The autobiography of celebrated British photojournalist Martin Parr has been slow to materialise. It’s not hard to work out why. Parr is a man of few words, as I discovered for myself, having failed to heed the cacophony of warning bells occasioned by his co-author Wendy Jones’s admission that she gave up on the book for 15 years for this reason.

There’s a sort of garrulousness to Parr’s photographs of the British public at leisure that can mislead you into thinking he’s going to be good for a chat. Surely you have to be a pretty upfront sort of person to take the pictures he does – so often close encounters with expanses of sunburnt flesh, beer guts and screaming children. There’s the man sunbathing on Eastbourne beach from Parr’s Think of England project, in which a great deal of well-bronzed flesh is made all the more invasively intimate by the sole of the foot – and the big toe – right in your face. Surely just as daunting, in its own way, was the Young Conservatives Ball, in the peak Thatcher year of 1988.

It seems not. “It’s just something you get used to,” the 73-year-old says, when I suggest that pointing a fairly large camera at people takes a bit of nerve. “You try and use body language to disguise [what you’re doing] sometimes, and if there’s a lot of people, then no one really notices.”

Parr and his wife Susie live in Bristol, but we meet in his agent’s office in London just around the corner from the Barbican, the capital’s famous Brutalist housing estate and cultural complex. Parr has a flat upstairs, a useful base for trips to London, dominated on this occasion by book signings and promotional events.

In marked contrast to the scathing school report that gives Utterly Lazy and Inattentive: Martin Parr in Words and Pictures its title, Parr is disarmingly focused. There’s no small talk, and our interview is dispatched with such speed that I’m still out of breath from climbing the stairs as I head back down them.

Parr’s tendency to reply “quickly and briskly” was what made Jones think their book wouldn’t work out – and she mothballed the project, concluding that “nearly all of Martin is in his pictures, not words”. Eventually she went back to him, suggesting that he told his story by talking to her about his chosen pictures. “He said yes, because Martin is someone who says yes,” she explains with enigmatic reserve in the book’s introduction.

The book is a chronological journey through 150 photographs, each one accompanied by a commentary from Parr, as recorded and transcribed by Jones. Beginning with his birth on 23 May 1952, the book spans almost 70 years of taking pictures. “A wonderful life with photography,” he tells Jones, in which he has experienced the revolutionary shift from analogue to digital. “I’ve got a lot older.”

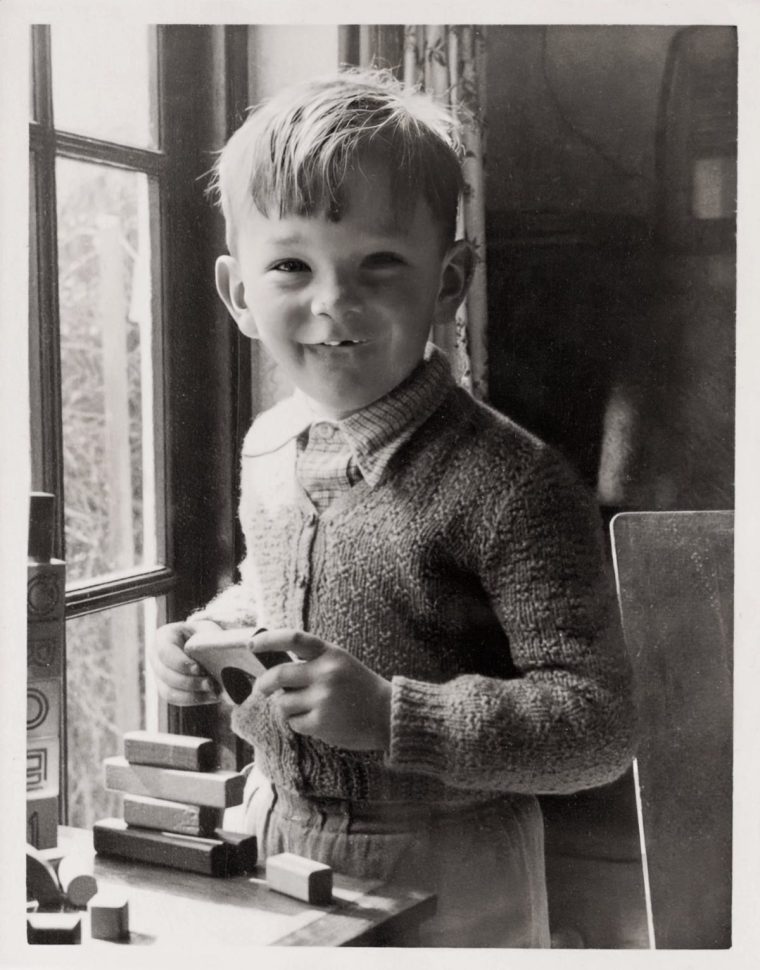

Naturally enough, the earliest photographs are black and white family pictures, the first of which is of the five-year-old Parr and a pile of wooden bricks. Like all of them, it is beautifully composed, with areas of deep shadow, contrasting with highlights that precisely define his knuckles, the texture of his cardigan, and the edge of a chair back.

It was probably taken by Parr’s grandfather George Parr, and the care with which it has been composed, printed and kept for posterity sets it apart from its equivalents today – which while likely to number the many thousands, all too often languish in the cloud, reduced to the unfriendly anonymity of an automatically generated file number. “Everyone’s got an iPhone or a smartphone now,” says Parr. “God knows what happens to all these images. Do they get downloaded? Do they get deleted? Who knows?”

Born in 1952, in Epsom, Surrey, Parr was brought up at a time when photographs were more consequential than they are today – not quite a luxury item, perhaps, but almost. He’s not nostalgic though – not in terms of photography anyway – and switched modes with alacrity, first to colour and then to digital. “Previously, I had to change film every 10 shots. Now I change card every 500,” he says, when asked how digital technology has changed his practice.

Changing to colour in 1982 was far more momentous, the fulfilment of an ambition seeded a decade before when he was a photography student at Manchester Polytechnic. He’d had a summer job as a “colour walkie” at the now defunct holiday park of Butlin’s Filey, taking pictures of campers in the tropical paradise of its famous Beachcomber Bar.

Much as he enjoyed the results, his first photographs of another beach – New Brighton, on the Wirral – taken in 1979, were still black and white. “I kept working in black and white partly because colour photography wasn’t taken seriously in the UK,” he explains in the book. “It was regarded as commercial and trivial, used for family snapshots because you could get cheap colour cameras.”

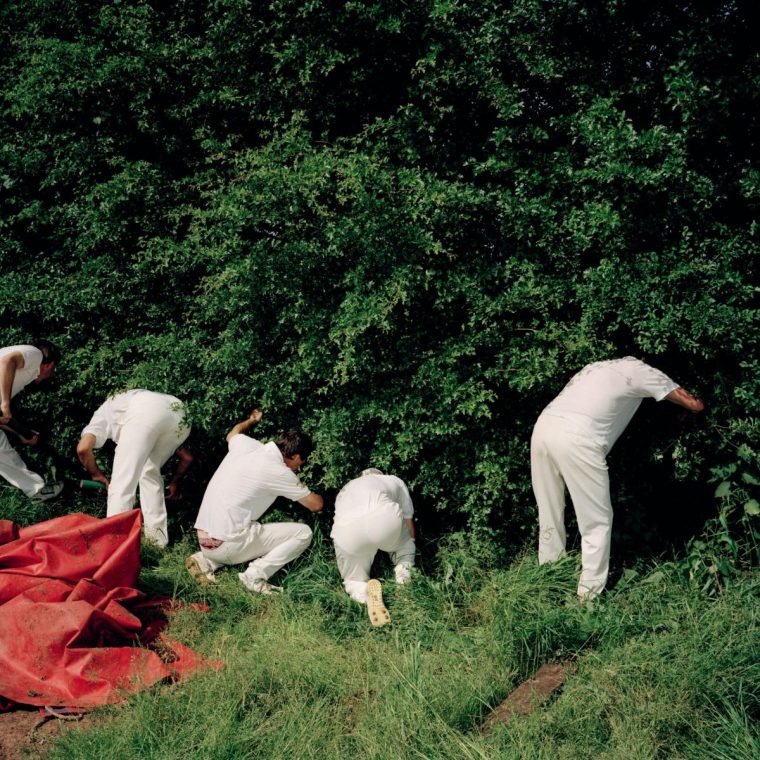

But by the late 70s, Parr had seen the work of American photographers like Stephen Shore and William Egglestone, and realised that serious photography could be done in colour. The transformation was immediate. Suddenly Martin Parr was taking Martin Parr pictures, the colour, and the larger format, bringing immediacy, intimacy, and a gravitas that somehow remains even as he catches people at moments of indignity, as in his 2017 picture in his Great British Seaside series in which beachgoers in Clacton-on-Sea scrabble for shelter under parasols and picnic blankets.

The picture he has chosen to represent his new era of colour is from his celebrated book and exhibition The Last Resort, published in 1986. It shows a family eating fish and chips on an unlovely bench at New Brighton, an overflowing bin in front of them.

Nobody had ever done anything quite like it before, and it divided opinion, with some critics offended by what they felt was the cynical judgement of the working classes by a middle-class outsider. It is an interpretation of Parr’s work that has never entirely gone away and for a time it extended to the hallowed headquarters of the Magnum photo agency, where opposition to Parr being made a full member was led by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Philip Jones Griffiths. In a now infamous fax to fellow Magnum members, Jones Griffiths described Parr’s “penchant for kicking the victims of Tory violence”, casting him as the “dedicated enemy of everything I believe in and, I trust, what Magnum still believes in”.

Although, as Parr points out with some energy, he became president of Magnum between 2013 and 2017, the spat still rankles. “Given that you probably haven’t got more than 2,000 words, it’s a bit of an indulgence to start talking about that too much,” he says tartly, when I venture there.

For all that, it is Parr’s apparently unwavering confidence in his own vision that has made his work so distinctive, appealing to younger generations of photographers who he supports via the Martin Parr Foundation, and a roster of commercial clients, including Vogue.

I wonder if, as a young photographer, he ever felt tempted to cultivate a more glamorous image? “Not, really no – I just told it as it was,” he says, making me think that perhaps he’d slightly misunderstood the question. In hindsight, it seems clear that he considers his presentation of himself, and his photographs, as an expression of his view of the world as being related and equally straightforward.

Still, the photographs don’t just happen. “There’s a documentary element to recording things which are potentially interesting for society, but then you’re also trying to take a good picture, an iconic picture, which is one that will sell and be used again and again. They’re very elusive.”

He was 15 the first time he took what he knew to be a very good picture. “It’s A Horse, an Old Lady, Some Trees, taken in the Yorkshire Dales. I was excited. I thought, this is something else, this is interesting. There’s something about it that works – I can’t explain good photos.”

A cancer diagnosis in 2021 has affected Parr’s mobility among other things, though not his appetite for photography: “It’s made me work harder, this year in particular. I know my days are coming to an end, so I’m out there taking pictures.” He’s not exaggerating: towards the end of the book there’s a selfie with the paramedics who took him to hospital, where a stomach operation revealed that he has myeloma (a type of blood cancer). “They called it ‘nodules on the spine’,” he explains in his book. “And when they say that it means it’s cancer.”

Along with trips to Rome, New York, and to a local iftar festival in Bristol during Ramadan, Parr has ticked off another “bucket list” project – photographing the Queen’s Garden Party. It’s his way of saying that in 2022 he was awarded a CBE, an occasion recorded in his book with his daughter’s snap of him and Susie. It’s a family snapshot, with the obligatory missing feet, and yet it fits perfectly into an account of one man’s life that is also a history of Britain over the past seven decades.

Utterly Lazy and Inattentive: Martin Parr in Words and Pictures (Penguin, £30) is out now