Populists accustomed to protest politics often struggle with the boring grind of policy delivery and compromise

As Dutch voters head to the polls on Wednesday for the second time in two years, the man who set the country’s political agenda for two decades looks strangely isolated.

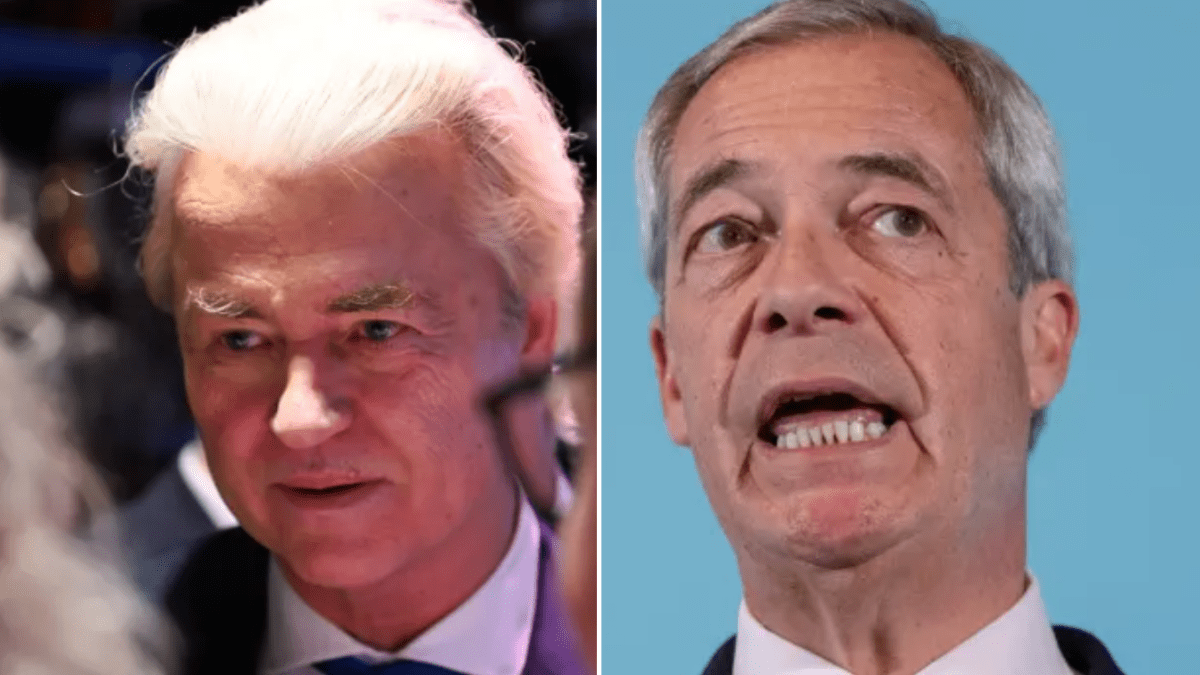

Geert Wilders, the peroxide-haired showman of the Dutch far right, pulled his Freedom Party (PVV) out of the four-party government coalition in June after partners refused to endorse his demand for Europe’s “strictest asylum policy ever”, including army patrols on borders and turning away all refugees. His exit plunged the Netherlands back into an election that could now leave him locked out of power.

It is a humbling comedown for a politician whose victory in 2023 briefly put him at the apex of Dutch politics. Yet where Wilders saw an opportunity to prove hard-right populists could govern, the reality was chaos: fractious coalition infighting, legal red lines blocking his most radical proposals, and furious public disappointment as housing shortages and healthcare pressures went unresolved.

The PVV may still finish first, but it has shrunk from its 2023 election high when it won 23.5 per cent of the vote.

Now, it is vying with the Green-Left/Labour GL/PvdA alliance, the liberal D66 and the Christian Democrat CDA: all four are currently polling at between 12 and 18 per cent.

Tellingly, almost every other mainstream party refuses to govern with Wilders who is now seen as too toxic. Former ally Dilan Yeşilgöz, leader of the free market VVD, now brands him “an unbelievably untrustworthy partner” who “runs away when things get difficult”.

In a system where no party ever wins a majority and coalitions are stitched together among a jumble of up to 16 parliamentary groups, popularity alone is not enough. Wilders may once again dominate headlines. He will not dominate the cabinet room.

That Dutch lesson matters far beyond The Hague. Like Wilders, Britain’s Nigel Farage is charismatic, media-hungry and laser-focused on migration to fuel outrage and shift debate rightwards. Farage, whose Reform UK party is currently topping domestic polling, may see in Wilders both inspiration and warning.

The inspiration is clear: Wilders built a durable populist machine without needing traditional party structures, pushing centrist rivals into adopting harsher stances on migration. His issues became their issues.

Yet the warning is sharper. When given a share of governing power, populists accustomed to protest politics often struggle with the boring grind of policy delivery and compromise. Wilders pulled the plug rather than face the constraints of laws, budgets and coalition partners.

The result is a political landscape swinging back toward steadier hands.

Both the CDA and the Green-Left/Labour alliance have surged, campaigning on “normal, civilised politics” and promising to fix the housing crisis and rising healthcare costs that voters say matter far more than anti-asylum theatrics. A broad “middle coalition” now looks the most plausible outcome. The front-runners for prime minister are Labour leader Frans Timmermans, a former EU Commissioner and Dutch foreign minister, and CDA leader Henri Bontenbal, who only entered politics four years ago. It would be a modest victory for moderation in a country tired of performative outrage.

For Farage, the Dutch election offers a glimpse of the populist bubble bursting when forced to confront real-world responsibility. If Reform UK ever moved closer to national government, the question would be the same: can a politics built on gleeful disruption survive contact with governing reality?