Iceland is light years ahead of Britain for gender equality, according to Icelandic women – but they warn that it’s no paradise

When it comes to the best place in the world to be a woman, one country consistently comes out on top.

Led by a female president and prime minister, and other women in senior ministerial and official positions, Iceland is regularly ranked as the world’s most female-friendly place to live.

For 25 of the last 50 years, a woman has been head of state, and last year, 48 per cent of the parliament members were female – compared with the 40 per cent female MPs elected in Britain last year.

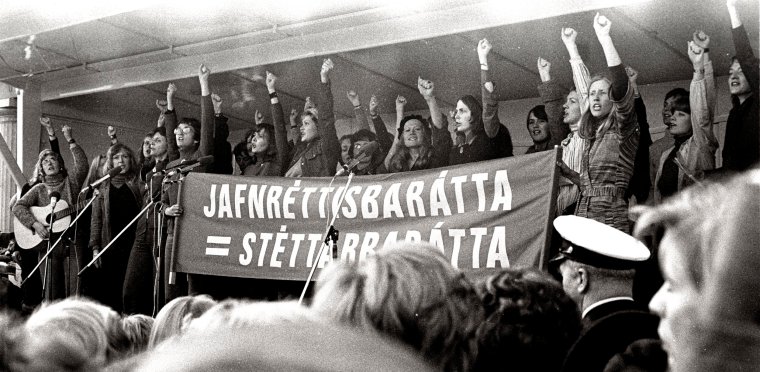

The strike that changed everything

However, 50 years ago, Iceland looked very different.

Women’s work – paid and unpaid – was valued less than men’s, and women earned about 40 per cent less than them.

On 24 October 1975, women all over the country went on strike, refusing to go to their paid work or undertake any housework or look after children. Soon after the strike, Iceland passed the Gender Equality Law, aiming to promote equal rights and opportunities for men and women.

Today, Icelandic women are striking again to celebrate the nationwide strike’s 50th anniversary and to call for further progress to tackle gender inequality.

Unnur Agustsdottir, 70, was 20 when the strike took place. “There was a lot of discussion about women’s rights,” she told The i Paper. “It was then that women really started to wake up. And then there was the women’s strike in 1975.”

Before then, the men in Agustsdottir’s family made all the decisions, and women were judged differently. “If a man went out, got drunk, and slept with lots of women, it was tolerated, but it wouldn’t be tolerated if a woman did the same,” she said.

She recalled a friend of hers, a single mother of two boys, finding out she was getting paid less than the man next to her. When the friend complained to the boss, she was told: “You have to think about the fact that he has a family to provide for. That is what bosses thought – men were the providers and should be paid more,” she said.

Jasmina Vajzovic Crnac, 44, a Red Cross worker who in 1996 fled Bosnia for Iceland after the war told The i Paper how grateful she was to live in Iceland, especially after becoming a mother to her four children.

“I got paid 80 per cent of my pay for six months, and my husband took off for three months at 80 per cent pay when I went back to work,” she said, which allowed him to spend time with his children, reinforcing his equal role as primary caregiver.

“I could have a career and be a mother.”

“In my country, Bosnia, men do work out of the house, and women care for children,” she said. “In Iceland, there is a high percentage of women working outside the home.”

With so many women in leadership, women were inspired to work and have a life outside of the home.

She also praises the flexible working rights for families. When her children are ill, she has never struggled to have time off to stay home with them. “I can plan when and where I work,” she said.

How Iceland compares with Britain

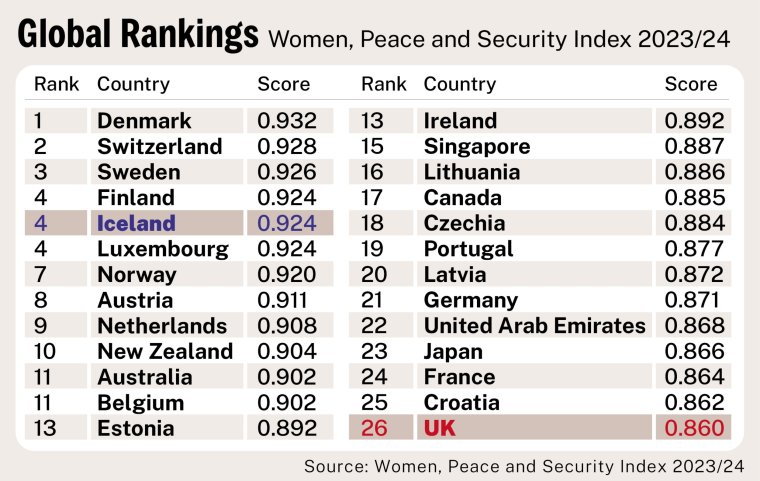

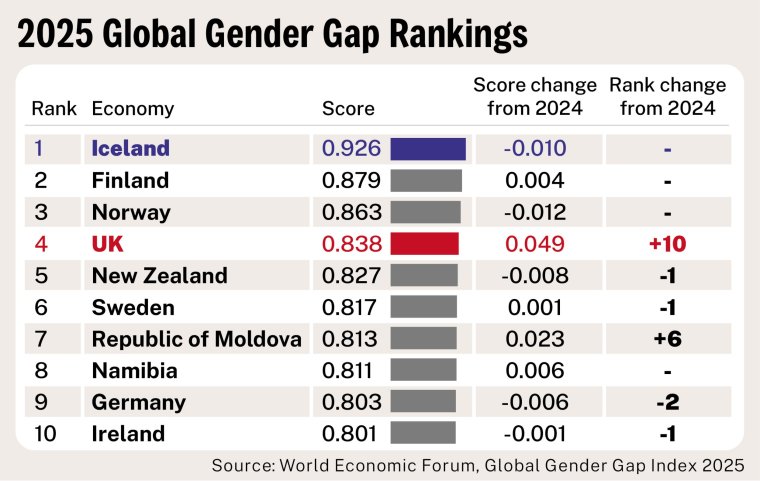

Today, Iceland is once again top of this year’s Global Peace Index – for the 16th consecutive year – top of the Global Gender Gap Report, and in fourth place on the Women, Peace, and Security Index.

In contrast, Britain languishes at 30th on the Global Peace Index and 26th on the Women, Peace, and Security Index. Although the UK can take some hope from the Global Gender Gap Report, in which it came fourth, behind Finland and Norway.

Meanwhile Iceland comes third in the World Happiness Report, after Finland and Denmark. The UK comes 23rd for happiness.

In Iceland when a child is born, each parent is entitled to six months of leave, with six weeks transferable between parents. Standard maternity and paternity leave payments are generally 80 per cent of average income.

This compares with two weeks of maternity and paternity leave, paid at 90 per cent, in the UK. Maternity leave then covers six weeks at 90 per cent of earnings, with the remaining 33 weeks at the same or £187.18, whichever is lower.

Ugla Stefanía Kristjönudóttir Jónsdóttir, an Icelandic woman who has lived in Brighton for years, said Iceland was “light years” ahead of Britain.

“The main difference between the UK and Iceland is the safety and legal rights we have achieved that just haven’t been achieved in the UK,” Jónsdóttir, 34, said. “Iceland is light years ahead of the UK when it comes to gender equality and human rights generally.”

As a result, Iceland felt like a safe place for women compared with the UK, she said. The women’s movement in Iceland feels more cohesive – like women are “in it together, finding solidarity,” rather than “fighting each other” and getting bogged down in “pointless debates.” Jónsdóttir said she planned to return to Iceland to live.

“In the UK, it feels like an uphill battle, and like no progress is being made,” she said. “It seems like the UK has condemned itself to take so many steps backwards – that it isn’t committed to moving forward. In Iceland, people still want to move forward. I’m proud to be part of a country that is progressive, but there is still a lot that needs to be fought for.”

Why Iceland still has a way to go

However, even for Iceland, there is still a long way to go.

Agustsdottir notes that the gender pay gap in Iceland has grown in the past two years, that the labour market remains highly gender-segregated, with women still doing most of the unpaid care and housework.

The gender pay gaps is especially wide in finance and insurance – nearly 30 per cent) – and more than 40 per cent of women have experienced gender-based or sexual violence. Furthermore, it is still women working in undervalued and underpaid sectors such as cleaning and caregiving.

In 2023, tens of thousands of Icelandic women gathered again in a nationwide protest for gender equality and against sexual violence, many of them waving banners reading – “Kallarou þetta jafnretti?” (You call this equality?).

“We must also be alert to the backlash we see today, with the rise of populist and extremist rightwing forces,” Agustsdottir said. “Fighting that trend is crucial if we want to protect and expand women’s rights. These rights have been achieved through the hard struggle of women and must be defended.”

Furthermore, Vajzovic Crnac admitted that other migrant women might not feel as protected.

“Women working lower-paid jobs, who don’t have an education, and who don’t speak Icelandic, face more barriers,” she said. “They don’t have the same power as other women.”

Jónsdóttir agrees that not all women live “happily ever after” in Iceland. “While Iceland is definitely more forward-thinking than a lot of places in the world, it still has its challenges,” she said, adding that she frequently travelled back home to Iceland.

“We haven’t solved sexual violence. We haven’t solved the gender pay gap. We haven’t solved the fact women take on a lot more household and family responsibilities. We haven’t solved that women are the majority of people who suffer from violence.”

She said that when Iceland is painted as a “picture of paradise,” it can deflect from the issues that still need to be addressed.

“People become complacent because everything is just great,” she said. “That isn’t necessarily the case.”

But Jónsdóttir takes strength from the “strong history” of Iceland’s women – “fighting to be seen, fighting to participate in universities, fighting to have the same jobs as men.”