President Donald Trump is likely to meet a chorus of ‘I told you so’ upon his return to slow-news Washington in August. His protestation that the meeting with Vladimir Putin was ‘ten out of ten’ and highly productive will sound hollow to those who had, along with President Trump himself, hoped for an instant cease-fire or even an outline settlement.

In truth, the picture is more mixed, depending on the issue one chooses to focus on when considering the negotiating process with a little more distance. The US, Ukraine and Western Europe, seem to have lost one preliminary battle in terms of process. But then, they may not have been in a position to win on that point.

For months, the US President has demanded a cease-fire. It might be a truce of 30 days, but would likely extend as substantive negotiations about the actual political settlement progress.

Given its present dominance on the ground, Moscow has rejected this sequencing, demanding a settlement, or an outline for a settlement, first, before a ceasefire can take hold. This is logical from the perspective of the Kremlin.

If a potential settlement does not meet Putin’s broad demands for Ukrainian neutralisation and parts of its territory, then the alternative is what it has been since the beginning of the ‘Special Military Operation’ on 24 February 2022. That quite simply consists of the use of military force as a means to secure the desired political objectives in the mode of 19th century imperialism.

While the West has adopted ever tighter sanctions against Russia and has been quite effective in boosting Ukraine’s ability to withstand the military onslaught through the delivery of military aid, it has not had the ability to remove the military option for Moscow as a means of realising its goals.

The reason is twofold. First, it is clear that the West, or Nato, cannot become directly engaged militarily, countering military aggression with collective defence of Ukraine at the risk of launching World War III. Hence, there is no prospect to remove the military option for Putin through the threat or reality of a military response.

Second, and critically, the global system of collective security has collapsed. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, virtually all states contributed to the nearly absolute economic and diplomatic isolation of Iraq. Later, the UN Security Council even mandated the use of force.

Sanctions can only work if all participate. But now, it is only the West that has acted against open aggression and in defence of the supposedly universal principle that the international use of force must be resisted and reversed. The states of the Global South, including the most powerful members of the BRICS Group, assert that the invasion of Ukraine is a European, or Western problem that does not involve them.

This means that sanctions are no longer the uniquely powerful and decisive tool they used to be. When balanced against the perceived interest of a revisionist power like Russia under Putin, the costs imposed by sanctions still do not outweigh the supposed gains of completing the aggressive war, at least for the next few years.

The quite recent attempt to opt for third-party sanctions against states that undermine the Western sanctions against Russia represents an attempt to overcome this problem. If the Global South does not want to participate in sanctions, we will force them to do so.

The trouble with this option is that it does not only disrupt relations between third states and Moscow. It also disrupts relations between the West and the targets of third party sanctions.

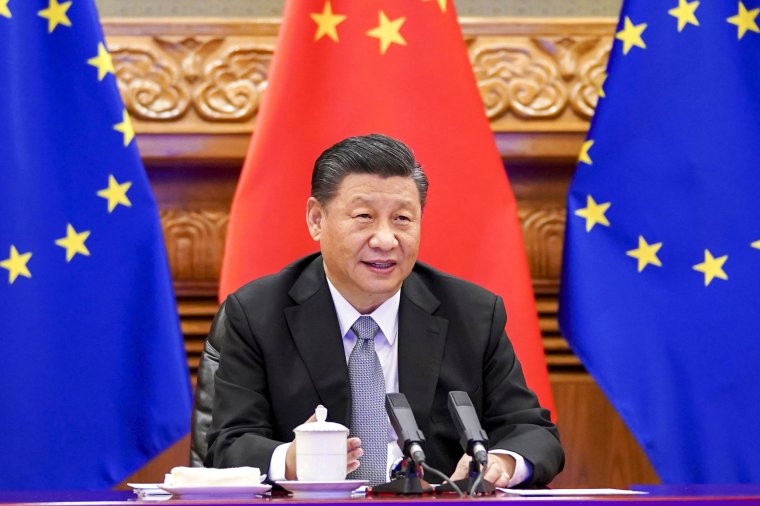

In finally imposing such measures against India when Russia kept resisting the call for a cease-fire, President Trump has admitted that he cannot at this point afford to aim for the more decisive target, China. Having just extended the period of negotiations for a critical trade deal with Beijing, he cannot at the same time sanction it over its support for Russia.

There is some room for increasing economic pressure on Moscow by seizing assets abroad or adopting more third-party sanctions. But this would not immediately impel Vladimir Putin to experience a change of heart over Ukraine and cease firing, although even greater economic pressure may have an effect in the longer term.

If there is no military option, and if sanctions in themselves will not end the conflict, then the only available avenue is diplomacy. But diplomacy can only yield a settlement if both sides in the conflict are ready to settle.

Trump has forced Volodomyr Zelensky – against his better judgement – to accept the prospect of both a ceasefire and a settlement, but he lacks similar power over Putin. Hence, he has been unable to extract a ceasefire as a price for substantive negotiations from the Kremlin. This does mean that Putin has chalked up a procedural victory – his demand for an agreement of at least the base-points for a settlement before a truce will be granted still prevails, even after Anchorage.

In addition to the failure to silence the sound of arms, the Alaskan adventure will now also likely be criticised as having failed to advance a substantive settlement. This criticism from the Europeans is rather hypocritical. After all, they have insisted all along with President Zelensky that no substantive agreement can be offered by Trump without the involvement and agreement by Ukraine. It seems unfair to criticise the US for having failed to do just that.

Rather, the White House claims that the summit has clarified areas where agreement is possible, and ‘one or two’ critical points of disagreement that remain. In his Fox interview upon the conclusion of the summit, Trump noted that it was now for Zelensky to decide how much he is willing to give in order to end the slaughter.

It is something of an indictment that it has taken a top-table effort to identify the critical areas of disagreement that remain. This would of course have been the essential task for Steve Witkoff and his five missions to Moscow thus far. It is rumoured that Witkoff somewhat misrepresented the extent of flexibility Putin was willing to grant, leading to the instant decision to convene the summit the minute he left the Kremlin last week.

Despite the outcry over the exclusion of Zelensky from Alaska, it was right to keep him away from what turned out to be a venture to seek to understand the Russian position better and perhaps to test Putin’s resolve. An angry shouting match between two or three Presidents might have otherwise resulted, throwing the negotiating process back. Instead, Trump has now offered Zelensky, the UK and the EU states the opportunity to help find acceptable ways of overcoming the points of deadlock.

It is not yet known what the areas of major disagreement with Moscow revealed at the summit were. Presumably, this includes the issue of the territorial delimitation of the ceasefire line that will likely become frozen as a de facto border over time. The issue of land swaps was somewhat loosely raised by President Trump in the run-up to Alaska.

In fact, Zelensky has already accepted that territorial change will need to be reflected in a settlement, provided this does not imply a formal legal recognition of that outcome. Moscow, on the other hand, may still demand more territory than it has captured thus far. Some reports suggest that Putin offered to freeze the front lines in two provinces, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – if Ukraine surrendered the entirety of the Donbas. If the Kremlin is willing to ‘swap’ territory, then the price would likely be de jure recognition of its annexations obtained through force. This is difficult or impossible to deliver for Ukraine and the West. However, it is not impossible to come up with ways to circumvent this problem, and Anchorage may well focus creative minds on this issue.

The second sticking point that likely remains is that of security guarantees for Ukraine. Nato membership is out, as is the opposing vision of Putin for a fully neutral and militarily incapacitated Ukraine. Again, the summit may well have helped focus the US mediators on what can be offered to bridge the gap between the sides.

When seen from that perspective, the expedition to Alaska was a risky move for Trump in terms of his reputation. There was no ceasefire and it was unlikely that there would be one. Still, it was a necessary step in terms of the overall negotiating process.

Putin ended the summit by maintaining that Moscow’s fundamental and supposedly legitimate interests must be respected in a settlement. His reference to addressing the root causes of the conflict is code for his long list of demands that cannot be accepted. However, there now exists a top-level format where the sides can more seriously explore whether a settlement, which must come eventually, can be found even now and even in relation to the remaining critical points of disagreement, before even more lives are lost.

Marc Weller is Professor in the Department of Politics and International Studies in the University of Cambridge and a former Senior United Nations Mediation Expert.