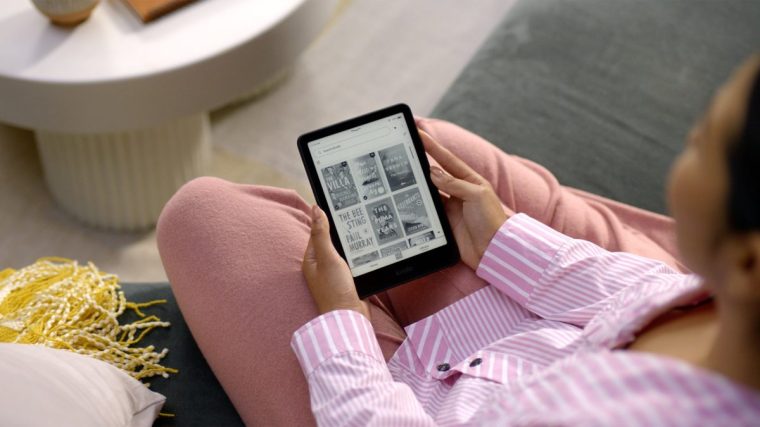

Having clung stubbornly for my whole adult life to good old-fashioned paper and ink, last year I joined the ranks of Kindle owners (a decade or so on, I might add, from my baby-boomer parents). I haven’t looked back. Don’t get me wrong: I still love a “real” book – the smell, the weight, the look of them on the shelves – but the convenience and comfort of the e-reader is undeniable. I can balance it in creative positions, freeing up my hands for cups of tea and glasses of wine; I can download books on the go; and I avoid the eye-rolls of my partner when he discovers that the thousand or so pages I optimistically intend to read on our weekend mini-break have used up half of our easyJet luggage allowance.

I also enjoy Kindle’s interactive features – I look up words frequently and I highlight favourite passages. Of course, it’s possible to do both of these things on paper – but the immediacy of the dictionary on Kindle (you just press down on the word and, provided you’re connected to Wi-Fi, the definition will appear) means I look up words that I otherwise would have skimmed over; that my highlighted quotes are all stored in one place means I’m much more likely to return to them – and hence remember them – than I would have had I underlined them in pencil.

But one thing I hadn’t anticipated was that this useful highlight feature would make reading on Kindle something of a communal experience. Kindle pre-underlines the most popular passages, which have been highlighted and saved by other readers, with a tiny message: “520 other readers highlighted”. And it is with these seemingly inconsequential words that I find myself tangled in a love-hate relationship.

I realise it’s possible to go to settings and turn it off. But I can’t quite bring myself to. What keeps me hooked is not only that you feel you are in some sort of community with these “other readers” – like a much less intimate version of buying a second-hand book and finding someone else’s notes inside – but the slightly murkier feeling that I might miss something if I no longer had access to this information. Hundreds of other people have highlighted this paragraph? Well, that must be the most important bit! And then I can make sure that, even if I don’t highlight it myself, I read it extra-carefully.

Of course, the effect is exponential: the more people who are drawn to it, the more people highlight it, and the more important it seems to everyone else. Which brings me to the hate. Because as much as I feel I have to read it extra carefully lest I miss the crucial point, within the highly personal and intimate experience of reading alone, I also resent that my attention has been drawn to something inorganically.

I am aware that this sounds a little grandiose. (Just turn it off! Or don’t! It’s just a book! Who cares!) But the more I’ve noticed it, the more I’ve realised that it functions in the same way as viral content online – and it rubs me up the wrong way to be offline, reading a book, and still having those same neurons (the overworked mental department of Fomo, Groupthink and Sense of Self) firing. We all know that popularity or virality doesn’t always correspond with quality or importance – but, online, once something has attracted a certain amount of attention, it’s very difficult to avoid it. In the social media era, we are all exposed to ideas and information simply because they matter to other people. So too with Kindle.

And like on Kindle, the effect of this is not always derailing or damaging, as it is when said content is violent and harmful. Sometimes it’s more insidious: an uneventful 20-minute scroll might leave us feeling unmoored from ourselves, forgetful and distractable, our minds suddenly flooded with information about literally hundreds of other lives that in the endless pool of content and the hyperreality of the online space start to blur with our own. A friend said to me she had a brilliant time at Glastonbury but began to doubt herself, almost forgetting her own experience, when she opened Instagram on the train home and saw everyone else’s pictures. I know exactly the feeling she means: it’s not a straightforward fear of missing out, but a dissolving of the boundaries between yourself and everyone else.

This dissolution is also what creates positive, communal experiences online. We are automatically in a club with everyone on the same Subreddit, everyone with the same hashtag in their bio, everyone who has liked the same meme. Content thrives on mass relatability; the more relatable it is, the more traction it picks up and the more eyes it gets on it.

Of course, Kindle differs from content. Books – good books, at least – are not written to go viral. Their words simply become canonised when they speak organically to their readers. That’s what makes art special. It’s also part of what makes the highlight feature so appealing – knowing that other people are out there, reading the same words, having thoughts and feelings about them.

But when words are digitised, even in lovely, tactile e-ink, there is a very fine line between them and content. The simple addition of an underline to a sentence, along with a helpful reminder of how many other people have dwelled on it, is enough to turn it into a meme.

Sometimes I challenge myself: can I read through this popular highlighted passage without lingering over it longer than I have any other? Can I, in other words, still think for myself? As soon as you become aware of it, it’s impossible to say for sure. But as much as I resent my own thoughts becoming inextricable from those of anonymous strangers, I also can’t help but care about what they think. Just in case I’ve missed something.