In the months following the 2024 election, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Prescott Watson began to notice a strange phenomenon taking hold among his peers.

Investors who had formerly taken pride in funding innovations like electric vehicles, geothermal energy, and solar power in the fight against a worsening climate crisis, were now warning of the U.S. going to war with China.

Start-ups developing carbon capture systems, hydrogen fuels, and low-carbon cement, had started pitching such climate tech to investors, officials, and the public as critical to U.S. national security. LinkedIn bios, marketing briefs, and sometimes business plans were being rewritten in alignment.

“It’s just funny to see people [who were] so clearly like ‘rah rah climate!’, and now they turn on a dime and they’re like ‘rah rah warfighters!'” Watson told The Independent. “It’s ridiculous… but if I were in these people’s positions, I would be doing the same thing.”

Watson dubs it the “green to guns pipeline”, and it’s just one symptom of Big Tech’s growing embrace of defense technology. After years of caution about getting involved with the U.S. military-industrial complex, both tech giants and start-ups are piling in.

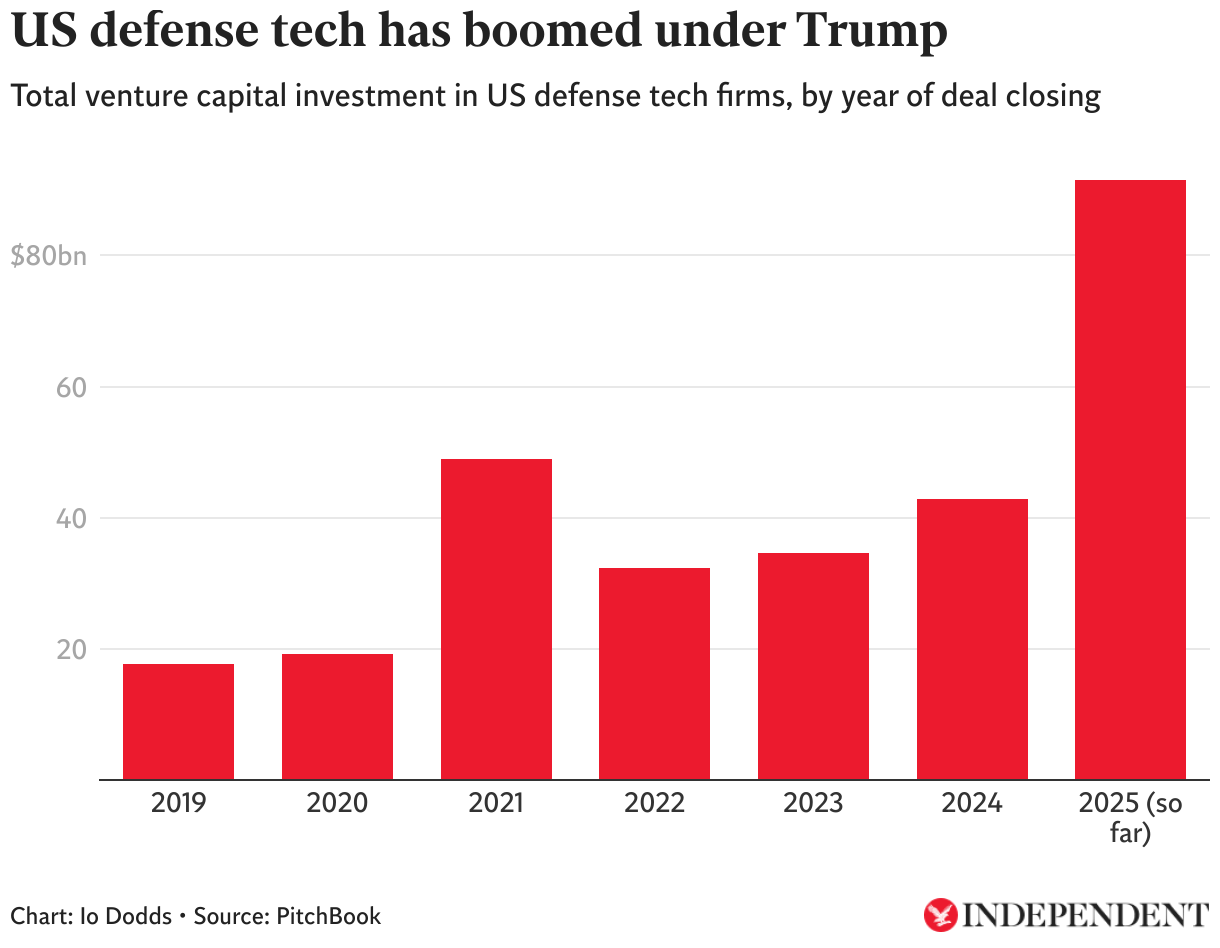

Across the world, venture capital investments in “defense tech” have soared from $19.2 billion in 2019 to nearly $92.8 billion this year so far, nearly all in the U.S., according to data from PitchBook. Simultaneously, equity funding in climate tech last year fell by more than 55 percent from its peak in 2021.

Dedicated defense tech start-ups are building everything from super-long-range stratospheric glide bombs to autonomous drone swarms and laser guns, as well as backend computer systems and new fuels.

Industry heavyweights such as surveillance giant Palantir, autonomous weapons maker Anduril, and Elon Musk’s rocket company SpaceX — the latter two led by avowedly pro-Trump billionaires — are challenging the incumbent military contractors like Lockheed Martin.

Meanwhile, green tech makers are scrambling to catch up. Oakland-based Magrathea Metals, for example, has developed a greener way to produce magnesium, which is used as a lightweight structural metal in everything from car engines and plane fuselages to spacecraft. Right now, an estimated 95 percent of it comes from China.

This time last year, Magrathea’s homepage focused on “radically reducing socioenvironmental impacts” by reducing global steel and aluminum mining in preference for magnesium harvested from seawater. Now it speaks only of a “national security emergency.”

“Ultimately my job as CEO is to make the company successful, and I’m gonna tell the story that’s most likely to achieve that objective,” founder and chief executive Alex Grant told The Independent. “We actually do the exact same work; nothing changes… it’s just a different story.”

Trump is certainly part of the reason. His administration is forging close relationships with Silicon Valley, seeking to step up surveillance of immigrants in the U.S while swearing in executives from Palantir, Meta, and other tech firms as U.S. Army Reserve officers.

On the other side, Trump’s derision for climate change — he calls it “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world” — and habit of interfering with corporations’ business decisions have made many executives leery of anything tinged green.

At its heart, this is big business. Republicans pushed through a record $892 billion defense budget this year, and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth wants an eye-popping $1 trillion next year. Trump also wants to build a “Golden Dome” missile defense system that would probably cost hundreds of billions.

In July, Google, ChatGPT maker OpenAI, and Musk’s xAI all won Pentagon contracts worth up to $200 million to develop A.I. for national security.

Palantir was awarded an Army contract worth up to $1 billion — on top of numerous other contracts signed under Trump — while Anduril has inked deals worth up to $259 million. Even Salesforce boss Marc Benioff, once known for his progressive stances, has reportedly pitched Immigration and Customs Enforcement on a major deal.

These shifts dovetail with a transformation in tech giants’ outward politics: from reputed bastions of liberal bias and guardians of election integrity to eager supplicants before a mercurial president.

Executives such as Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos took pride of place at Trump’s second inauguration, while Palantir CEO Alex Karp reportedly donated $1 million to the inauguration fund. Not to mention the parade of tech barons (including from Palantir) who reportedly attended Trump’s glitzy fundraising dinner for a new White House ballroom last week.

‘Code-switching’ in pursuit of funds

Watson’s “green to guns pipeline” offers a vivid example of the sea change.

Explicitly defense- and intelligence-focused companies like Anduril and Palantir were once unusual in Silicon Valley. Though the Internet itself grew out of U.S. military research, by the Noughties there was a strong strain of civil libertarianism that disincentivized dances with Uncle Sam.

But then came the surveillance disclosures of the early 2010s, revealing how U.S. spies had exploited Big Tech’s systems to gather emails, phone calls, webcam images and more from millions of people without a warrant through programs such as PRISM.

These companies had been legally compelled to participate, had often tried to resist, and in some cases claimed not even to have known about it. Yet they were caught in the backlash anyway.

That experience embittered a generation of tech leaders against Washington. As recently as 2018, Google was forced to abandon a high-profile Pentagon contract after employees revolted, part of a broader wave of worker activism across tech giants.

Idealistic young techies flocked instead to companies with peaceful missions, not least those on a quest to tackle the climate crisis.

This was also the age of ZIRP – “zero interest rate policy” – in which the rock-bottom price of borrowing money made it much more viable to spend billions developing new technologies that would not be profitable for years.

“Ten years ago, green tech had a glow about it. It was a very optimistic moment,” says A.J. Kantor, a former Tesla manager and nuclear fusion entrepreneur who consults with companies trying to build hardware-intensive businesses.

“There’s still, I think, a lot of virtue that people see in working in that space. But where they see virtue is not necessarily where they now see opportunity, or money.”

By 2023, rising interest rates had devastated the tech sector. According to one dissident Google employee, who goes by the alias “Jam”, mass layoffs at the tech giant also emboldened the company to suppress its internal critics and push forward with military contracts.

“I saw [company leadership] taking the mask off slowly, and when Trump was elected I saw the mask fall off a lot quicker,” Jam says. (Google did not respond to a request for comment from The Independent.)

Now green tech founders are adapting as best they can, shifting their rhetoric or engaging in what has become known in the field as “greenhushing”.

South 8, a San Diego battery maker, initially planned to sell mainly to EV makers and utility companies, but have ended up signing a contract with the U.S. Army, Axios reported last October. One company which made jet fuel with a lower carbon footprint previously stated that it “exists to solve one problem: climate change”. Now those words are gone from its website, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Watson, a longtime green tech investor who is now head of commercial affairs at electric air cargo start-up Aerolane, is scathing about the ideological pirouettes of some VCs. But he’s deeply sympathetic to fellow start-up founders as they scramble to keep their dreams alive.

“They’re code-switching,” Watson says. “In the Biden administration, batteries were about powering an all-electric future. In the Trump administration, batteries are about ensuring that the warfighter has the most sustainable micro-grid to power their equipment in forward-deployed locations…

“I don’t critique them at all, because they’re just trying to bring their technology to market and give it the best chance of success.”

Moreover, both Watson and Kantor point out that there is actually plenty of material crossover between green tech and defense tech. Both require large investments in physical infrastructure with long set-up times, which takes a skillset quite distinct from that of pure software businesses.

Kantor even argues that green tech growth helped fuel the defense tech boom, by getting investors acquainted with this kind of work.

Many green technologies are dual-use, too. Gasoline can be an explosive liability in wartime, so the Pentagon has plenty of need for batteries and solar panels. Even before the election, the Defense Department — now rebranded the Department of War by the Trump administration — had contracted with lab-grown meat companies (to fend against food supply chain disruption); nautical sail-drone makers (to surveil Iran); and geothermal energy providers (to power distant bases).

“We’re profoundly lucky to have a pretty purple mission, as we call it,” says Grant of Magrathea, which has been working with the Defense Department for two and a half years. “That’s not true for other companies.

“I think there’s a lot of head in the sand with pure-play climate folks; a lot of denial. I think there’s going to be a lot of wound-down companies, failed funds, and sometimes people are just delaying the inevitable.”

Which, he adds mournfully, “is what you would do. I mean, they’re doing their jobs.”

‘We’ve seen the future of conflict, and we are behind’

Beneath the surface of all this is a much longer-term transformation that transcends partisan politics, dating back at least as far as Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

When the U.S. had invaded Iraq eleven years earlier, it was unparalleled on military firepower and technology, and its “war on terror” was a highly asymmetric conflict against lightly armed insurgents across the entire globe.

Yet with the start of Russia’s undeclared dirty war against Ukraine, the U.S. inexorably began being dragged into what scholars call “great power competition.” Today, all-seeing drones have unexpectedly turned Ukraine’s battlefields into a merciless robotic killzone, leaving U.S. military strategists racing to catch up.

Meanwhile, China’s high-tech industries have advanced rapidly, and now rival or beat the U.S. in futuristic fields such as hypersonic missiles, drone warfare, and quantum digital communications. Hamas’s surprise invasion of Israel, and Israel’s destruction of Gaza in response, also pulled the U.S. into a multi-sided Middle Eastern war.

“We’ve seen the future of conflict, and we are behind,” Kirsten Bartok Touw, a former DoD adviser and veteran defense tech investor, told The Independent.

“Five to seven years ago, we all believed we had the best technology in the world. There is a little bit of a humbling that maybe we didn’t invest enough in certain capabilities, and we need to catch up.”

Wary of losing its military dominance, the U.S. government has been working hard to deepen its tech industry ties. Even putting ethics aside, Kantor says many tech leaders traditionally considered the federal government a poor client, moving at glacial pace and subject to the whims of Congress.

Now, through groups like the CIA’s arm’s-length investment fund In-Q-Tel and the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit, that has finally changed. Projects funded through one or the other body include undersea drones, photon-based GPS-free navigation systems, wearable health monitors for pilots, satellites that spot other satellites, and advanced personal sensors for ground soldiers.

To Gregory Bernstein, CEO of the New Industrial Corporation and co-founder of the Reindustrialize conference, it’s part of a bigger project of nationwide industrial renaissance, marshaling both military and civilian tech to preserve the American way of life.

“We’re in an existential and generational grudge match with the Chinese Communist Party,” Bernstein told The Independent. “Reindustrialization is about rethinking the way all our societies interact, because… we are dependent on countries that want to do us harm.”

He adds that for him and an increasing number of founders, this too is an idealistic, epochal mission, on par with stopping climate change. “I actually think it’s totally non-partisan. It’s above politics,” he says.

Despite Trump’s antipathy, there is also a growing wing of tech and political leaders who see decarbonization as itself critical to national security. Even aside from the chaos that climate change will sow, think how many wars the world has been dragged into by the inky demon of petroleum.

“There’s nothing that says that you can’t care about climate and defense at the same time,” says Grant, who has been a “huge Russia hawk, and a China hawk” since 2014.

Whether Trump himself will aid these plans or impede them is open to question. Beyond his war on wind and slashing of climate funding, many experts doubt his tariffs will trigger any industrial renewal. He also makes a divisive figurehead for the defense of democracy, given his open admiration for autocratic leaders, repeated calls for his political opponents to be arrested or executed, and refusal to accept the results of the 2020 election.

“There’s no doubt in my mind at this point that Trump does not intend to relinquish power, and he has built an alliance with a lot of tech billionaires,” says Jam, the Google activist. “It’s the power of knowing your citizens better than they know themselves. The kind of authoritarianism [that] can create will be incredibly difficult to get rid of.”

To Alex Grant, whatever happens next, the pullback from climate tech is a source of sorrow.

“I was really encouraged by the end of the ZIRP era, when it seemed like climate change was finally gonna get solved,” he says. “Because I believe that climate change was caused by humans. And I would like to try to stop it! I would like to try to not just throw up my hands.

“That doesn’t mean that working on defense is not important. It’s actually very important… but I can still mourn the loss of the apparent commitment to tackle climate, while working on a different mission.”