KHAN YUNIS – Gazans have a message for Donald Trump: We are asking him to be serious and complete his plan, stop the war and end the suffering.

The plan is not entirely good, but its goal is good: to stop the war in Gaza. We’re concerned about the seriousness of its implementation and are following the negotiations closely, hoping they will succeed this time.

The positive thing is Trump’s interest and insistence on stopping the war; what happens in the coming days will confirm the truth of what is being said in the media.

Do I trust him? No, he is crazy. You can’t predict what he will say or do. But the people of Gaza have been waiting for this plan since the beginning of the war. This plan is the dream of every citizen.

For two years, everyone has been asking me, “Are you alive?”

I answer, “Yes,” but mentally and psychologically, I have been dead since the war began.

First, I was displaced from my home and had to leave everything I loved behind. Next: pain, hunger, bombing, killing, and destruction.

In two years, I have not experienced one good moment.

I would need long books to describe every moment I have lived through. It’s an experience I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Missiles fall without anyone knowing who they will hit. Any movement requires extreme caution, fear of death and never returning to family.

Since the war began, I’ve made it a habit to inform my family of every move I make. I want them to know where I am, so that if they hear news of a bombing in the area, they’ll come to me.

I almost lost my life from trying to deliver my message to the world. I have been shot and fallen from up high.

I am traumatised and have nightmares that a bomb is about to explode next to me. At home, I imagine the ceiling falling on me. I try to stay in rooms facing the street so I may be rescued. The intensity of Israel’s bombing spares no one. None of us can consider ourselves survivors. If children don’t survive, how do we go on as adults?

Since the start of the war, we have been battling to obtain the necessities of life – water, food, medicine, and electricity, if possible. Every moment is a fight for survival. We wake up each day wondering if we have enough water. We share difficult tasks among members of the household. My 56-year-old father is severely depleted from carrying gallons of water long distances. I, too, suffered stomach and rib pain from carrying water. My father has spent a year travelling twice a day to a hospital to charge my phone and laptop so I can work as a journalist. I spend long hours in the street trying to get an internet signal to communicate with the outside world.

I never imagined I would wake up with nothing to eat, and only have one meal – breakfast, lunch, or dinner. I have an intolerance to beans, lentils and rice, but have to eat them to give me strength. I am often tired and unable to continue working, spending long hours sleeping, with little time for family. It is the hardest feeling, realising that our human rights are nonexistent, and that October 7 meant Gazans could be left to starve and die.

Displacement is like the soul leaving the body, leaving behind memories to enter an unknown, unstable reality, building a new life from scratch. Its costs have exhausted us, we have no money left, nothing for our future. The future is unknown in Gaza, the past destroyed, the present all suffering.

The past four months were the hardest I have lived through during the war. Every day, I am surprised to wake up alive.

I left my house with my mother, father and sisters on 21 May, fleeing the bombing and the army’s warning to eastern Khan Yunis – without looking back.

I did not say goodbye to my home, which replaced another that was demolished by Israeli bulldozers when I was eight years old.

I left that house, built with love and money from my work as a journalist, to save my sick mother.

We moved to Khan Yunis camp, west of the city, to a destroyed house that almost collapsed on us under intense bombing.

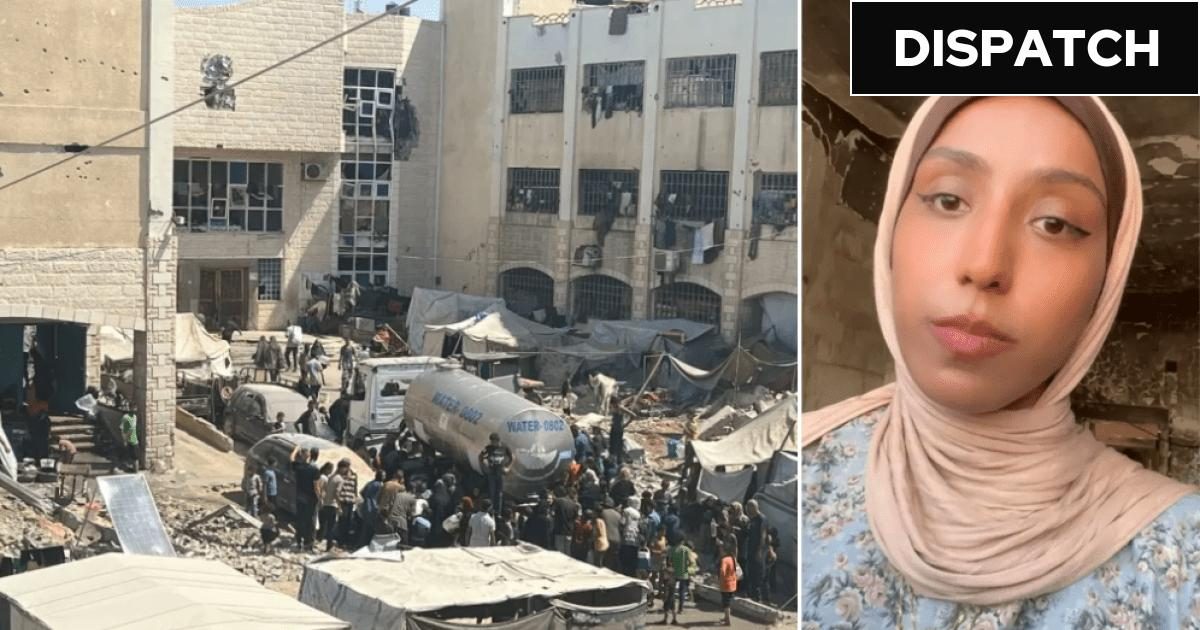

I lived on the streets for days until I found another home. I am still in the camp. Devastation surrounds me. Voices rise as a water truck arrives; everyone is thirsty, talking and screaming, desperate for the war to stop, but with little hope.

There is no safety or protection for a journalist in Gaza. Some people do not want me in their homes because journalists are being targeted. In August, my colleague Maryam was killed. It affected me greatly. I lost someone who loved her work and life in a direct attack in front of the world.

I have felt the responsibility of covering the war for 735 days. We, too, are citizens. We are hungry; we have families.

We long to tell the world that the war in Gaza has stopped. Instead, the situation is exploding; the city of Rafah and two-thirds of the city of Khan Yunis are red zones. Where will nearly a million citizens of Gaza be displaced?

A war unlike any other

I am a 30-year-old science teacher and journalist. I spent my childhood in the Khan Yunis refugee camp in the south of Gaza. My simple house was adjacent to an Israeli settlement. I lived eight years of hardship with Israeli soldiers storming homes every day to search for young people and arrest them.

I experienced tear gas bombs and the sounds of young people chanting for an end to the occupation and freedom for Palestine. On a dark night, when I was eight, the Israeli army bulldozed my house and we became homeless for two years, moving from one place to another, until we obtained a house with relief from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

This house was too small for a family of seven. My father, who worked as a mechanic and a driver earning $15 (£11) a day, lacked the time and funds to improve it. A good man, he barely provided for us.

My standard of living was modest, but I had great ambition. I studied in UNRWA refugee schools and then government schools. I’ve never forgotten the sight of my house in ruins in 2000, and the many photographers and journalists who documented that event.

I wondered if I could be like them. Years passed, and I held on to my desire to study and not marry, as the other girls in my family did. I was challenging my reality by becoming an educated girl – everyone wondered whether I would be able to do it.

I told my father, “Don’t worry, I will finish my studies and I will help you.”

Life became difficult after 2007, when I was at high school, and the blockade began. I studied hard to get into university. My mother gave up the small amount of money she had and said, “I want you to learn.” I finished my studies as a science teacher and started looking for work. This was difficult in 2013.

I gathered students in my area, east of Khan Yunis and offered lessons from 7am until 7pm. It was a tiring period. I began to develop my talents for writing and filmmaking, and in 2014, I began a career in journalism and teaching children at scientific educational centres.

I worked to help my siblings pay their college fees. Every two years, I upgraded the house. In 2019, I began working as a teacher in Gaza City to fund treatment for my mother, who had been suffering from spinal problems for years. I learned English and began working on documentaries.

Since 2008, I’ve lived through successive wars. Each one drained my energy and added to my negative feelings. I waited for any country that could stop these wars. When we survived, it was considered a chance to live again. But the October 2023 war was the harshest.

By 2019, I was finishing the house, making it suitable for my ageing parents. I lived four wonderful years, happy with the life I had made through willpower and determination.

In 2023, our house was completed. I hoped to travel outside Gaza to get treatment for my mother’s cartilage problem and help her walk. For three months my father lived with great joy and pride that I had kept my promise to him. Then came the shock of October 7.

An even more tragic story than the previous one began. Constant bombing, a siege leading to hunger and thirst, power outages, communications outages, and costs no one could afford.

I worked as a journalist from the first day of the war, covering the insane events as they unfolded. Once, homeless, I sat with my family in a hospital car park during a cold night. We faced constant news of lost friends, colleagues, and students. I felt deeply saddened by the loss of my students, who shared their dreams and ambitions with me. I lived the happiest days of my life with them at the Rosary Sisters School. Memories a thousand years could never bring back. This is a different kind of pain, a pain without death.

Working as a journalist means fighting to be heard by the world. I tried to overcome these hardships and provide strength and support to those around me, but when I was displaced from my home last May, I felt as if my soul had been ripped from my body.

I spent 12 years working hard and depriving myself to save money so I could have a beautiful home and provide my family with winter clothes and food during the famine.

I left my beloved home without thought, forced by the army to leave with my sick mother and a bag containing my devices, afraid that if I didn’t hurry, I could lose her.

I think constantly about my work and family, if I gave myself a moment to think about myself, I would lose my mind. I don’t know if I have another ten years of enthusiasm, ambition and energy, I feel helpless in front of everything happening around me. I am quiet, I wake up at night and my heart is sad, I often think that I will not survive this pain.

I was loyal, but the world was not loyal to me; it did not save me from this darkness. I am still the ambitious, optimistic girl who loves life, but I have become helpless.

I hope the world understands the meaning of peace, that it lives to spread it among people. I lost peace and safety and everything beautiful inside me. I want to return to the hopes of my childhood.