Placebo had only just released their debut single when David Bowie, forever ahead of the curve, invited them to support him on tour in early 1996. At the time, frontman Brian Molko didn’t think anything of it. “You’re a young, arrogant, sarcastic individual,” Molko says of himself. “You end up believing that’s where you’re supposed to be and that we deserved it. It’s not until I got distanced from the whole thing that I realised how much of an unbelievable opportunity it was, and how unusual.”

The relationship between Placebo and Bowie is one of the highlights – and certainly the heart – of This Search for Meaning, film-maker Oscar Sansom’s intimate, revealing documentary charting Placebo’s boundary-pushing 30-year existence. Bowie acted as friend and mentor to Molko, taking Placebo on the road for five years, collaborating on a reworked version of their second album’s title track, “Without You I’m Nothing”, and performing a T-Rex cover together at the 1999 Brit Awards. The rare and unseen footage of joint interviews and candid backstage moments shows the rapport and respect between them, Bowie cheekily holding court with gravitas and wisdom.

“The thing about David is that he was such a raconteur that sometimes you had to tell him to shut the f*** up – listen David, it’s my turn to talk,” Molko says. “But my memories are just conversations going on for hours and hours and hours, a very relaxed person who is genuinely interested in the people that he was talking to, very open. It was really, really lovely and very un-rock starry.”

Molko gets emotional talking about Bowie’s death. “I didn’t really realise the impact he had on me as a human being, as well as an artist, until he wasn’t there anymore,” he says, drifting off slightly. “And it hit me hard.”

The film is a keen reminder of just why Bowie became so enamoured with Placebo in the first place. There was the music, of course, an exciting, gothic amalgamation of glam, grunge and industrial, full of buzzsaw guitars, metallic sounds and Molko’s memorably nasal tones. But Placebo were a radical, dark and dangerous proposition for mid-90s Britain: with melodramatic, blackened songs of abuse, isolation and infatuation, they celebrated not just queerness but its seedier elements.

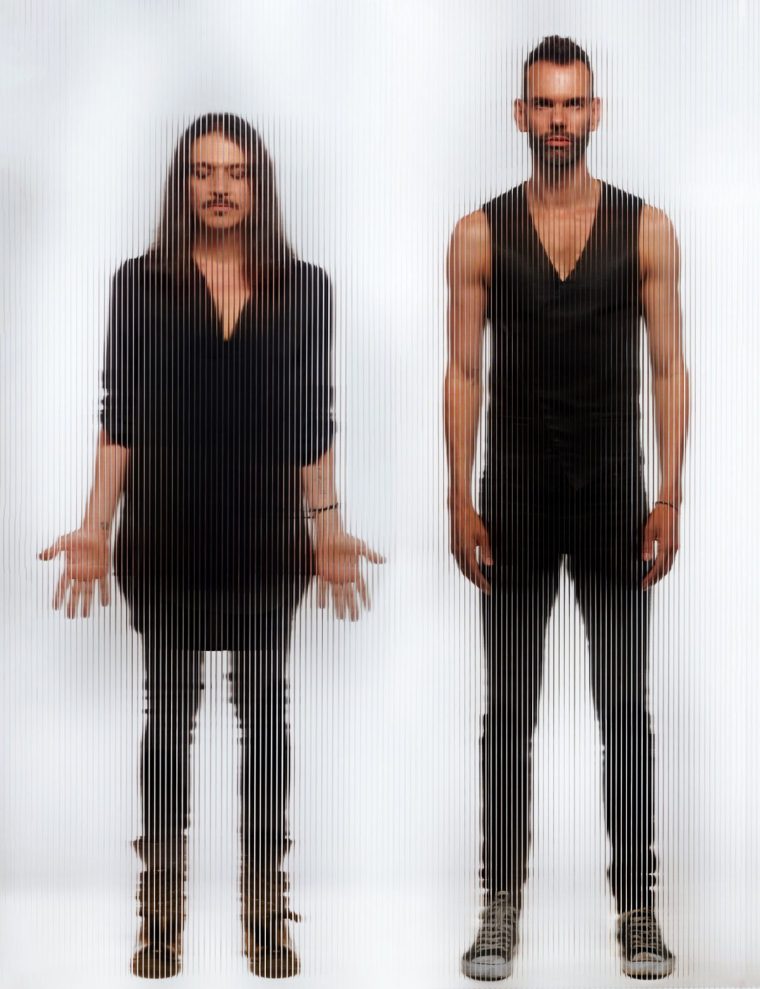

Along with former schoolfriend, founder, multi-instrumentalist and co-writer Stefan Olsdal (there have been three drummers along the way and Placebo are now officially a duo), Molko’s androgynous look – thick eyeliner, black lipstick, short dresses – carried a shock factor. “Our aesthetic had the idea of complete freedom and complete sexual freedom from these incarcerations of gender binaries.” It brought confusion, rabid devotion and outright hatred.

Success – three Top 10 singles between 1997 and 1998 – emboldened them. “We were wilfully provocative at times. If we felt that there was a certain hostility in the venue, before going on stage we put more make-up on and changed into a shorter dress. What was important to us was that it was a reaction, whether it was adoration or hatred. We fed off of those things equally. It felt like we were doing something right if half the room was in love with us and the other half wanted to kill us.”

Coincidence had it that Placebo’s self-titled 1996 debut arrived at the commercial height of Britpop, just after it had taken its loutish, lager-stained downturn; though formed in London, the Brussels-born, Luxembourg-raised Molko and Swedish Olsdal were genuine outsiders. Placebo’s performance of their gender binary-confronting signature tune “Nancy Boy” on Top of the Pops in January 1997 felt like a sexless alien crashlanding on Geezer Island. Good timing, or not?

“Probably yes, because we stood out like a sore thumb,” Molko says. “We certainly didn’t set out to be the antithesis to Britpop. The media kind of engendered that to give the whole thing context. But we were phenomenally disinterested in what was happening at the time. I didn’t think that Oasis were very good songwriters. This obsession with Britishness just didn’t really compute with us.”

But in their own strange way, Placebo did actually fit into the outrageous times. Molko was a spiky, knowingly sassy spokesman out for trouble; read old Placebo interviews and you’ll get carefree mouthy quotes about sex, drugs and gender, peppered with the sort of spicy bon mots that bands just don’t serve up anymore (“I feel like something being lined up to be fucked by Oscar Wilde, all 19th-century and renty.”)

Molko once famously claimed to have “left a trail of blood and spunk across Britain” after their first major tour. “Well, there’s a lot of bravado involved,” he says. “It’s a situation where it’s almost irresistible to not be outrageous and not provoke. And it didn’t do us that much of a disservice. But, you know, looking back, I would have preferred to have a little bit more of a filter.”

Now 54, Molko is naturally a more-guarded conversationalist (though he is currently charged with defamation in Italy for allegedly saying in Italian on stage in Turin that the country’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, is a “piece of sh*t, fascist, racist”). As seen in This Search for Meaning, honest self-reflection laced with high ideals is more his style. And the host of famous fans lining up in the film – Robbie Williams, Garbage’s Shirley Manson, Yungblud, Idles’ Joe Talbot, Self Esteem (aka Rebecca Lucy Taylor), Benedict Cumberbatch talking from the back of taxi – is testament to Molko’s cultural impact.

In a novel approach, interviewees are shot to look like they are being filmed unawares on CCTV. (Surveillance culture and big tech overreach are a bugbear of Molko’s, as well as a subject of later Placebo material.) The film features potent performances of atmospheric tracks from 2022’s return-to-form Never Let Me Go, their highest charting album in the UK, reaching No 3.

Molko says he wasn’t aware that Taylor and Talbot were such big fans, though Yungblud has performed with Placebo. His relationship with Williams, meanwhile, goes back to their respective 90s hedonistic days. “When we met we were very much going through a lot of the same issues, and found a real connection. Robbie’s a bit of a big brother to me. He’s an extremely kind individual.”

And, like Williams, Molko is prepared to show his scars in public. This Search for Meaning doesn’t shy away from the depths of his drug and alcohol abuse. Molko had to walk out of last year’s premiere in London during what he calls “the addiction section” using unearthed footage shot on VHS camera. There are passages showing Molko visibly worse for wear and out of control on tour; after he sabotages one gig with his incomprehensible ramblings, it cuts to backstage where a furious Olsdal barracks him for his behaviour.

“It was too close to home, really, to see it on such a such a big screen,” Molko says. “It’s a very uncomfortable moment in the film. So I had to step out. Stefan too.” He says that “between the 90s and 2000s there were quite a few moments like that”. But he wanted to show the “brutal honesty about what happened to us and what our lifestyles were like at a certain point”.

He says that for a while he did enjoy his excesses. “But the honeymoon period does wear off. People like to live vicariously through other people. And I think it’s worthwhile to show that it’s quite ugly at times, and it’s humiliating and it’s undignified, and it can have a really, really negative impact on all of your relationships.” He says that around 2007 they both decided to start living healthier lives.

In some ways Molko and Olsdal, though bound by their outsiderdom, are an oddly-matched duo. Olsdal is certainly more reserved; even physically, the beanpole Olsdal towers over the diminutive Molko. The film exposes moments when Olsdal seemed dissatisfied with life in Placebo.

“I think we’ve both at times questioned if Placebo has a future. We’ve had our moments. We’ve had tempestuous times,” Molko admits. “But we still love each other. As we’ve grown older, I think we appreciate each other as people more, and appreciate our differences and how we fill in the gaps with each other. And it’s when we fill the gaps that we become Placebo.”

They’re doing something right. Next year is the 30th anniversary of their electrifying debut album. “I don’t question it. I don’t necessarily understand it, either. I like the mystery, and I like the romance of it. To find that kind of songwriting partner, one hopes that it’s in the lineage of people like Morrissey and Marr. I think what we’ve achieved is something very, very precious.”

This Search for Meaning is out now on Blu-ray, DVD and CD