The family of a learning disabled man who died through neglect after being fed jelly in hospital, have called for better care for people they say are often “just treated as numbers”.

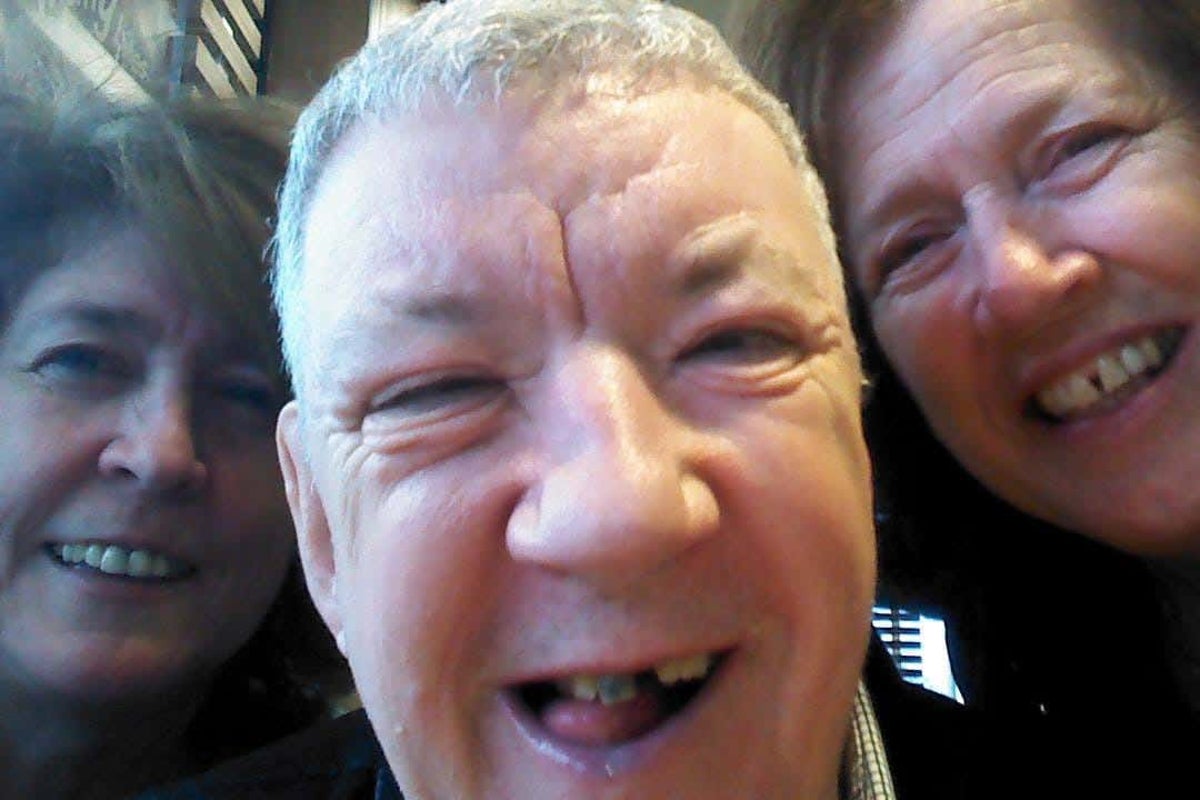

Eddie Cassin, described by his family as “our sunshine”, died aged 66 in June 2023.

His case is expected to be included in the latest statistics in an upcoming delayed report into the deaths of people with a learning disability, and autistic people, in England.

A coroner concluded earlier this year that Mr Cassin’s death was contributed to by neglect, and had he been treated for developing aspiration pneumonia, caused by something such as food getting into a person’s lungs, “he would likely not have died at the time he did”.

The report noted that despite having swallowing problems, known as dysphagia, and therefore having jelly highlighted as a food he should not be given, there was “repeated administration of jelly through his stay” at Milton Keynes University Hospital, where he had not been “properly supervised”.

The hospital’s chief executive wrote to Mr Cassin’s family earlier this month to say they were “profoundly sorry for the failings in the care provided to Eddie which contributed to his death”.

Mr Cassin had been cared for in a home for about a decade before his death, but his family say they encountered a number of problems over the years, including what they saw as overmedication to “keep him quiet”, and an at-times “quite cruel” system lacking in “basic good care and someone to talk to”.

His sisters, Teresa French and Mary Houston, said they felt the need to campaign, in the wake of their brother’s death, for changes in the system to improve care for a “forgotten” group.

Ms French said: “Eddie was lucky, because he had us to speak for him and us to fight for him. There’s so many people that don’t and that’s what saddens me.

“It just saddens me – what about those poor people who have nobody to stand up and speak for them?

“And that just really makes me really sad, that we should have to have people like myself and my sister who go in there and argue the case about someone’s human rights, and somebody who’s a human being, because to me, like Mary said, they’re just treated as numbers.”

The family said they often visited and provided care for him, including taking him for days out, but that things had deteriorated to the point where they felt “it was almost like he became a burden to that care home”.

Ms Houston said: “I just think that in society today, a lot of people are being put into homes and forgotten by the Government.

“Eddie was happy there for quite a few years, but then all of a sudden it was just negativity the whole time, which affected Eddie’s mood and the way he thinks. So, although society is providing care, I wouldn’t say that care is that good.”

On a number of occasions when he became ill and was taken to A&E, the situation became distressing, as Mr Cassin faced sometimes 12-hour waits, Ms French said.

“This is a person with a learning disability who doesn’t understand why he’s there,” she said.

“He doesn’t understand that he’s quite unwell, and he would just get so distressed, he would cry and say, ‘please take me home, I want to go home, I’ll be good’. He thought he was being punished.”

She called for a fast-track system for patients like her brother, while the family also said more “robust” policies need to be in place in hospitals to ensure people with learning disabilities and the care they require is properly understood.

Ms Houston said: “Our society has changed so much, I think, in the last 10 years. I think that they (those with learning disabilities) are just forgotten people by the Government and by various authorities.”

The latest Learning from lives and deaths report (LeDeR), expected to show data for 2023, was due to be published in about November last year but is understood to have been held up over “practical data issues”.

The LeDeR programme was established in 2015 in an effort to review the deaths of people with a learning disability and autistic people in England.

Annual reports are aimed at summarising their lives and deaths with the aim of learning from what happened, improving care, reducing health inequalities and preventing people with a learning disability, and autistic people, from early deaths.

Jon Sparkes OBE, chief executive at learning disability charity Mencap, said: “It’s essential the Government, the NHS and the wider care sector take urgent action on the recommendations set out in the forthcoming LeDeR report.

“People with a learning disability have a right to access good quality and timely care that meets their needs and helps support them to live happy and healthy lives.”

The Department of Health and Social Care has previously said it is “committed to improving care for people with a learning disability, and autistic people” and that the Learning from Lives and Deaths report “will help identify key improvements needed to tackle health disparities and prevent avoidable deaths”.