“It was kind of bittersweet, to be honest, listening back to old outtakes,” says The Cranberries drummer Fergal Lawler. He’s talking about delving into the band’s archives to find material for the new extensive reissue of 1994 album, No Need to Argue. “Dolores is speaking in between takes. And it was hard. There’s lots of fond memories from that time. But I maybe didn’t expect that to be as difficult as it was.”

The Cranberries story – the Limerick underdogs who sold more than 40 million albums thanks to timeless international hits like “Linger” and “Zombie” – is permanently underlined by the tragic death of singer Dolores O’Riordan, who on 15 January 2018 accidentally drowned in the bath tub of a London hotel due to alcohol intoxication.

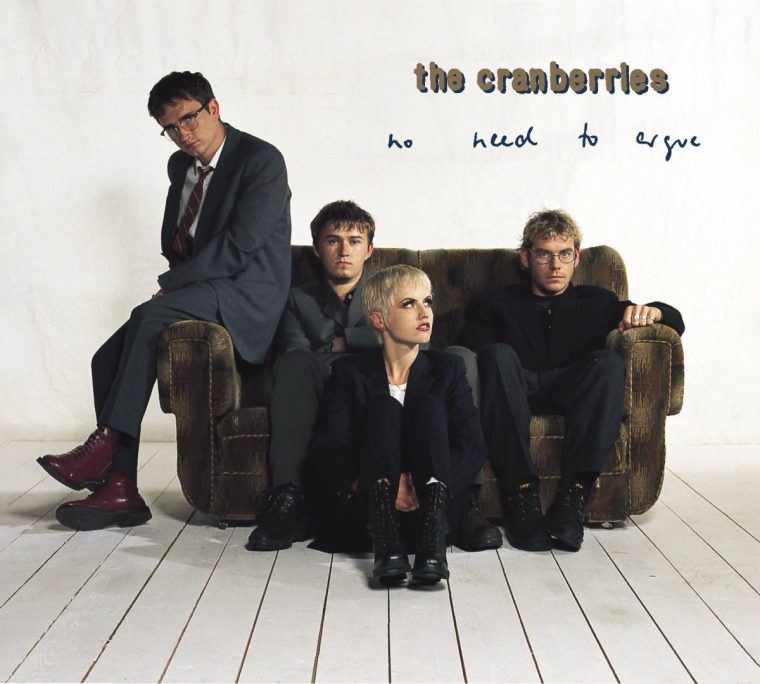

But O’Riordan’s rare star quality, unique, soprano-meets-Irish-lilted yodel of a voice, heart-on-sleeve lyricism and fearless personality endures. The extended 40-track No Need to Argue, which originally sold 17 million copies, allows fans a deeper dive into the creative process, with unheard demos and live cuts, as well as remixes from Chvrches’ Iain Cook. “It’s a lovely legacy to have these albums,” guitarist Noel Hogan says. “I do look at them as a celebration of someone’s life.”

By 1994, The Cranberries were already huge. After initially flopping, 1993 debut album Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? shifted seven million copies after hits “Linger” and “Dreams” got heavy rotation on US college radio and MTV, with success in America – where Irish ties are strong – boomeranging back to the UK.

O’Riordan had written “Linger” a week after she first auditioned for the band (whose lineup included Lawler, Hogan and the latter’s brother Mike Hogan on bass) as a shy kid from County Limerick’s Ballybricken. “Our very first gigs, Dolores would stand sideways to sing as she was really nervous,” Lawler says. But by the time it came to record No Need To Argue, she had grown into a star. “She was a lot more confident,” Hogan says. “Nothing seemed to faze her. It turned out she was literally born to do this.”

Written and demoed on the road in America and produced by Stephen Street, No Need to Argue was the opposite of a difficult second album. With the UK fixated on Britpop and deeming The Cranberries uncool – “you felt like you were a bit on the outside,” Hogan says – the band simply got on with writing what Hogan calls “simple songs” that didn’t chase trends and have stood the test of time.

O’Riordan, who by then had met her future husband, Canadian music manager Don Burton, was writing more personally introspective and emotive songs: beautiful lovestruck ballad “Dreaming My Dreams” sat alongside the gorgeous, heart-tugging “Ode to My Family”, a lament about missing home on tour. Written in hospital after a skiing accident, the closing title track, about moving on from her previous relationship, saw O’Riordan play the organ, an instrument she performed in church as a child.

But one song, an outlier in the band’s canon, took them stratospheric. “Dolores came in one day and said, ‘I have an idea for a song, but it needs to be really angry’,” Lawler says. “’Have you got any distortion pedals?’” That song became “Zombie”, a worldwide smash hit that was written in response to the IRA’s bombing of Warrington in 1993, which killed two children, Jonathan Ball and Tim Parry.

The label, wary of the controversial lyrics, had to be convinced it was a single, yet it grew into something bigger than even the band themselves. The Ireland national rugby team recently adopted it as their anthem. “That’s bizarre,” Hogan says. “I guess I’ve mixed feelings about ‘Zombie’. We have a lot to be grateful for. But it’s overshadowed everything else.”

It wasn’t the only contentious topic O’Riordan covered on the album. “The Icicle Melts” was a response to the murder of toddler James Bulger in Liverpool in 1993. Did the band ever discuss lyrics with O’Riordan? “Never,” Lawler says. “That was her thing. She never told me what to play. I never told her what to say. If something affected her, she’d write about it. She never thought about the consequences. It was like, this is my emotion. I want to express it.”

There is consensus that the band’s third album, 1996’s For the Faithful Departed, was when things started to go wrong. “Everything was good up until then,” Hogan says. “Then the chickens came home to roost.” They both agree the album suffered from being rushed amid label pressure to get another money-making record out, while the sheer level of fame – the band were still in their early 20s – was taking a toll.

“I started having panic attacks through that third album, which is something I never had before or since,” Hogan says. “But the pressure was on big time for Dolores far more than the rest of us. She couldn’t go anywhere, do anything. Even in Dublin she would be hounded everywhere she went.”

By the late 90s, Riordan was struggling with depression and anorexia. “We did an MTV awards thing,” Hogan says, “and you see on YouTube how emaciated Dolores is in it. She’s extremely thin. And I didn’t even notice at the time. You’re not noticing what’s happening to the others. I’m over here with my panic attacks, Dolores is over there with her demons. I’m sure the two boys had their own things going on as well. You’re almost on autopilot.”

O’Riordan eventually escaped to Canada with Burton and their three young children to a remote town outside of Toronto. But even that didn’t halt sexist coverage from the press. “In some ways it was like the dark ages,” Hogan says. “I know it used to piss her off, and rightly so. She used to get that thing, ‘What’s it like being the only girl in a boy band?’ And she’d say, ‘You can ask them what it’s like to be in my band’.”

Lawler tells a story that O’Riordan once turned up to a photoshoot and was expected to strip naked and jump out from inside a cardboard box. “And she said, ‘What the fuck is that about? I’m not doing that.’ That’s when bad press then comes in: ‘Oh, she’s really difficult, she’s really awkward’. And it’s like, no, she actually just stands up for what she believes in.”

“I think she did the best she could with it,” Hogan says. “But she was happiest away from it, just being normal Dolores, not the superstar.”

O’Riordan revealed her demons publicly in 2013, when she told the Irish Independent that she had been sexually abused between the ages of eight and 12 by a family friend, and revealed she had attempted suicide. The band had no idea until just before she went public. “She never gave any indication of any of that ever – you could have knocked me over,” Hogan says. “Not even in the songs, which were her release valve. But then that answers a lot of those questions of why and how we got to the place we ended up.”

The public reveal coincided with a troubling period for O’Riordan, who, post-split from Burton, was arrested in 2014 after a manic episode mid-flight from New York, during which she assaulted cabin crew. But by the start of 2018, O’Riordan was happy and settled as the band worked on new music. “She was in good form,” Lawler says. “She was looking forward to getting new music out.”

It made the shock of her death all the more difficult to comprehend. “That was one of the harder things to deal with, because I felt that the old Dolores had come back,” Hogan says. “There was a few years in there where even her and I fell out for a while. A lot of it was to do with alcohol and the behaviour around that. But we patched that up. And she’d met a guy who was really good for her, really nice, and he dealt with all her demons.”

The band were in talks to do a tour of China. “Then the day before she passed away she texted me about songs that we’ve been working on,” Hogan says. “It [her death] was the biggest shock of my life.”

“There’s still some days I wake up and expect to see an email popping in from her, or get a call,” Lawler says. “I don’t think it’s something I’ll ever actually get over.”

Having got the blessing of O’Riordan’s family, the band set about completing their final album In the End in the immediate weeks after her death. “Oh Christ, it was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done in my life,” Lawler says. “It was crazy, but I’m glad we did it. I’m really proud of that album.”

Stephen Street had encouraged the band to do it. “He said, ‘Your emotions are going to be really raw. You’re going to do your best, and if you wait then you might never do it. And she wouldn’t want that. She wanted to be heard.’ And he was right.” But it was a tough process. “Dolores used to come in the evening and do her vocals, and when we finished up at the end of the day, we were looking down the hall almost expecting her to walk in.”

“I think the boys would agree that the hardest day was the last day,” Hogan says. “Because we knew the three of us – this is the last time we’d all be in the studio together as The Cranberries.”

It proved a critically acclaimed full stop for the band, worthy of O’Riordan’s memory. How do they view her legacy? “I mean, she was born with that voice, right?” Hogan says. “And she genuinely didn’t care what people thought. That filter wasn’t there. We’d all love to be that carefree.”

“All the other stuff that happened through all the years, it fades into the background,” he adds. “It’s the songs people will remember Dolores for.”

No Need to Argue 30th Anniversary edition is out now