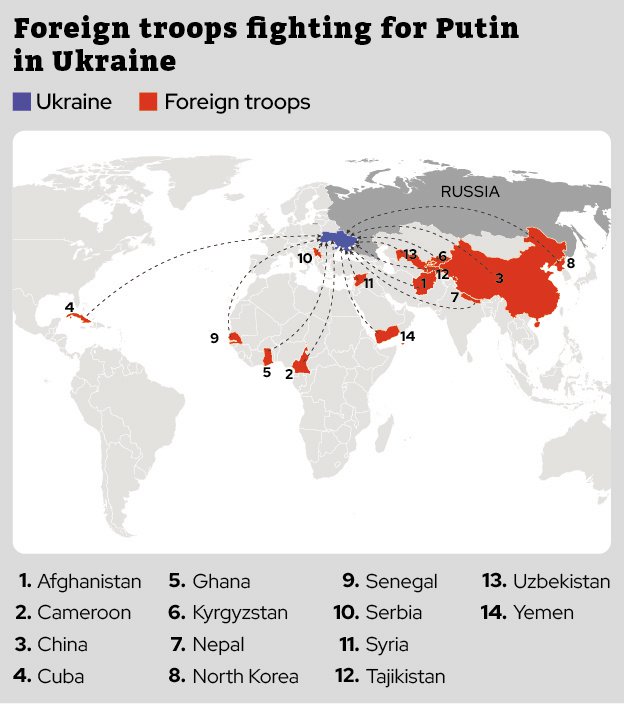

From Africa to Central Asia, Russia’s president is using coercion and military agreements to bolster his forces with a growing group of foreign fighters

As the war in Ukraine stretches into its fourth year, Vladimir Putin‘s army of invaders remains bolstered by his growing reliance on foreign forces. From remote villages in Africa to military compounds in North Korea, a patchwork of non-Russian support — both official and unofficial — has strengthened Moscow’s campaign.

Though the true scale of Putin’s foreign legion remains unclear, publicly available evidence suggests the total number of foreign recruits runs into the tens of thousands. Helping the Russian leader to avoid further unpopular mobilisations among his own citizens, the Kremlin is outsourcing parts of its war to some of the world’s most vulnerable communities.

The UK’s defence attache to Moscow until 2022, John Foreman, said the Russian army began “morphing into a militia” at the start of the war, following heavy casualties to the Kremlin’s invading forces.

“Russia has cast its net wide for replacements; volunteers, foreign mercenaries, criminals, North Koreans and ad hoc mobilisations. These men from different pools of meat have kept Russia fighting,” Foreman said. “Of course they are treated as cannon fodder, are low grade, endure terrible conditions, and suffer hideous racism.”

As world leaders push to get Russian and Ukraine around a table in the hope of striking a peaceful end to the war, The i Paper examines the foreign troops motivated by ideology, money, or coercion into fighting Russia’s invasion.

North Korea

Last November, North Korea became the first country to formally deploy troops to aid Russia in Ukraine. Ukrainian forces reported troops from the country forming part of a Russian offensive in the Kursk region – a southern Russian region which was partially captured by Ukrainian forces earlier this year.

Since then, over 11,000 North Korean soldiers, including special operations personnel, sappers to clear mines and military construction workers have been reported on the battlefield by Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence (HUR).

South Korea estimate North Korean casualties to have reached over 600, including six officers who were reportedly killed in a Ukrainian missile strike.

Last month a Russian military aircraft, operated by Russia’s air force, landed in Pyongyang after flying over Siberia and returned to Moscow after a 2.5-hour stop. Analysts at independent conflict analysis firm Acled Data suggest the landing could have involved transporting senior military personnel or the remains of killed North Korean soldiers back to the country.

Putin said: “The Russian people will never forget the heroism of the Korean special forces. We will always honour the Korean heroes who gave their lives for Russia and for our shared freedom, alongside their brothers-in-arms from the Russian Federation.”

However, the coalition has been far from successful. According to Ukrainian and American officials, North Korean troops operate “rather autonomously” and were often an “unwanted distraction” for Russian troops in Kursk.

North Korean soldiers have allegedly been involved in fatal instances of friendly fire against Russian forces.

A Ukrainian military intelligence officer said North Korean soldiers “usually killed themselves” when faced with capture. He added: “The North Koreans are fairly useless in warfare but there presence in Ukraine represents the growing relationship between Russia and its allies.”

China

While the Chinese government has not officially contributed combat troops to the war in Ukraine, over a hundred Chinese nationals have joined Russian forces as mercenaries.

According to US and Western intelligence sources cited by Reuters, Chinese mercenaries – believed to be veterans or former security personnel – are not formally linked to Beijing but are present on the battlefield in order to study the conflict and send information back to China.

In April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said his forces had captured two Chinese nationals fighting for the Russian army in eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk region.

In a statement on X, formally Twitter, Zelensky said intelligence suggested the number of Chinese soldiers in Russia’s army was “much higher than two” and the soldiers were captured during a gunfight with six Chinese soldiers.

Dr Sari Arho Havrén, a associate fellow at the Rusi think-tank and China analyst, described the developments as “deeply disturbing” and present further evidence of China’s growing alignment with Russia.

Dr Havrén said Chinese troops are observing the “tactics and outcomes” of US and Nato capabilities in the battlefield to help plan for potential future confrontations.

She told The i Paper: “I would say it is close to certain that at least some of the Chinese mercenaries fighting in Russian army in Ukraine are designated for the purpose of gathering information and intelligence.”

Africa

Hundreds of African men are reportedly fighting for Russia in Ukraine. As the Russian military’s “meatgrinder” operation has cost the country thousands of casualties, Russian authorities have looked to recruit from areas where they hold significant influence.

The former Wagner Group in Africa – now named Africa Corps – has built a stronghold in central African nations, where Moscow has sought to fill the void left by retreating Western influence. The influence of Wagner’s presence has allowed the Kremlin to tap a well of potential fighters for use in Ukraine.

Men hailing from Senegal, Ghana and Cameroon have joined units referred to as “Black Wagner”. These fighters, deployed across eastern Ukraine, are often under-equipped and poorly trained, serving as expendable assets on the front lines.

In 2022, it was reported that at least 42 African mercenaries had been killed in Ukraine. That figure is believed to have increased significantly, while others have been taken prisoner and are stuck on the front line.

Milosz Bartosiewicz, a research fellow at the Centre for Eastern Studies (CES), said Russia had successfully recruited fighters from at least 20 different African countries using methods which are “basically human trafficking”.

He told The i Paper: “They lure people in order to work in Russia and then they force them to sign a military contract.

“They promised them that their families, in case they die, will be provided with some financial support, but it’s not clear if that ever comes.”

In April, Ukrainian forces released a video of a Senegalese man they had captured fighting for Ukraine. They claimed his name was Malik Diop and that he signed a contract with the Russian Armed Forces, and was promised a position as a cook.

According to a France 24 investigation, many African recruits were duped into fighting in Ukraine with promises of lucrative wages, employment opportunities, or Russian citizenship.

For some, the opportunity appeared genuine. Others have been reportedly deceived or coerced into joining the conflict involving exploitative contracts or threats.

Men are recruited by agents working for the Russian state and presented with contracts written in Russian – a language they do not speak – to become conscripted into the war, according to France 24’s report.

Central Asia

Russia has also turned to migrant workers from Central Asia to replenish its forces in Ukraine. Fighters from Central Asian states now make one of the largest group of Russia’s foreign forces with more than 3,000 troops.

Over 350 fighters from Central Asia have died in the conflict, according to figures released by Ukraine’s Defence Ministry.

The bulk of these recruits come from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, countries where millions of migrants travel to Russia each year for employment. It’s estimated that there are over 10 million Central Asian migrants in Russia – many of them undocumented and unprotected by labour laws.

This, according to a recent report by the Atlantic Council, leaves them open for exploitation and recruitment to the frontline.

Migrants, who previously worked in Russia as cleaners, street sweepers, or construction workers are lured into the conflict under promises of fast-track Russian citizenship, according to the report.

Bartosiewicz said labour migrants from Central Asia who came to Russia in order to work were brought over through organised campaigns set up to “enforce” them into signing military contracts.

He said: “Those people are being chased, being captured during police raids on hostels, on the mosques or on restaurants, on markets, marketplaces, factories where they work.”

Syria and Yemen

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), Moscow has recruited around 2,000 Syrians, many of them drawing from the country’s special forces.

The recruitment campaign stems from a longstanding relationship between Russia and its once staunchest ally in the Middle East, the former Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

Fighters enlisted from the country mainly came from the Syrian government’s troops, who fought alongside Russian forces to secure Assad’s leadership in 2015.

Syrian recruits reportedly undergo military training before being deployed to the front lines in Ukraine. They were first reported to be engaging in combat alongside Russian forces in September 2022.

Casualty reports soon followed. In November 2022, SOHR confirmed that 10 Syrian mercenaries had been killed in Ukraine, including a young man who reportedly died while fighting alongside Russian forces on the frontline in the Eastern region of Luhansk.

Experts say the choice to fight in Ukraine reflects desperation rather than ideology. With limited prospects in their home country, Russia’s promises of better pay and improved living conditions have proven persuasive.

Dr Joe Devanny of the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, said: “Using foreign fighters is a way for Russia to increase numbers whilst mitigating the domestic costs of the war.

“Foreign fighters have been recruited differently, including by coercion and false promises. So, whilst ideology might be a motivation in some cases, many foreign fighters are likely there due to economic circumstances or not of their free will.”

Similar recruitment schemes have reportedly operated in Yemen, where intermediaries are accused of using deceit to secure recruits before transporting them to Russia.

A Houthi-linked company has recruited hundreds of Yemeni mercenaries for Russian forces, according to the Financial Times. Travelling under the promise of high salaries and Russian citizenship, they are forcibly sent to the front lines in Ukraine.

Other nations

The CES estimates that thousands of citizens have been deployed from countries in the Global South, including Cuba, Nepal, Malaysia and Afghanistan.

Nepal has been one of the most affected, with estimates suggesting that as many as 15,000 Nepalese men may have joined Russian ranks, often lured by promises of money and citizenship.

The Nepalese government has banned its citizens from seeking employment in Russia or Ukraine and formally requested the return of both survivors and the bodies of those killed.

Several hundred Cubans are also believed to have been enlisted to fight by Russian recruitment networks in the country. The Cuban foreign ministry condemned the trafficking of mercenaries, but the country’s ambassador to Moscow said there was no objection to Cubans serving in Russia “as long as it is legal”.

According to CES around 100 Serbian nationals are fighting alongside Russian forces in Ukraine, with the majority reportedly driven by ideology rather than economic benefit.

Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić warned Serbian mercenaries that they will face legal consequences if they join Russia’s fight, despite the country’s pro-Russian sentiments on geopolitical issues.

Rogue fighters

The Kremlin has also managed to attract a mix of volunteers from Western countries, including the UK.

Aiden Minnis, a 38-year-old Brit from Chippenham has publicly boasted about “killing Ukrainians” while fighting for Russia. Minnis described himself as “happy to be on Russia’s side” and dismissed accusations of treason from critics. He is believed to be part of a small cohort of Brits fighting for Moscow in the war.

Similar volunteers have joined the cause from the UK’s closest ally. The most notable coming in the form of Michael Gloss, the son of Juliane Gloss, the CIA’s Deputy Director of Digital Innovation, who was killed fighting alongside Russian forces in April last year.

Beyond lone fighters, small ideological contingents have also joined Russia’s war effort. A handful of Spanish socialists travelled to eastern Ukraine to fight for pro-Russian separatists claiming to repay Russia for Soviet support of Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.

On the far-Right, several extremist networks have mobilised European groups to build forces for Russia. One of the largest among them is Continental Unity, a French organisation accused of funneling extremists from across Europe into Donbas. Other similar groups have spawned in Hungary and Bulgaria.

As the Atlantic Council’s Katherine Spence wrote : “Russia’s use of foreign troops is a dangerous trend that promises to prolong the war and has the potential to fuel international instability.”