The UK should be reluctant to put troops on the ground in Gaza, experts tell The i Paper

The former head of the British Army has warned against putting UK troops on the ground in Gaza as part of an international peacekeeping force.

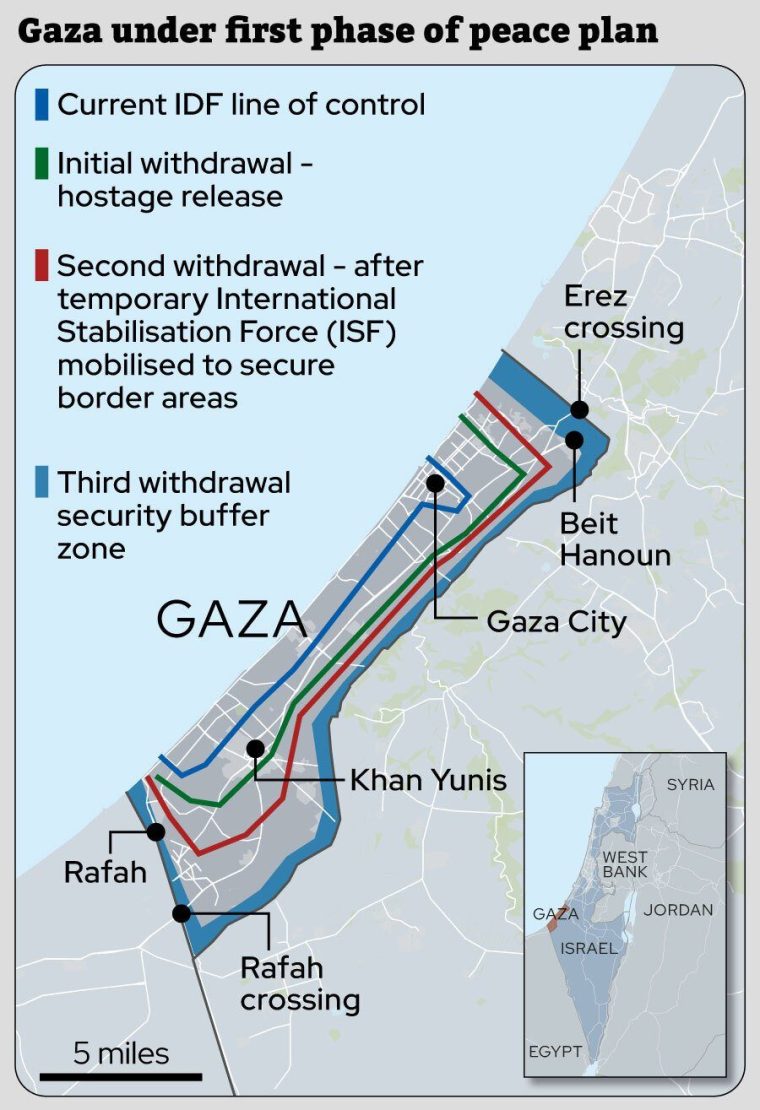

On Thursday, Israel and Hamas agreed to the first phase of a 20-point peace plan unveiled by Donald Trump, which is designed to pause fighting and secure the release of the hostages in exchange for Palestinian prisoners being held by Israel.

Shortly after, the US said it had moved 200 troops already based in the Middle East to Israel to help support and monitor the ceasefire deal.

This has raised questions over other nations’ involvement.

General Lord Richard Dannatt, former head of the British Army, warned against the deployment of British troops to the Gaza Strip, telling The i Paper: “I think we should be very cautious about putting British boots on the ground in Gaza.”

The Ministry of Defence is not currently considering any plans for a UK contribution to a Gaza peacekeeping force, The i Paper understands, with no meetings held on the issue so far. However, insiders said this could change as the situation develops.

The UK and France have previously expressed support for “the deployment of a temporary international stabilisation mission” in Gaza under “the aegis of the United Nations”, noting “the readiness expressed by some member states to contribute in troops”.

The suggestion was made in a declaration crafted by France and Saudi Arabia at a special UN conference in July, and was backed by 142 countries.

Dannatt said that “it looks as if US Central Command will coordinate the operation but the presence on the ground will come from troops provided by neighbouring countries. On that basis there is no role for the United Kingdom.”

He also pointed to lingering controversy over Britain’s mandate for Palestine, obtained after the First World War, which endowed the UK with the power to govern the territory.

“As Britain formerly held the mandate for Palestine and being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, the UK Government would have to consider very carefully whether or not to participate in a peacekeeping mission in Gaza,” Dannatt said. “It is very early days to comment further but this would be a key issue for our government to consider.”

Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper told the BBC that there are “no plans” to send troops but there is “an immediate proposal for the US to lead what is effectively like a monitoring process.”

Cooper said that US troops will oversee the hostage release process and make sure “this first stage is implemented, getting the aid in place.

“But they have also made very clear that they expect the troops on the ground to be provided by neighbouring states, and that is something that we do expect to happen.”

Richard Caplan, professor of international relations at the University of Oxford, also cast doubt on the prospect of British troops being deployed in Gaza.

He said: “Britain’s colonial heritage looms large in the region — the Balfour Declaration, the British Mandate, the Suez debacle — such that Britain’s return as a military force might not be an altogether reassuring presence.”

But Professor Roger Mac Ginty of Durham University’s School of Government and International Affairs told The i Paper that British soldiers could eventually “play numerous technical roles from ceasefire monitoring and verifying the decommissioning of weapons to securing humanitarian aid routes and training Palestinian forces.”

Even so, he said the Government “is likely to be wary of open-ended commitments. The experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan were searing, and without a longer-term political agreement the danger is that it becomes a zombie mission destined to continue in perpetuity. “

A security role

Vincent Fean, a former British Consul General to Jerusalem between 2010 and 2014 and current trustee of charity the Britain Palestine Project, said that the UK already has a small training team in Ramallah, of long standing.

The British Support Team (BST) has provided expertise, project management and mentoring to the Palestinian Authority Security Forces since 2006, as part of a US-led effort in the West Bank.

“It is too soon to know what role Europe, including the UK, would play beyond providing training,” Fean said.

Mats Berdal, professor of security and development at King’s College London, told The i Paper the UK could play a similar role in Gaza to what it played in Sierra Leone after the civil war there, which lasted from 1991 to 2002.

The UK worked in partnership with the Government of Sierra Leone to help rebuild its police, military and security sectors after the war as part of the “Security Sector Reform” programme.

“The UK played a constructive role, with a small-scale mission, in supporting Security Sector Reform in Sierra Leone after the war there ended, but the context is of course different,” Berdal said.

“I can imagine some kind of training role is possible” for the UK in Gaza as part of an international effort, Berdal added, but highlighted that a major constraint will be resources available to the British military.

“The British armed forces are fully committed on Russia and trying to rebuild security at home, so the resources are quite stretched.”