Containing 90,000 sacred relics from Bowie’s career, the V&A East’s new collection is a shrine to the chameleonic rock star

“I’m finding it embarrassingly hard not to touch this,” admits one of several middle-aged blokes queuing up for a selfie with the sculptural, PVC and velour tuxedo dress that David Bowie wore in one of his most mesmerising TV performances, on Saturday Night Live in 1979. Taking pity on the fan’s yearning for intimate contact with the stiff, shiny bodice, one of the curators at the V&A’s new David Bowie Centre reaches out a purple latex glove and tweaks a corner of the flared waist for him.

A holy hush falls as the small group around the costume crane forward, straining to hear a creak or squeak from the 46-year-old fabric, imaging our own fingers grazing the hem of his garment. But we only hear the sound of another fan inhaling. “It doesn’t smell of anything,” he laments. I wonder what he wanted to catch a whiff of. Vintage plastic? Sweat? Sex? Death? Fame? The latter, chased so hard by the young David Jones, was a place he ultimately found to be as “hollow” as the costume we’re now assessing.

Such are the thrills and disappointments of a pilgrimage to the shrine of the “chameleon” rock star. Containing 90,000 sacred relics from Bowie’s career, the Centre is housed in two rooms at the top of the V&A’s vast, modern East London Storehouse. You climb glass -flanked stairs beneath artificial lighting, past meticulously catalogued shelves of crates and boxes of antique treasures from around the world. The vibe is equal parts Area 51, Raiders of the Lost Arc and IKEA warehouse. You feel the frisson of being behind the scenes.

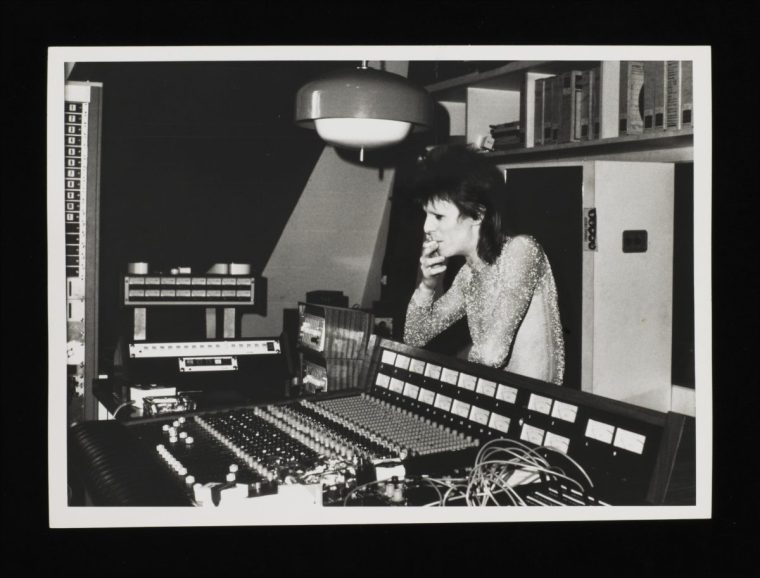

Excitingly, visitors to this weirdly impersonal hangar can conjure a deeply personal experience by summoning up to five specific items from Bowie’s archive to admire. For the press, the V&A curators have laid out the grubby, broken, 12-stringed guitar from his 1972-73 Ziggy Stardust era. There’s a pair of cream silk hot pants with a zip running up the crotch (I hope he either wore tights or waxed well) and the feather topped scarlet pantaloon suit he wore in the 1980 Floor Show with Marianne Faithfull. It’s tiny. Although Bowie was five foot nine, curators tell me they’ve been horrified by how “tiny” his waist was. I’m reminded that when he sent Kate Moss some of his playsuits in 2014, the model was astonished to find they fitted her “like a glove”.

Attracting most curiosity is a double-headed key from the Berlin flat he rented from 1976-79.

“German visitors have been telling us this sort of key is normal over there, but it looks really weird to us doesn’t it,” a curator laughs as I try to picture Bowie trying to use the key during the height of his cocaine addiction. “I don’t think he was meant to have pocketed the key when he left,” mulls another fan. Then again, as he was sharing the flat with Iggy Pop, it seems unlikely they’d have got their deposit back anyway.

Bowie was the Martian Messiah for many of these men in their jeans and well-washed Bowie tour T-shirts. They came of age in the 1970s as the suburban-born David Jones shocked their parents on Top of the Pops with his decadent, alien androgyny. He brought electric blue colour and creativity into a grey decade. For me, born in 1975, Bowie was also the thin white duke who’d gone bonkers on cocaine and – in an infamous interview with Rolling Stone – expressed his admiration for Hitler, gushing: “I believe very strongly in fascism… I dream of buying companies and TV stations, owning and controlling them.”

It’s worth reminding younger readers that Bowie was so uncool by 2002 that he was supporting Moby in the US. But, since his death from liver cancer in 2016, he’s become something of a rock’n’roll saint, the kindly wisdom of his later years – and his prediction of the internet – eclipsing the darker lapses of his youth.

Preparing for future canonisation from his childhood, Bowie hoarded almost every costume, letter, film script, sketch and lyric sheet from his multimedia career. He later employed a curator and left notes for her in a series of yellow post-it notes still stuck to them. It’s a reminder that his magpie genius always lay in the way he collected ideas from sci-fi and surrealism, high and low culture, and alchemised them into perma-shifting sounds and visions of his own. Mick Jagger once joked that every time he hugged Bowie, he always felt his friend’s hand slip into his collar to check the label.

“Yet everything here is from Bowie’s professional life. There is nothing of his personal life in this collection,” stresses a curator. “There are many very personal letters from his fans. They poured out their hearts and stories to him.” Like prayers? “Yes, although some were quite sexual prayers…”

We laugh and I ask her to take a photo of me standing behind the Mark Rivitz-designed PVC suit. In it, he sang “The Man Who Sold the World”, with lyrics winkingly pickpocketed from William Mearns’ 1899 poem Antigonish: “Yesterday, upon the stair, I met a man who wasn’t there…” I look down and see the row of press studs that enabled Bowie to slip out of the costume. Bowie isn’t there at his Centre. But it keeps his sacred mystery intact, while allowing us close enough to smell him.