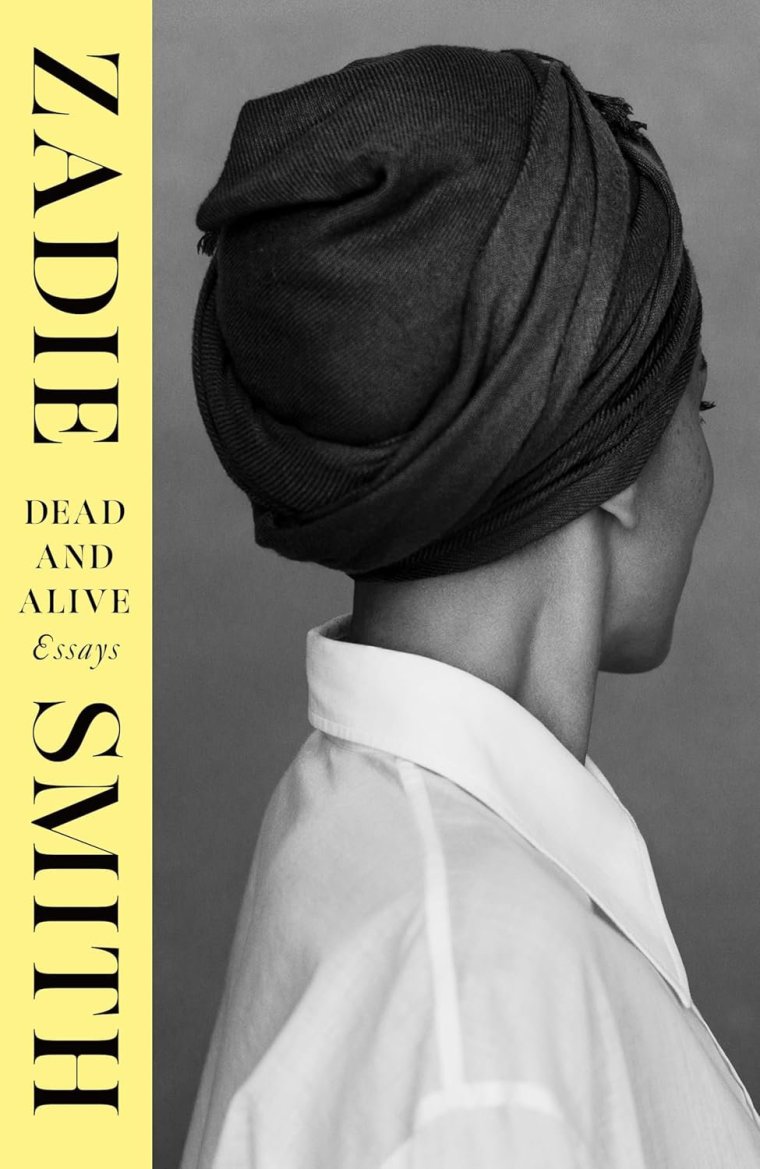

‘Dead and Alive’ by Zadie Smith is published by Hamish Hamilton, £22