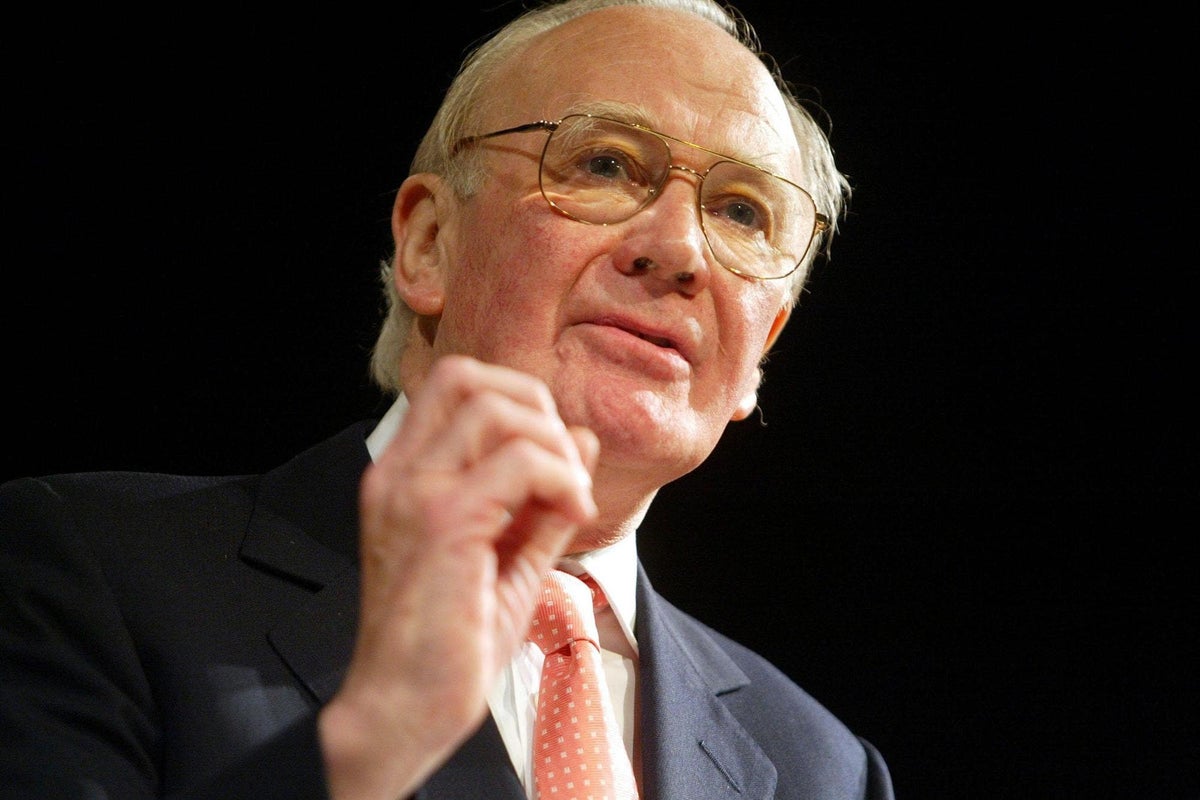

When Menzies Campbell was elected Liberal Democrat leader at the age of 64, his redoubtable wife Elspeth was heard bewailing “What are we doing? We should be retiring and sitting in front of the telly.”

It was an all-too-prescient remark: just 19 months later he was indeed “retired”, forced to resign after proving unable to shake off claims he was too old for the job.

It was an ignominious end for a politician who for more than a decade as his party’s foreign affairs spokesman had established himself as one of the most authoritative voices at Westminster, respected across the political spectrum.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq and its bloody aftermath, he was one of the most eloquent and effective critics of Tony Blair’s decision to join the American-led coalition to oust Saddam Hussein.

His performance, in partnership with the party’s charismatic leader Charles Kennedy, helped propel them to the best general election result of any Liberal party since the days of David Lloyd George.

While he was significantly older than his Labour and Conservative rivals when he became leader – the Tories’ David Cameron was just 39 – it was not just age which told against him.

With his upright, patrician air and immaculately tailored suits, he could appear like a figure from an earlier era, uncomfortable with the demands of the 24-hour news cycle for instant soundbites.

Having made his name in the rarefied field of foreign affairs, he struggled with the bearpit of Prime Minister’s Questions: his first attempt to take on Mr Blair was a fiasco from which he never truly recovered.

Despite his frustration at the incessant focus on his age – not helped by the “careless talk” of some other senior Lib Dems – he nevertheless accepted his ousting with characteristic good grace.

But then, for all his gravitas and clear sense of duty, he was in some ways an unlikely politician.

He once admitted his “real obsession” was sport: as a young man he was a top class sprinter, holding the British 100m record for seven years and competing in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

After athletics gave way to the law and a career as a barrister, he said his real ambition was to become a judge, describing himself as “a lawyer first, politician second”.

Walter Menzies “Ming” Campbell, who has died at the age of 84, was born on May 22 1941 in Glasgow in the midst of the Second World War.

He later claimed he was delivered in an air raid shelter while his father, a joiner, sat outside drinking from a bottle of whisky.

He attended Hillhead High School, then a fee-paying local authority school, from where he won a place to read law at Glasgow University, where his friends included the future Labour politicians John Smith and Donald Dewar.

It was at university that he took up running seriously, representing Britain at the Olympics in the 200 metres and the 4×100 metres relay while studying for a second degree, becoming president of the university union and doing his apprenticeship as a solicitor.

Having also found time to join the university Liberal Club – in part as a reaction against his parents’ socialism – his interest in politics fell away after leaving university and he embarked on a career in law.

It was not until the 1970s that he was drawn back in, becoming chairman of the Scottish Liberal Party at the age of 34, although it was only in 1987 that he finally gained election to Westminster – at the fourth attempt – as MP for North East Fife.

By that time he was married – his wife Elspeth was the daughter of the war hero Major General Roy Urquhart, who commanded the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem, and had a son from a previous marriage.

Looking back in his autobiography, he confessed it was “now a mystery to me” why he chose to pick up politics again.

Initially he only intended to serve two terms at Westminster but once there he became “hooked”.

Following the merger of the Liberals and the Social Democrats, his talents were quickly recognised by new leader Paddy Ashdown, who in 1992 made him the party’s foreign affairs spokesman – a brief he was to hold for 14 years until he became leader himself.

With his forensic eye for detail it was a role in which he excelled, holding ministers’ feet to the fire over the Matrix Churchill arms-to-Iraq scandal when the Tory government was accused of supplying military equipment to Saddam Hussein in breach of their own guidelines.

When Mr Ashdown finally stood down, Mr Campbell was seen as a potential successor but chose not to run, in part because he was seen as being too close to Mr Ashdown’s secret negotiations with Mr Blair to bring their two parties closer together.

It was perhaps ironic then that it was his opposition to the Blair government over the invasion of Iraq that really brought him to the fore.

He and leader Mr Kennedy agonised before committing the Lib Dems to all-out opposition of the war which Mr Blair and US president George W Bush said was necessary to remove Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

“There were some sleepless nights for me and for Charles. All it needed was a company of American marines to discover two tanks of anthrax – our position would have been wholly undermined,” he later recalled.

“So it was a big risk, but we thought it was right and we thought (the war) wasn’t legal.”

Having been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma – a form of cancer – the previous year, Mr Campbell was still recovering from chemotherapy as he watched the TV footage of the tanks rolling in.

“I was a thoroughly informed armchair general and politician,” he remembered.

With the Tories supporting invasion, the Lib Dems became the principal mainstream voice of opposition to the conflict, giving them a rare prominence which Mr Campbell – who was also elected deputy party leader – and Mr Kennedy exploited to the full.

Their position was vindicated as the allied forces failed to find any evidence of Iraqi WMD and the 2005 general election saw them return with 62 seats – the highest tally for the third party since 1929 – while Labour’s majority was slashed.

Behind the scenes, however, there was trouble.

Even as they were opposing the war in Iraq, Mr Campbell had become aware that the charismatic Mr Kennedy had a serious drink problem.

While he remained hugely popular with voters, there was growing concern within the party that it was eroding his ability to do his job.

Matters finally came to a head in January 2006, when Mr Kennedy sought to pre-empt a report by ITN by summoning a press conference to admit he had been receiving treatment for alcoholism.

With Lib Dem MPs in open revolt, two days later he quit.

Sir Menzies (he was knighted in 2004) was immediately seen as one of the front-runners to replace him, but even before the contest was properly under way things started to go wrong.

Standing in for Mr Kennedy at PMQs he sought to press Mr Blair on the shortage of school leaders – prompting hoots of derision from Labour and Tory MPs who made hay mocking the Lib Dems’ own lack of a leader.

It was a deeply uncomfortable experience for a man more accustomed to being treated with respect in the Commons chamber, and while he went on to top the ballot of party members, it set the tone for much of what was to follow.

Even after his election he continued to struggle at PMQs, a forum he did not enjoy, complaining: “It’s theatre, not debate.”

Meanwhile Labour received a boost with the transition from Mr Blair to Gordon Brown, while the youthful Mr Cameron was making waves for the Tories.

With the Lib Dems sliding in the opinion polls, Sir Menzies increasingly found himself facing questions about his age, even though the mid-60s were, in historical terms, hardly unusual for a party leader (He was not helped by the way his cancer treatment had left him looking older).

The final straw came when Mr Brown, having toyed with the idea of a snap election, announced he would be carrying on, meaning Sir Menzies could be 69 by the time the country next went to the polls, bringing the age question into even sharper focus.

With rising discontent among Lib Dem MPs – and party president Simon Hughes publicly warning he needed to “raise his game” – on October 15 2007 he announced he was standing down, the first elected Lib Dem leader not to take his party into a general election.

Nick Clegg, who went on to succeed him, said he had been treated “appallingly” and the subject of “barely disguised ageism”.

Sir Menzies nevertheless carried on as an MP until the 2015 general election, when he was made a life peer as Baron Campbell of Pittenweem.

After his wife died in 2023, after more than 50 years of marriage, he paid tribute to her, describing her as his “constant political companion”.