European powers are racing to reach a diplomatic solution before the end of August

Iran is upping the stakes in its nuclear brinkmanship as European powers race to reach a new agreement on its controversial nuclear programme.

Britain, France and Germany – known as the E3 – face an impending decision as a 31 August deadline approaches on whether to trigger the “snapback” clause under UN Security Council resolution 2231.

This mechanism enables signatories to the 2015 nuclear deal to formally accuse Iran of significant non-compliance, which would automatically reinstate UN sanctions without being vetoed by the council.

The E3 have linked this timing to “termination day” on 18 October, when the resolution’s measures expire. European powers want Tehran to meet conditions including addressing its substantial stockpile of highly enriched uranium, restoring access for UN inspectors and re-engaging in dialogue with Washington.

On Thursday, a report suggested that the E3 were likely to begin the process of reimposing sanctions, but still hoped Iran would provide commitments on the programme in the next 30 days. European diplomats said that in talks this week Iran did not give sufficiently tangible commitments, according to Reuters, but that diplomacy was still possible.

However, following US and Israeli attacks on Iran in June, Tehran has increasingly signalled that the likelihood of political or diplomatic resolution has diminished.

Iran’s strategic reassessment

Since the June war, Tehran’s nuclear calculus appears to be shifting. The war deepened its distrust of Washington and hardened its stance on nuclear diplomacy. Bombed while still engaged in talks, Iran now views deterrence as a more reliable guarantor of security than dialogue with Western powers.

The West has accused Iran of racing to acquire nuclear weapons, which Tehran denies. However, Iran has enriched uranium up to 60 per cent – far above the 3.67 per cent nuclear deal limit and a short step away from 90 per cent weapons-grade.

Following the June conflict, Iran suspended co-operation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its inspectors were pulled out because of safety concerns.

The Iranian regime views the IAEA with suspicion, noted Srboljub Peović, a research assistant at the Institute of European Studies.

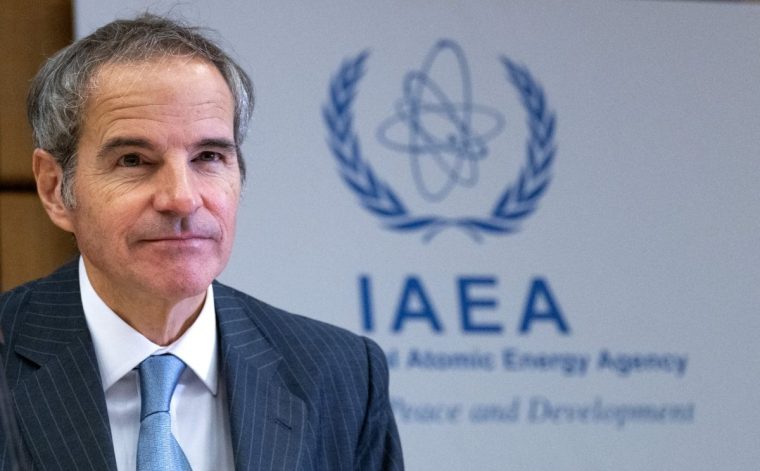

He said: “Iran had already blamed the agency for certain hostile actions in the past, such as leaking a confidential document on Iranian nuclear capabilities to [Israeli intelligence service] Mossad in 2010 that led to assassination of its author. Or the agency’s 2011 report where Iran was accused of weaponising its nuclear programme with no solid evidence. Rafael Grossi, the IAEA chief, was accused by Iran during the 12-day war of leaking documents to Israel and lacking impartiality.”

Top Iranian officials had called for Grossi to be put on trial and and sentenced to death, and the IAEA has confirmed he is receiving round-the-clock protection from an elite Austrian unit following threats, reportedly from Iran.

Britain, France and Germany have condemned the threats against Grossi after they appeared in Iranian media. Grossi did not address Iran’s claims, but said his priority was ensuring UN inspectors could return to Iran’s nuclear sites.

Iranian media reported on Wednesday that IAEA inspectors had returned to Iran for the first time since it suspended co-operation. However, the Iranian foreign minister, Abbas Araghchi, said Iran had still not agreed on how it would resume full work with the IAEA.

As Peović observed, Iran’s struggling economy means it has compelling reasons to pursue an agreement.

Iran has questioned the E3’s legal authority to trigger sanctions and warned it could exit the Non-Proliferation Treaty, suggesting it is concerned about the threatened imposition of more damaging sanctions. “Iran maintains that the JCPOA [nuclear deal] has long been abrogated, and therefore there is no legal basis for the snapback mechanism,” Mehran Kamrava, professor of government at Georgetown University in Qatar, said.

However, Barbara Slavin, a distinguished fellow at the Stimson Centre, doubts this. “With all the other crises afflicting the world right now – Ukraine and the possibility of a US sell-out plus the gaping wound that is Gaza – I’m not sure the Europeans have the stomach for yet another crisis,” she told The i Paper.

Over the weekend, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian held consultations with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, amid preliminary indications that Moscow may be willing to support a six-month extension – potentially contingent on US acquiescence.

Race to the bomb?

Kamrava said it would be unsurprising if Iran pursued a nuclear weapon. “In an era when the organising principle of international relations once again revolves around the notion of might-makes-right, from the perspective of Tehran’s policymakers, having a nuclear weapon appears to be the only viable option in dealing with the United States and Israel,” he told The i Paper.

With the Iran-led “Axis of Resistance” much weaker than it was just a year ago, nuclear capability now figures more centrally in Iran’s assessment of how to project strength.

“Tehran’s takeaway from the conflict is: had we had a bomb, this wouldn’t have happened,” said Dina Esfandiary, Middle East geoeconomics lead at Bloomberg Economics. “The imperative to dash for the bomb will be greater today because of the strikes, and certain parts of the elites are calling for exactly that.”

However, she said that Iran was wary that a race for the bomb could invite US-Israeli military retaliation.

“The technocrats running Iran today don’t want to do that and, in any case, believe that if they did make a dash for it, it would likely be detected. Instead, Iran is likely to drive its programme further underground and make progress on it as quietly as possible,” she added.

Rouzbeh Parsi, an adjunct senior lecturer at Lund University in Sweden said that Iran’s ability to achieve deterrence probably required a nuclear weapon. He said the central questions now were how much of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure remained intact, how quickly it could be rebuilt, and to what extent such efforts might evade detection. The Iranians “need to tread carefully, especially as now Israel has broken the taboo of a direct attack against Iran and the Americans have been in effect assisting them”, he said.

Although Trump claimed the US had “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear programme, initial Western intelligence assessed it was likely that Iran’s stockpile of 408kg of 60 per cent enriched uranium remained largely intact. Veteran war correspondent Elijah Magnier noted in an interview with The i Paper that this “revelation struck at the heart of Trump’s victory claim, exposing the gap between political messaging and strategic reality”.

Future escalation

As legal and diplomatic frameworks erode, the risk of renewed military confrontation grows. Iranian officials see the current pause in hostilities amid this current ceasefire not as lasting peace, but as a window to rearm and absorb lessons from the June war.

While another US strike may not be imminent, Trump will keep the option alive. “The risk would escalate sharply if Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, facing intense domestic pressure, were to seek another war as a political escape route – a tactic he has relied upon repeatedly over the past two years. Should Israel choose to strike Iran, Washington under Trump is almost certain to follow,” warned Magnier.

As Iran recalibrates its nuclear strategy in a conflict-prone region, whether it chooses opacity and deterrence or re-engages diplomatically will shape not just its future, but the Middle East’s broader security architecture. In a world increasingly defined by machtpolitik, Tehran’s next move could reshape the nuclear status quo.