From the age of six, Jacqueline Wilson knew she wanted to write books for and about children. She wanted to portray them as they are “and not the way parents want to think of them. I think parents often forget what they were like when they were young”.

Wilson, however, can recall every detail of her childhood in Kingston, London, and how she felt and saw the world. Her parents were difficult people “who cordially hated each other”. Her mother “didn’t have the ability to see me as a separate person. She’d wanted a Shirley Temple-type all-singing, all-dancing girl with lots of curly hair. And I had straight hair, I was shy and I wore glasses. She made it plain that I was a bit of a failure”.

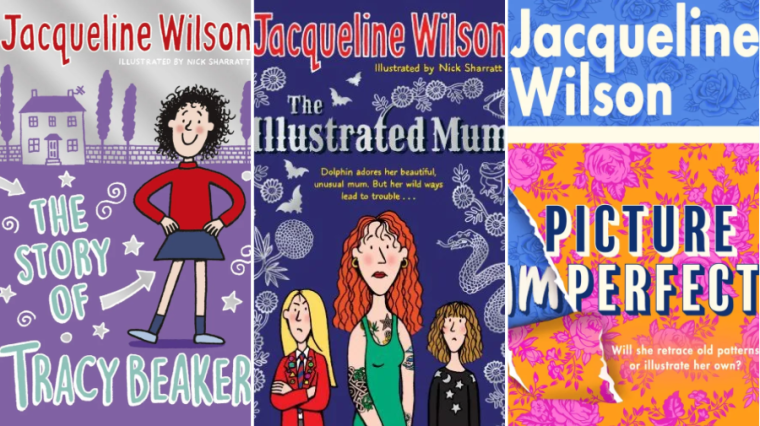

Yet Wilson would grow up to be a prolific and wildly successful children’s author, becoming the fourth Children’s Laureate in 2005. Three years later she was awarded a damehood. The author of over 100 books, Wilson is responsible for creating indelible and cherished characters including Tracy Beaker, a young tearaway growing up in care, and Hetty Feather, a red-headed Victorian foundling – both of whose exploits were later adapted for TV.

Did Wilson’s mother ever show any pride in her daughter’s achievements? “Oh no,” she replies. “She never read a single book of mine, not even the one dedicated to her.” She recalls visiting her mother in hospital when she was near the end of her life, by which time she had dementia. “And I did something that irritated her at visiting time, and she yelled at me, ‘I never liked you. Never!’ A nurse came along and took me by the arm and said, ‘Please don’t take it to heart as she doesn’t mean it.’ And because I’m a people-pleaser I thanked her. But, of course, I knew she really did mean it. But what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

I meet Wilson – who is 79 – at her publishers’ offices in London. She is instantly recognisable with her cropped silver hair, twinkly smile and distinctive, chunky silver rings, each of them decorated with gemstones including rose quartz, topaz and moonstone. One of the reasons she loves jewellery is because her mother forbade her to wear any when she was young.

She and her partner Trish, a bookseller, live on the outskirts of a small East Sussex village where they have two dogs, a cat, four hens and a view of the surrounding countryside. “I didn’t think I’d ever be the person that would be all” – she adopts a soppy voice – ‘Oh, what a sweet little doggy’,” laughs Wilson. “But here we are.”

We are here to talk about Picture Imperfect, Wilson’s new sequel to her much-loved 1999 children’s novel The Illustrated Mum, which was turned into a TV movie starring Michelle Collins. That book was about 10-year-old Dolphin, who lived with her older sister, Star, and their hard-drinking, heavily tattooed mum Marigold, who suffered from bipolar disorder.

Written for adults, Picture Imperfect picks up the story 23 years later, with Dolphin now a 33-year-old tattoo artist who is still intermittently looking after Marigold. Wilson imagines a lot of readers will be around the same age as Dolphin, having read the first book as children. “I hope they might be interested in seeing someone who hasn’t had this amazing happy ending,” Wilson notes. “These are not people that have always had happy lives.”

This isn’t the first time Wilson has revisited past characters in a book for adults. Last year she published Think Again, a sequel to Girls, her book series about teens navigating friendship, puberty and crushes. In Think Again, those girls had reached their forties and were reassessing their lives. “[Going back to old characters] is my unique selling point,” Wilson smiles. “Not a lot of authors have had such a long career as I have. I started early and I’ve gone on way past retirement age, and I’m determined to carry on as long as I’ve got the creative juices.”

Of all her books, she notes, The Illustrated Mum “had the strongest response. I had lots of letters [from readers saying] they really took her to their hearts. There are a lot of kids who, while not necessarily having a parent with bipolar disorder, have an unreliable parent, and so the book resonated with them.”

For Picture Imperfect, Wilson didn’t have a clear plan for Dolphin until she started writing. “It sounds very fey and silly, but I didn’t know what happened [to her]. I’m not a writer that plots it all out and has little notes all around the study. I started writing and almost immediately, I seemed to get into her head. It was as if I’d met her all over again.”

There is another new development in Think Again and Picture Imperfect, which is that both books contain sex. Noting my surprise, Wilson laughs and says: “I think if I’d never written any books before, people would almost expect me to have sex scenes. But because I’ve been known as some kind of Mary Poppins figure, people think, ‘Oh, my goodness, what’s all this?’”

The whole experience of writing for adults has been “incredibly freeing”, though she admits she did have a moment, when doing a promotional event for Think Again in her village, “when I found my throat drying rather, and my heart thumping. None of the sex scenes are [based on] anything that I’ve actively done, but you could see people thinking, ‘Ooh, has she done that?’ And a lot of people do seem to think that when you’re writing fiction, you’re inevitably writing autobiography. But I would have led a very strange life if that were the case.”

An only child, Wilson loved reading from an early age. She recalls reading Noel Streatfeild, author of Ballet Shoes, and admiring the children in her books “who were sometimes grumpy and difficult”. At 13, she recalls asking for one of the books in Catherine Cookson’s Mary Ann series, which, far removed from the romances that made the author famous, featured a young girl living in poverty in a Tyneside tenement with an alcoholic father. “It meant a lot to me because Mary Ann was a real child, and I understood her.”

If there is a common theme in Wilson’s books, it’s her compassion for women and girls and the challenges they face. Over the years she has tackled themes of divorce, friendship, parental neglect and the care system, though she notes that, for her, the character always comes first. “Basically, I want to write a book that children will want to read. But [telling these stories] is also my way of encouraging children to have empathy. That if there’s a weird girl in your class that has a really odd mum, it’s good to try to be kind. I’ve always sided with the child who is a bit of an odd one out.”

Success on a grand scale came late to Wilson, who spent her twenties and thirties supplementing her income by writing for teen and women’s magazines. “I would do the articles in the mornings and return to the books in the afternoons. I wrote thousands of words every day. How I kept up that schedule I will never know.”

Her breakthrough book was 1991’s The Story of Tracy Beaker, which got a further boost when it was adapted into a series on CBBC. Though Wilson had no direct experience of living in care, the cruelty and tumultuousness she experienced as a child fed directly into her books. A decade later, hers were the most borrowed titles from British libraries.

Wilson can still recall the feeling of “absolute joy” when her books started to make money. “Although when it’s happening,” she notes, “you don’t quite grab hold of it.” Now, at a time in her life when she imagined work might be winding down, “to have the chance to reinvent myself [as a novelist for adults] feels absolutely wonderful, even though I still plan to write one children’s book a year. I’m greedy, you see. Not for money but for expressing myself. Because what else am I going to do?”

‘Picture Imperfect’ is published by Bantam on 28 August