For Betty Parsons, the New York gallerist who backed Jackson Pollock when no one else would, painting was her refuge. Parallel to a remarkable career as one of the 20th century’s most intuitive talent spotters, she pursued her own art with commitment and passion over weekends spent at her studio in Southold, Long Island. “When I’m painting in my studio… I forget the gallery entirely,” she said.

Though honoured with a solo exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1968, until recently Parsons was destined to be remembered only for her eponymous gallery, which, at key moments between 1946 and her death in 1982, championed both the white male “giants” of abstract expressionism (Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still) and artists from less well-represented backgrounds and identities, including Agnes Martin and Barbara Chase-Riboud.

The De La Warr Pavilion’s survey, the first in Europe to be dedicated to Parsons, is a deserved celebration of Parsons the painter and sculptor. In it, her influences – from the artists she knew and admired to the natural world – are reflected and absorbed in work that often zings with the “sheer energy” of the show’s title.

The light-filled spaces and spectacular sea views of the art deco Pavilion are the ideal anchor for paintings whose twists and turns through abstraction never quite seem to relinquish representation, echoing the shifting vistas and light in the gallery.

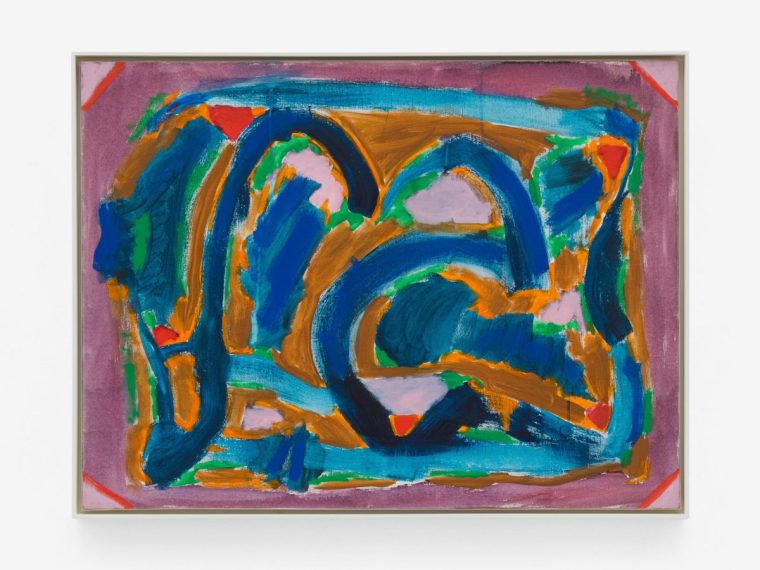

A tightly curated selection of around 50 works spanning 50 years, the exhibition is loosely chronological, and charts the broader shifts in Parsons’ style while tracking her tendency to return again and again to certain ideas. She oscillated between delicate, linear gestures and a robustly geometric style, but colour was always her guiding force, from the pink neon glow of Summer Fire (1959) to the vibrating complementary colours of St Simon (1952).

Though a weekend painter, Parsons was not a hobbyist – between 1923 and 1933 she trained as a sculptor in Paris with Rodin’s former pupil Antoine Bourdelle. But it was 1965 before she returned to sculpture, collecting pieces of discarded wood at Southold to assemble and paint, in totem-like and often absurd approximations of little men, a boat or a house.

The earliest works here are gouache on paper landscapes from the 1930s and 1940s in which her love of bold colour contrasts, distinct forms and calligraphic gestures – and Matisse – is already fully fledged in the rippling water, beautifully detailed houses and little boats of Rockport (1943).

There was a significant style shift in around 1950, just as abstract expressionism hit its peak. Parsons moved away from descriptive landscapes and instead isolates forms, setting them in fields of colour, often articulated by vigorous brushwork or by lines incised in wet paint with the wood of the brush, as in Bahamas (1950).

For a period in the 1950s and 1960s she settled on arrangements of forms in fields of colour, disrupted, as in Sand with Shapes (1964), by a ravaged-looking surface, or more often by lines incised in the paint. Curator Joseph Constable subtly equates this gesture to handwriting by including a 1966 work that incorporates one of her poems.

Associates, New York)

As the Sixties progressed, her paintings responded to the shift towards hard-edged abstraction, and it’s easy enough to look at her work, and spot strange disturbances of colour and surface that recall Clyfford Still, or the obsessive fields and borders of Rothko. Even so, Parsons was not imitating their styles – even less their preference for vast canvases – but processing them.

In transcendent evocations of light and space, and specific allusions to her seaside retreat and to world events, notably space travel, Parsons’ art is a form of journalling, assisted by a disciplined, meditative approach. “When I start painting a picture I try to become a blank and only let an emotion come into me,” she explained in 1968.

These are not the radical works of the artists she represented: her whimsical, and frankly childlike sculptures, and luscious colour combinations show a woman at play. “My studio is the biggest playroom on Long Island,” she said, revealing, perhaps, and hardly inconsequentially, the secret of her career as a groundbreaking gallerist.

Betty Parsons: Sheer Energy is showing at De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea until 18 January 2026