A bullish Trump fresh from his Middle East victory won’t scare Russia with missiles – Putin has shown he is perfectly willing to match escalation with escalation

Whether or not the “Trump Peace” in Gaza holds, for the moment, the US President clearly sees himself as on a roll. Given that this deal required his use of America’s considerable heft to strong-arm Israel, Palestinians and Arab states alike into compromises, he may be tempted to adopt a stronger line with Russia – but Vladimir Putin is signalling that he is willing to push back.

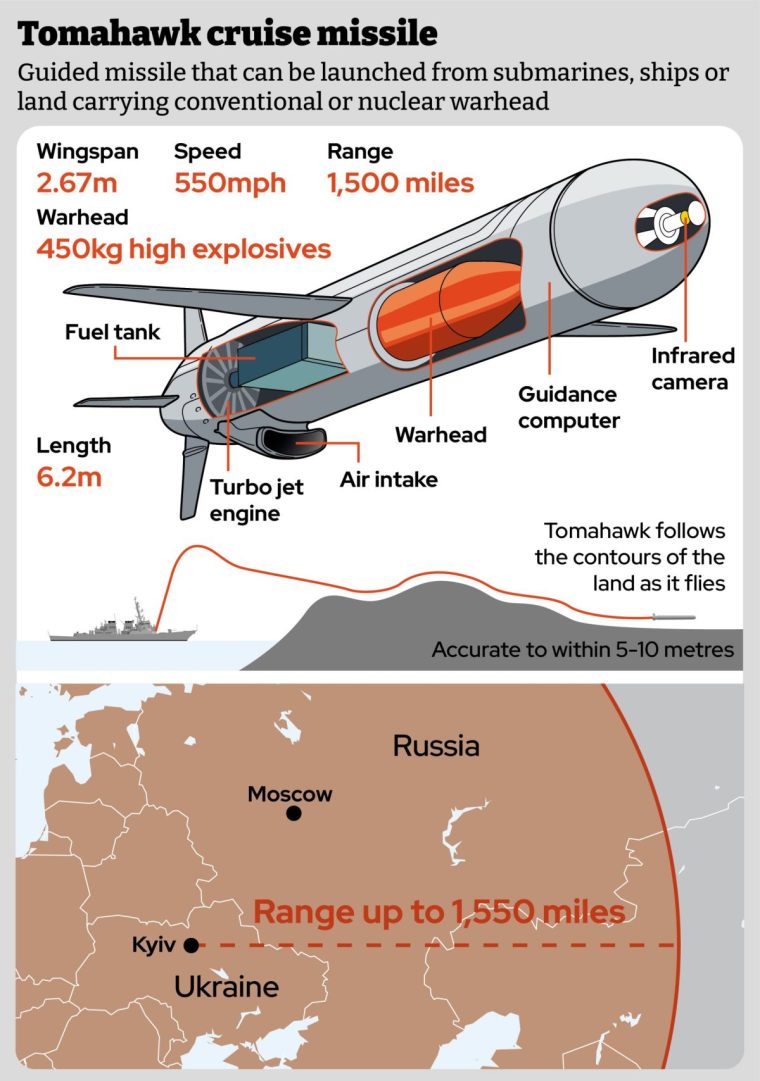

Although Donald Trump has essentially backed away from providing material aid for Kyiv – instead, he is willing to sell Europe weapons to transfer to Ukraine – it has recently been admitted that Kyiv’s successful campaign of long-range strikes against Russian oil facilities was facilitated by detailed targeting data that the Americans provided (something Moscow had long claimed). Trump also claims that he has “sort of made a decision” to let the Ukrainians have long-range Tomahawk cruise missiles.

He is, of course, notoriously fickle and there are doubts over the Tomahawks, because not only do the Ukrainians currently lack the systems to launch them, but the US military is eager to rebuild its own stocks. Nonetheless, it does hint that a bullish Trump, fresh from what he sees as his triumph in the Middle East, and by all accounts fully reconciled with Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, is contemplating threatening Russia with the stick, after the failures of his offers of carrots such as sanctions relief.

However, Putin shows no signs of being cowed. As one British diplomat noted to me, “Israel gets more than $3bn [£2.3bn] a year in defence aid from Washington, and that gives Trump the kind of leverage he lacks with Russia”. Indeed, Putin has been signalling both to Europe and the US that he is perfectly willing to match escalation with escalation.

The recent, sudden spate of alleged Russian drone intrusions, that just as suddenly ended, was presumably a warning about the extent to which Moscow could bring chaos without any direct military action.

Meanwhile, the law on Russian reservists has just been amended to allow the government to deploy them abroad without having formally to declare war or mobilise. Although this is unlikely to generate substantial extra forces without a full-scale mobilisation wave – which would be both unpopular and disruptive – along with measures to scale up the level of conscription, this is a signal that, if push comes to shove, Russia could find a lot more troops to throw into the war.

At this stage, both Trump and Putin seem essentially to be posturing. Trump may still cling to the hope of getting next year’s Nobel Peace Prize by also clinching a deal over Ukraine.

Yet with his navy currently taking potshots at alleged drug boats off Venezuela, his trade relations with China suddenly taking a turn for the worse over rare earth minerals, and the Gaza deal likely to be fragile and requiring more resources and attention, how far is he going to be willing to go?

Neither side really seems to want to up the ante at this stage, and certainly there is no danger of direct conflict between Russia and Nato or the US. When leaders begin to threaten and paint themselves into corners, though, there is always a risk is of accidental escalation.

Dr Mark Galeotti’s latest book, the revised and updated edition of his We Need to Talk about Putin, will be published by Penguin in November