It is in China’s interest for Russia’s war in Ukraine to continue so America does not turn its full attention to Beijing’s manoeuvres in the Indo-Pacific

Late last year as he was campaigning to return to the White House, Donald Trump said that if elected, he would work hard to “ununite” China and Russia.

Foreign policy experts have dubbed this Trump’s “reverse Nixon strategy”. They are referring to Richard Nixon’s diplomatic coup when he met Chinese leader Mao Zedong, ending over 20 years of hostility with communist China and breaking Beijing’s alliance with Moscow.

Back then, Washington was able to exploit the multiple frictions that had built up in relations between the brotherly communist states and included military clashes over a disputed section of their border in 1969.

Today, the US has no such possibility. Over the past 30 years, China and Russia have built a relationship around common interests that is highly pragmatic, flexible and resilient to shocks. They are united by their determination to reduce Western dominance of international affairs and create what they term a “just” global order based on non-Western norms and values.

This does not mean to say that China and Russia do not have differences. They do, but they are manageable. For example, the Chinese leadership was reportedly unimpressed by Moscow’s decision late last year to deepen relations with North Korea to support its war in Ukraine. Chinese policymakers fear that the signing of a mutual defence treaty by the two countries might complicate Beijing’s relations with Pyongyang.

Like Russia, China sees divisions and weakness in the West, but its instinct is to play the long game and seek evolutionary change in international affairs. By contrast, Moscow is in a hurry, and its approach is revolutionary. It wants to break what remains of Western unity and exploit the emerging chaos to dictate the establishment of a new security architecture in Europe, one that restores an exclusive zone of Russian interest.

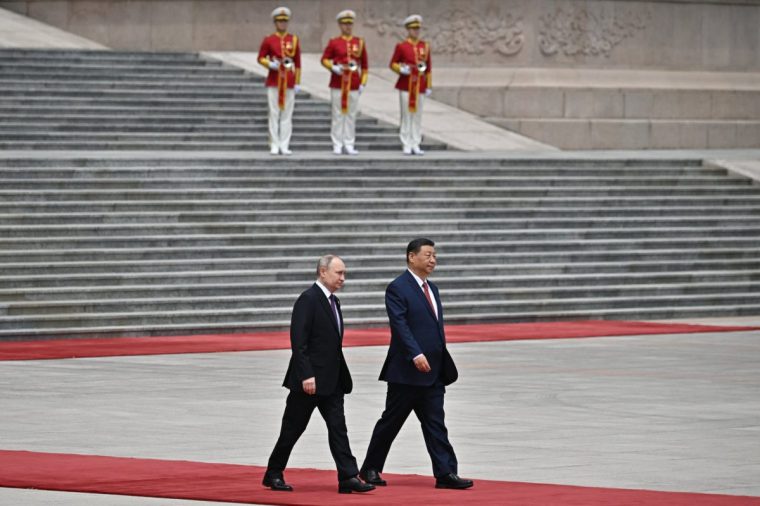

This explains Vladimir Putin’s decision to unleash full-scale war on Ukraine. Despite its stated neutrality in the conflict and a platitudinous “peace plan” drawn up with Brazil, China has stood by Russia’s side and enabled it to continue fighting. Without Chinese support, Russia would have sued for peace long ago.

Not only does China buy about 50 per cent of Russia’s crude oil exports, it also imports Russian gas, providing Moscow with vitally needed income that has been sharply reduced from Western sources because of sanctions and other changes in trade patterns since February 2022.

In addition, China exports dual-use technologies such as machine tools and components that are used in the defence industry to produce weapons. Around 70 per cent of Russia’s machine tool imports come from Russia and about 90 per cent of imported microelectronics.

According to a recent Bloomberg report, 92 per cent of the foreign parts found in Russian drones used against targets in Ukraine originate in China. These include electronics, cameras, engines, antennas and navigations modules. Last week, Ukraine’s GUR defence intelligence agency claimed that it had discovered for the first time a drone made entirely from Chinese components.

Bulldozers delivered from China played a key role in Russia’s ability to build defensive lines in Ukraine in early 2023 that thwarted Kyiv’s counteroffensive in the summer of 2024.

As the Chinese foreign minister told the EU’s foreign policy chief in early July in a rare moment of candour, Beijing cannot afford to see Russia defeated in Ukraine because this would allow the US to focus its full attention on China. This suggests China is comfortable with the war continuing if it does not escalate to dangerous levels.

According to Chinese accounts, in March 2023, Xi Jinping warned Putin against threatening to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. The Russian leader’s nuclear rhetoric had caused considerable alarm in Washington and persuaded the Biden administration that the defeat of Russia’s army in Ukraine would be an undesirable outcome because of the risk of escalation.

However, just as it is impossible to prove that Putin was bluffing, there is no evidence to show that his threats were serious. The Russians have also not admitted that there was Chinese intervention to calm the waters.

A protracted war in Ukraine could indeed satisfy Chinese interests. Even if the Trump administration does not want to pay for Ukraine’s defence, it cannot ignore the war. From a Chinese perspective, US weapons purchased by Europe and delivered to Ukraine are weapons that cannot potentially be used against China in the event of a military clash with the US in the Indo-Pacific.

However, if the war continues into September and Trump acts on his word and introduces secondary sanctions against countries trading with Russia, China might find itself punished for supporting Russia’s war effort.

In its 18th sanctions package, adopted this month, the EU finally blacklisted several Chinese companies suspected of supplying drone technologies to Russia. Chinese banks may now also find themselves in the firing line for helping Russia to evade sanctions.

Despite howls of protest from Beijing, the Chinese leadership knows that neither the US nor Europe is prepared to take substantial punitive action against China over its support for Russia for fear of retaliation.

With Russia so dependent on China, and Beijing not having any motivation to question its partnership with Russia, US hopes of engineering a split between the two are a fantasy.

John Lough is a former Nato representative in Moscow and head of foreign policy at the New Eurasian Strategies Centre, a London-based think-tank