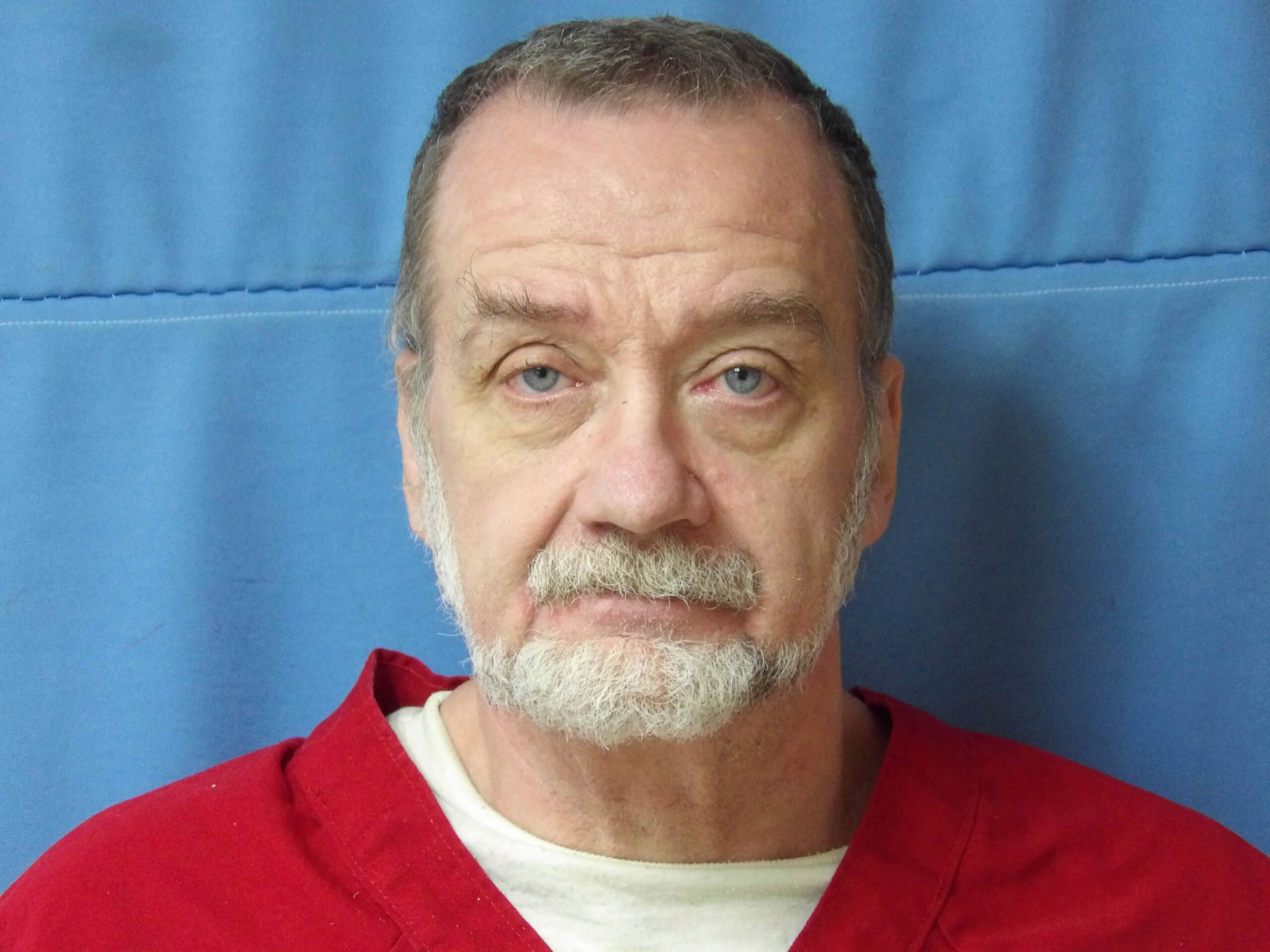

A Mississippi man, Charles Crawford, 59, was executed on Wednesday for the 1993 kidnapping, rape, and murder of a 20-year-old community college student.

He was pronounced dead at 6:15 p.m. following a lethal injection at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman. Crawford had spent over 30 years on death row.

His execution follows that of Mississippi’s longest-serving inmate amid a national increase in capital punishment. In his final statement, Crawford said: “To my family, I love you. I’m at peace. I’ve got God’s peace,” adding, “I’ll be in heaven.”

He also addressed Ray’s family, saying, “To the victim’s family, true closure and true peace, you cannot reach that without God.”

The execution got underway at 6:01 p.m. and Crawford could be seen taking deep breaths. Five minutes later, he was declared unconscious. At 6:08 p.m., his breathing became slower and shallower and his mouth quivered. A minute later, he took a deep breath and then his chest appeared to stop moving.

Crawford was convicted of abducting Kristy Ray from her parents’ home in northern Mississippi’s Tippah County on January 29, 1993. According to court records, when Ray’s mother came home, her daughter’s car was gone and a handwritten ransom note had been left on the table.

On the same day, a different ransom note, made from magazine cutouts and concerning a woman named Jennifer, was found in the attic of Crawford’s former father-in-law. The note was turned over to law enforcement, who began searching for Crawford. He was arrested a day later and said he was returning from a hunting trip.

He later told authorities he blacked out and did not recall killing Ray.

At the time of that arrest, Crawford was days away from going to trial on a separate assault charge. The trial stemmed from an attack in 1991 in which Crawford was accused of raping a 17-year-old girl and hitting her friend with a hammer.

Despite his assertions that he had experienced blackouts and did not remember committing either the rape or the hammer attack, Crawford was found guilty of both charges in two separate trials.

His prior rape conviction was considered an “aggravating circumstance” by jurors in Crawford’s capital murder trial, paving the way for his death sentence.

Over the past three decades, Crawford tried unsuccessfully to overturn his death sentence.

His lawyers had appealed to the Supreme Court, but in an order issued minutes before the execution was scheduled to take place, the high court declined without explanation to stop it. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a dissent that was joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The appeal alleged that Crawford’s lawyers admitted his guilt in the capital murder trial and pursued an insanity defense despite Crawford’s repeated objections.

“It’s almost like he didn’t even get the chance to have innocent or guilty matter because his attorney just overrode his wishes from the outset,” said Krissy Nobile, the director of the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Relief, who represented Crawford.

Sotomayor in her dissent noted that a 2018 ruling by the high court held that lawyers cannot override a defendant’s explicit and unequivocal decision not to admit guilt at trial. Under that decision, Crawford could have proven that his Sixth Amendment rights were violated and would likely be entitled to a new trial because his lawyers did just that, she wrote.

But Crawford’s convictions became final before that case was decided, and the court “has not squarely resolved” whether the 2018 ruling is retroactive and applies in postconviction proceedings, Sotomayor wrote.

“The Court refuses to resolve that question, even though a man’s life is in the balance,” she wrote.

The Mississippi Supreme Court had dismissed the argument in September, writing that Crawford should have brought the appeal sooner and did not present adequate reasoning why the Supreme Court ruling should be retroactive.

After the Mississippi Supreme Court set his execution date in September, Nobile said Crawford expressed both disappointment and resolution. Nobile characterized Crawford as a respected, uplifting presence on death row. She said he worked inside the prison and advocated for other inmates.

Marc McClure, the chief superintendent of operations for the Mississippi Department of Corrections, said during a press conference that Crawford visited with his family and a preacher Wednesday afternoon.

The Associated Press made multiple attempts to contact Ray’s relatives, but did not receive a response. Crawford also did not return requests for comment.

The lethal injection was the third in two days in the U.S. after executions Tuesday in Florida and Missouri. A total of 38 men have died by court-ordered execution so far this year in the United States.

In Florida, Samuel Lee Smithers, 72, was put to death for the 1996 killings of two women whose bodies were found in a rural pond. In Missouri, Lance Shockley was executed for fatally shooting a state trooper in 2005.

There are six more executions scheduled to take place in 2025, the next being that of Richard Djerf, who was convicted of killing four members of a family in Arizona over 30 years ago.