The day before I meet Lang Lang, in the bar of a plush south London hotel, the Chinese classical pianist and global superstar visited a special education school in west London. There he met William Blyth, a 15-year-old pupil with autism who is a Young Ambassador of the Lang Lang International Music Foundation, an organisation inspiring the next generation of piano players across the world, particularly the underprivileged. There is a lovely, moving video on YouTube about William’s journey from non-verbal child to more confident teen via his love of the piano.

“William’s become a very friendly, very optimistic person through music,” Lang Lang says. “He used to barely talk to people. We have a very similar situation in China as well. We had many kids having autism, but through the process of learning piano, they become who they are. Music became their best friend.” The LLIMF takes its flagship programme “The Keys of Inspiration” to schools across the UK, US and China. “The idea is to make piano very approachable, make it educational. So that’s what my foundation is doing. We want to make their life easier than mine was.”

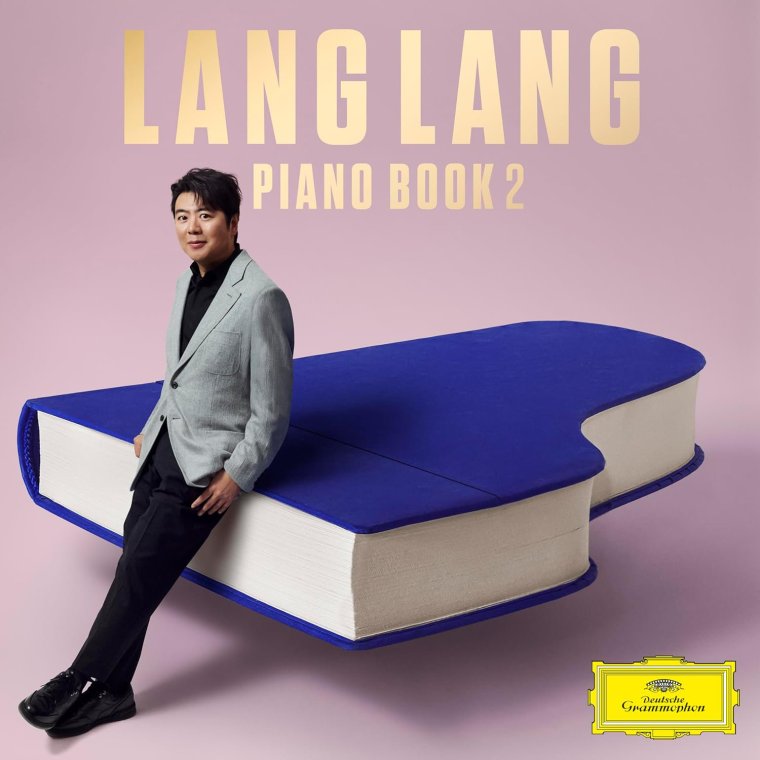

That wouldn’t be too difficult. Lang Lang now enjoys a remarkable career with celebrity status; he performed to a reputed audience of four billion at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics; he’s played for world leaders and royalty including the late Queen Elizbeth and King Charles; album sales are approaching 20 million worldwide. His affable turn as mentor and judge on the first two seasons of Channel 4’s reality competition The Piano made him more of a household name in the UK, and a few days after we meet, he will appear on Strictly Come Dancing. His 2019 album Piano Book – a collection of his most loved piano tracks designed to introduce the classical genre to a new generation – has more than one billion streams. “It really, really was a sensation in a way that we never thought. It’s been really powerful.” The second part, Piano Book 2, was released earlier this month.

But Lang Lang’s origin story is extraordinary. Playing piano by two, taking lessons at three and performing in public aged just five, it’s not too much of an exaggeration to say the piano is all Lang Lang has ever known. His father, a policeman-turned-mentor, concocted a plan to make Lang Lang the number one classical pianist in the world, and pushed the young Lang Lang to extreme lengths.

That first recital took place in front of 800 people at the local youth club in Shenyang, the industrial area north-east of Beijing where Lang Lang grew up poor. “I was a little bit overwhelmed. I had a problem in my early time – before every major competition, I can’t sleep. I was too young. Maybe when I was a kid I wanted to win too much. So that got me a bit crazy. In a way it’s good, but in other ways, not so healthy. It’s very unnecessary.”

But that was nothing compared with the pressure his father placed upon him. After he quit his job as a policeman, his father left his mother behind and moved with Lang Lang to Beijing in pursuit of a place at the prestigious Central Conservatory of Music. They lived in absolute poverty with five other families in a slum with just one bathroom and one toilet – “very, very, very, very [slum-like],” says Lang Lang, “no gas, no heat” – surviving off money his mother, a musician who worked on rice farms, would send in a package.

Lang Lang would practice for hours every day – before school, at lunchtime, after school, sometimes starting at 5am. But when aged nine Lang Lang failed to get into the conservatory, his father went apoplectic. He told his son to kill himself: he even offered Lang Lang pills, and encouraged him to jump off the balcony. Lang Lang says his father felt the shame of failure, especially given his sacrifice.

“For me, it’s not the end of the world, but I feel very bad. But for the parents at that time, they think it’s more than that,” he recalls. Is this specific to his father, or part of Chinese culture more widely? “I would say people [in China] are highly competitive. It seems that way for me, compared to western culture. But I was really also wanting to become a musician on the world stage. So in a way, it worked. But if someone didn’t have my drive, they probably would have collapsed.”

Has your dad realised how pushy he was? “Yeah he realises now, but it’s too late,” he says laughing loudly. “He could apologise to me every day. What’s the point?” Did he apologise? “He never apologised anyway. But he changed a lot after I grew up. He kind of let it go. He didn’t push me so much any more, which is good.”

All’s well that ends well: Lang Lang eventually got into the conservatory, before leaving the slum and moving to Philadelphia at 15 to continue his studies. But it meant when Lang Lang performed at the Beijing Olympics, a then 26-year-old put forward as a face of the new younger, outward-looking China, there were mixed emotions. “It was a complicated feeling,” he says. “During my previous time in Beijing, I did have five years of very, very difficult life. Then to come back to this, the biggest show, and to play in that stadium, with everybody watching, there was this enormous tension. But a lot of excitement. It was bigger than a dream.”

It is surprising that, outwardly at least, Lang Lang shows no adverse effect to such a stressful childhood. In fact today, floppy-haired and dressed down in a dark overshirt – he doesn’t look anything like his 43 years – you could barely meet a more jovial person. “Yeah, although my childhood was difficult, I overcome at the end of the day,” he says. “I’m very, very lucky.”

It’s why Lang Lang is so determined to use his good fortune for the advancement of others. He says a trip to Africa in 2004 as a Unicef ambassador (he was just 21 at the time) showed him how music, the piano specifically, can bridge the gap between cultures and circumstances. He also knows how hard it can be to be disadvantaged, or to be seen as an outsider. Twenty years ago, the western classical music scene was suspicious of the Chinese former child prodigy before them. “In the beginning, it was hard for people to understand that somebody from a different culture is trying to break through to this old tradition from Europe. It was kind of like, are you in the wrong place?” He laughs. “I’m not blaming it. I [would] have the same question. If somebody [foreign] is trying to play Chinese violin in China, I will ask, ‘So what is your intention?’”

In truth, the classical world remains suspicious of Lang Lang. In classical terms, Lang Lang is a radical. He collaborates with artists as diverse as Ed Sheeran and Metallica and makes albums of Disney songs (2022’s The Disney Book). For Piano Book 2, a 32-track interpretation of Lang Lang’s favourite “miniature masterpieces”, he performs Bach, Mozart, Satie, Debussy. But it also features music from contemporary culture, including the anime TV series Naruto, the soundtracks to La La Land, Amélie, and Cinema Paradiso, as well as Black Myth: Wukong, a monkey-featuring action role-playing video game.

Is he a gamer? “I’m not so into it, but it’s important to know what’s going on. The gaming world, especially the music, has become very popular among the younger generation.” This is the sort of thing old gatekeepers turn their noses up at. “Each one of us has our own ideas [about] how to develop this art, how to respect this art. If we always think about it in a very isolated way, then as a Chinese [person], how come I play classical music? Then you will never reach that far. I agree we need to protect classical music. But the new generation needs a new audience. If you are a 15-year-old, you need your generation behind you. They cannot have an audience of 80-year-olds.”

Lang Lang’s celebrity status also sits uneasily in a genre that can be sniffy about anything mainstream. “In the classical music world, it’s very simple. You have to play well. That’s it. For sure, once you are more famous, you will get more criticised. But if you play really well, it’s no problem. But if you start to have problems then people will say, ‘Hey, this guy is not serious.’”

It has been a criticism levelled at Lang Lang from old-school critics – that he overplays, that his style is too elaborate, too modern. “No,” he says, “I never believe I’m overplaying. But it’s true that I’m getting more mature, that’s for sure. My style has changed a bit over the years. I think with the experience, with the naturalness of developing, I think I will become better and better. I’m quite confident about that.”

Lang Lang’s new album ‘Piano Book 2’ is out now on Deutsche Grammophon