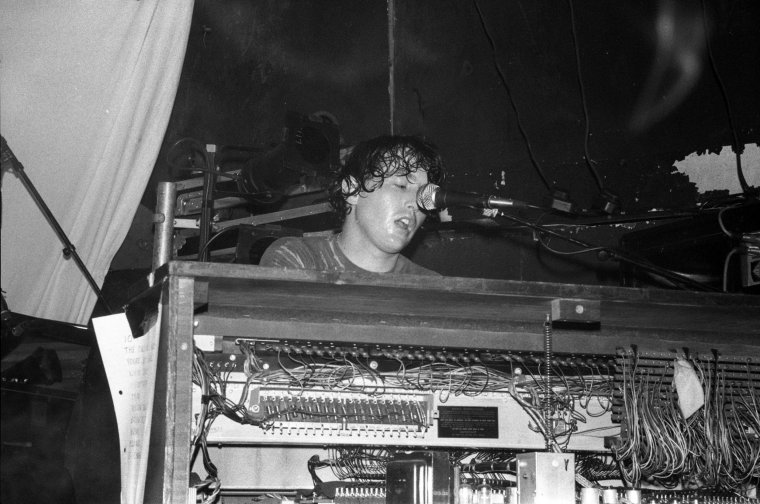

On 22 July 1996, The Charlatans were struck by tragedy. Rob Collins – the band’s wild-card keyboardist who in 1992 was jailed for his part in an armed robbery – was killed in a car crash aged 33 at Rockfield in Monmouthshire, the Welsh studio where the band were recording what would be their classic album, Tellin’ Stories.

In the shock of grief, they decided to just press on: within three weeks, they were supporting Oasis at the legendary Knebworth show with a replacement keyboardist, the late Martin Duffy of Primal Scream (Liam Gallagher dedicated “Cast No Shadow” to Collins).

“Adrenaline,” singer Tim Burgess says, when I ask how they managed it. “We went to do it not knowing whether it would be like the greatest show on Earth or the natural dismantling of the band.”

It was neither, but triumphant all the same. Tellin’ Stories then became their best selling album, going platinum and spawning their three biggest hits: “One to Another,” “North Country Boy” and “How High” (which all charted higher than their enduring 1990 indie-disco staple “The Only One I Know.”) But returning to Rockfield never felt like an option. “I swore that we’d never go back,” Burgess says. The band agreed. “It was unspoken. We couldn’t. Rob’s accident and death happened at the bottom of the drive.”

Yet over 25 years later, The Charlatans returned to Rockfield to record their 14th album, the adventurous, excellent We Are Love. Burgess did briefly go back by himself 15 years ago, on a fact-finding trip for his 2012 autobiography Telling Stories. “I went there and thought, ‘Will I even recognise the field? How will I feel emotionally?’ But none of the band had done that until this album. So it was good to all go back there and be as one.”

Burgess refers to the process as “hauntology” – the concept of the present being haunted by the past – and psychogeography, how your location affects your behaviour. These high concepts played into the band’s thinking. “A lot of [the album] came from a sense of place, the feeling that we were a Rockfield band,” he says. They drop reminders of their past their past throughout the record: the runout groove from debut album Some Friendly; old song titles like “Impossible and “Opportunity.” “All these little Easter eggs.” Very Taylor Swift. “Very Taylor Swift,” he concurs.

But something rather strange did happen during recording. “There was one day where nothing was working in the studio. We couldn’t get anything going. It was just weird. And then about five o’clock in the afternoon, I went on Instagram and realised it was the anniversary of Rob’s death.” That really is hauntology. “You’d think that he would be helping us to continue,” he smiles. “But he was always the prankster.”

It doesn’t seem plausible that The Charlatans are now 37 years old. For a start Burgess, a chilled, happy presence on the couch of his PR’s central London office, can still pass for considerably younger than his 58 years. But their career stretches back to 1988, when bassist and songwriter Martin Blunt formed the band in the West Midlands, which included lasting core members Collins and drummer Jon Brookes. Burgess joined a year later, a charismatic, Jagger-lipped, bowl-cut pretty boy of a frontman, sparking them into action.

Their early-60s mod-inspired Hammond organ sound incorporated the contemporary groove of the acid-house-with-guitars Madchester scene of The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays (the band had moved to Northwich; Burgess was a regular at the Hacienda). By the mid-90s, the band’s move towards a more guitar-orientated sound chimed with Britpop. The Charlatans actually released a single, “Just When You’re Thinking Things Over”, on the same day Oasis and Blur took part in the “Battle of Britpop” with “Roll with It” versus “Country House”. “I always feel pretty good because we were single of the week in NME,” he smiles. All told, The Charlatans have had three of their nine top 10 albums reach No 1, and 22 top 40 hits.

But it hasn’t been without trauma. In 2013, Brookes died of a brain tumour. Meanwhile, Burgess struggled for years with heavy addiction to cocaine, which he says truly spiralled after Collins’s death. “We all dealt with it very differently. I pretty much did 10 years to the day of self-medication. Was that the best way of doing it, or was it not? Who really knows? Martin really took Jon’s death badly more than anybody. We probably should have all gone to therapy. But I do enough of that now.”

Burgess got clean in 2006 during a 12-year spell living in LA with his first wife (he’d moved there in 1999). Is it easier to get things done now? “Well, I’m not gonna take away some of those amazing songs that that I was involved in f**ked out of my brain,” he says. “But it’s easier now. Towards the end of my druggie phase, my communication skills were pretty much nothing.” These days it’s daily transcendental mediation and healthy living – “smoothies and protein powder over pints of Stella,” he smiles – and parenting his 12-year-old son, Morgan, with his ex-partner Nik Void of Factory Floor. “I love it. I’m trying to be a good dad. Not amazing, not shit, just good. Good is great, because good is reliable. Amazing is just impossible.”

It’s been eight years since The Charlatans last released an album, 2017’s Different Days. Covid and the scattered geography of their members (guitarist Mark Collins, keyboardist Tony Rogers, drummer Pete Salisbury) played its part in the gap; in the interim Burgess released three solo albums and one EP, and created the lockdown sensation Tim’s Twitter Listening Party, which then became a podcast. When they reconvened, it took a while to click. But they were soon working on songs with the aim of “changing the narrative” about The Charlatans.

“I didn’t say that,” Burgess says quickly. “That’s Martin. I think it’s his favorite quote,” he adds, smiling. Is he behind it? “I am behind it. What does it mean? I think it comes down to the hauntology thing. We’re bringing stuff in from the past, shovelling it into the pot, all the memories, acknowledgement of anyone who’s been involved in the band, the stories, the history, and kind of redefining it. Making it into something that’s new and present and forward-thinking.”

We Are Love certainly pushes The Charlatans into new terrain. The organ-led single “Deeper and Deeper” is recognisably them (“if you heard that and it wasn’t us, you’d say it was a rip-off”). But the second side is expansive and experimental: from the field-recording ambience of “Salt Water” to the sumptuous closing trilogy of songs that take in Beatles-like harmonies and recall everyone from The Beach Boys and The Byrds to Spiritualized and krautrock. “The last three songs is our attempt to do an Abbey Road. It’s subjective as to whether we pulled it off or not. But I think that we did.”

Burgess said he wanted to explore the philosophy of love. Why? “Well, relationships, relationship breakdowns,” – Burgess split last year from Catastrophe and Bad Sisters actor and writer Sharon Horgan – “starts of new relationships, parents’ relationships, kids, the 35-year relationship with the band – it all just seemed to really be in my life.” He saw a quote from film-maker John Cassavetes that said love was the reason why he made films. “And I just thought, this is it. When you first start out in a band, you say you’re not gonna write about love. This was just about love.” So is that an age thing? “It’s an ownership of something that I knew a lot about.”

One song, “Glad You Grabbed Me,” is about Martin Blunt. Creatively, he says, “I think me and Martin are more tuned in than people give us credit for.” But their relationship “is complicated. We both want the same thing, but we both have completely different ways of getting it. And somehow we get there. It’s a battle. It’s not easy, otherwise anyone could do it.”

In “Many a Day a Heartache” Burgess sings: “It’s just rock and roll, but I gave it my all.”

“For sure,” he says. “I’ve been into the depths of debauchery.” I had assumed he meant the whole package: a lifetime of commitment to the art. “That is very true,” he says, as if he’s just realised it himself. “I’m not sure I meant it like that, but it’s true. Because I handed myself over to this.”

The dedication has been rewarded with longevity. Unlike nearly all of their contemporaries, The Charlatans never split up. “Which I’m really proud of. That might not matter very much to everybody in the world,” he says, “but it matters to me that what we have was unbreakable.”

‘We Are Love‘ is out now