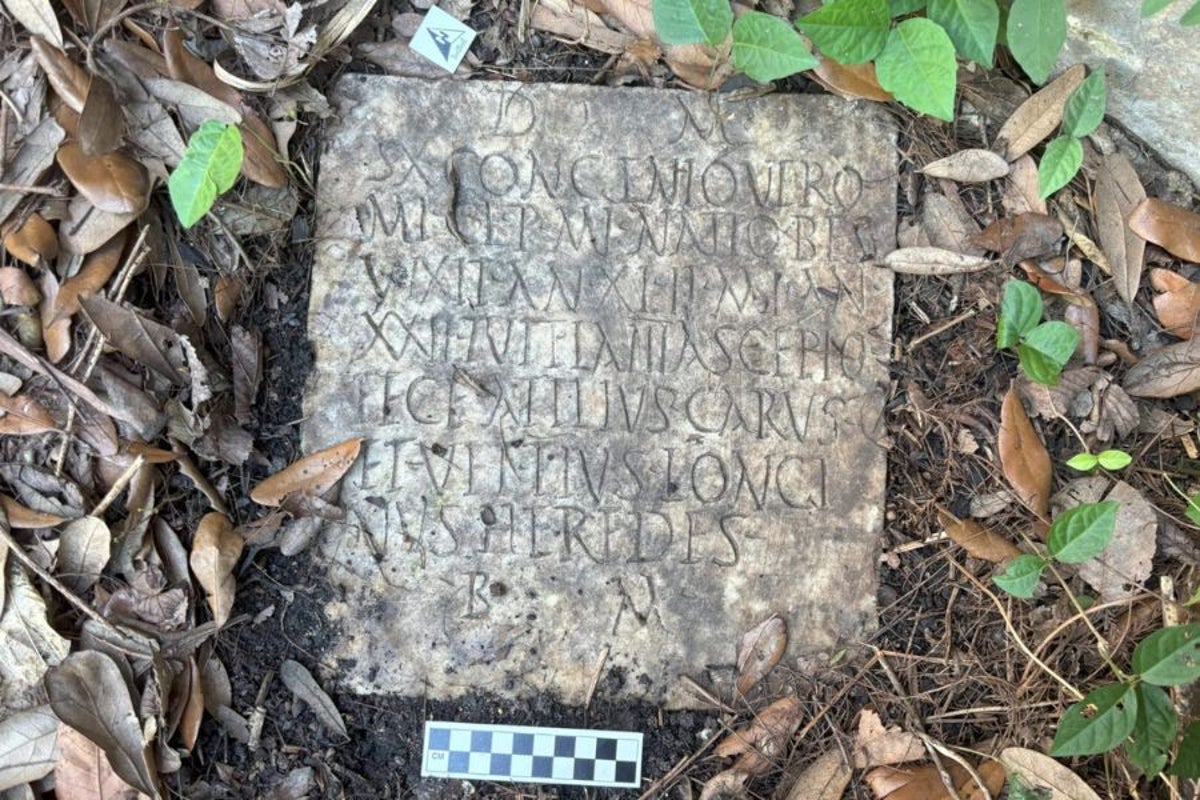

What started as a routine yard cleanup turned into an extraordinary archaeological discovery when a New Orleans couple unearthed a marble slab bearing an ancient Roman inscription.

Experts have confirmed that the slab is a tombstone dating to the 2nd century, sparking an international effort to return it to Italy, as well as raising questions about its journey to Louisiana.

In an interview with 11 Alive, Tulane classical studies professor Dr. Susann Lusnia said: “[The discovery caused that] shiver in your spine, and it’s just kind of like, “Oh my God this is, this is an actual Roman thing.”

The curious case started when Tulane University professor Dr. Daniella Santoro and her husband, Aaron Lorenz, discovered the stone beneath six years of overgrown vines at their historic home in the Carrollton neighborhood.

When Santoro noticed the marble slab was carved with ancient names and abbreviations, she contacted colleagues at the University of New Orleans and Tulane University for help.

Lusnia and UNO archaeologist Dr. Ryan Gray eagerly began examining the artifact. Gray sent photos of the tablet to Harald Stadler at the University of Innsbruck, who then shared them with his brother, a Latin instructor.

Both researchers independently identified the slab as a 2nd-century Roman tombstone for a Roman Imperial Navy sailor named Sextus Congenius Verus, matching one missing from a Civitavecchia, Italy, museum since it was bombed during World War II.

The stone must be formally returned to Italy, so Santoro turned it over to the FBI’s Art Crime Unit to begin the long process of repatriation.

How the tombstone ended up in New Orleans remains a mystery, however. Gray said it may have been sold by an antiques dealer, reused as a paving stone, or passed through other hands, as researchers continue to investigate.

“For me, this story reflects a wonderful intersection of a homeowner’s curiosity ultimately bringing to light something unexpected and historically significant,” Gray wrote in his Preservation Resource Center article.

Researchers also look into the property’s history to try and find a path for the tablet.

Archival records show that the home of Santoro and Lorenz belonged to the family of Frank and Selma Simon for most of the 1900s, Gray said.

After Frank died in 1945, his daughters retained the property until 1991, and Santoro and Lorenz purchased it in 2018. Frank worked at a wholesale shoe company, while his daughters largely worked in retail, meaning they were unlikely sources for the stone, according to Gray.

Initially, Santoro’s team considered a neighboring World War II Navy veteran as the possible person who brought the tombstone from Italy, but records confirmed he served only in the Pacific theater.

Lusnia eventually traveled to the city of museum of Civitavecchia to try and find an answer. The museum was heavily shelled allies during World War II, losing most of its collection in process. It did not reopen until 1970. It is likely, Gray wrote, “that the item was lost in the chaos after the war.”

Lusnia research indicated that U.S. troops did travel through the city and remained there for some time after Rome fell to allied troops in 1944. However, the group opted against examining the thousands of U.S. service records from the area for any links to New Orleans, given there was no guarantee of success.

Gray added that it was possible that the stone eventually ended up in the hands of an antique dealer, who sold it to a tourist after the war given the lack of restrictions in doing so at the time.

“While we may never know exactly how Sextus Congenius Verus’ tombstone ended up in New Orleans, we do know that the item is now safe, and it is on the path to being returned to where it can be properly displayed,” Gray said.

The stone remains in the U.S. for now, with a repatriation ceremony planned at the Italian museum next summer.